Tetragonula hockingsi

Tetragonula hockingsi (Cockerell, 1929) is a small stingless bee native to Australia. It is found primarily in the Northern Territory and in northern Queensland.[2] The colonies can get quite large, with up to 10,000 workers and a single queen.[3][4] Workers of Tetragonula hockingsi have been observed in fatal fights with other Tetragonula species, where the worker bees risk their lives for the potential benefit of scarce resources.[3]

| Tetragonula hockingsi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lateral view - female worker | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Tribe: | Meliponini |

| Genus: | Tetragonula |

| Species: | T. hockingsi |

| Binomial name | |

| Tetragonula hockingsi Cockerell, 1929 | |

| |

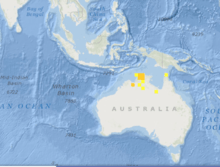

| Range of T. hockingsi [1] | |

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Tetragonula hockingsi is a stingless bee, and thus belongs to the tribe Meliponini, which includes about 500 species. T. hockingsi belongs to the genus Tetragonula. The species is named in honour of Harold J. Hockings, who documented numerous early observations on Australia's stingless bee species, his notes of which were published in 1884.[5]

Reclassification

Tetragonula hockingsi was previously known as Trigona hockingsi, however this species was recently reclassified according to Charles Duncan Michener.[6] In 1961, Brazilian bee expert, Professor J.S. Moure, first proposed the subgenus name Tetragonula.[2] It was an effort to improve the classification system by dividing the huge genus Trigona into subgenera. This classification, supported by Michener's classification, splits Trigona into 9 smaller subgenera.[6] The subgenus Tetragonula includes about 30 other stingless bee species that are found in Oceania, in countries ranging from Australia, Indonesia, New Guinea, Malaysia, Thailand, The Philippines, India, Sri Lanka, and The Solomon Islands.[2]

Description and identification

T. hockingsi is diagnosed by jet black body colour. The side of the thorax is densely and evenly covered with fine, short hair, which distinguishes the species from T. clypearis and T. sapiens. The only distinction in appearance between T. carbonaria is that T. hockingsi is larger.[2]

Identification

The female worker has a typical body length of 4.1-4.5 mm, and an average wing length of 4.4-4.7 mm, including the tegula. The mesopleuron and metapleuron are covered with fine hair. The malar space is also hairy and relatively long, and the mesoscutum does not have distinct glabrous bands.[2]

The male drone has a typical body length of 4.0-4.4 mm, and an average wing length of 4.5-4.7 mm. The male hind tibia is particularly wide and flat, and the last tergum is apically rounded and not beaked.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Distribution

Bees of the genus Trigona are commonly found throughout the tropics.[7] T. hockingsi bees like to nest in hollow dead trees or logs.[8] T. hockingsi is common in northern Australia, particularly throughout parts of Northern Territory and north coastal Queensland.[7]

Nest Structure

In T. hockingsi, the brood cells are shaped in small irregular horizontal combs.[2] This is in contrast to T. carbonaria, where larval cells are constructed along a spiral horizontal comb.[9] Further, the species lacks a projecting, external entrance tunnel.[2] The combs of the nest are extremely important as they provide the substrate on which workers live, food is stored and the brood is reared. Further, the wax itself plays a vital role in the dispersal of pheromones and creates a specific nest odour. T. hockingsi has little, or even no lining of resin and wax at the entrance holes to its nests.[9]

Colony Cycle

All stingless bees of the tribe Meliponini build cells in a brood chamber within the nest; unlike bees of other tribes. They do not reuse these brood cells but constantly build new cells. The brood chamber is surrounded by the involucrum, which is a multilayered envelope. T. hockingsi constructs brood combs during the Provisioning and Ovipositioning Process (POP). First, workers construct a new brood cell and provision the cell with liquid food. Next, the queen lays an egg in the provisioned cell on top of the food. Finally, the workers cap and seal the brood cell, and the POP is complete.[4]

Tetragonula hockingsi has an ancestral approach to its construction of brood cells. They build loose aggregation of cells with a lot of spaces between adjacent cells. The cells are built randomly within the layers, which are horizontal planes of clusters of cells. The brood layers are supported by pillars, which are vertical wax structures; pillars also provide a connector, allowing the movement of bees between layers. Only a small proportion of the workers are involved in cell construction. The median diameter of brood cells for T. hockingsi is 3.35 mm, and the median height is 4.0 mm.[4]

Behaviour

Foraging Patterns

As is typical in stingless bees, individual workers make decisions that affect the foraging patterns of the colony. The decisions are based on the environment and information from the colony, as well as intrinsic factors. T. hockingsi colonies show distinct diurnal patterns of foraging, determined by environmental cues such as resource availability, solar radiation, temperature, and wind speed. The species showed the highest level of pollen collection in the morning. However, resin foraging was stable over time and there were no noticeable peaks of activity.[8]

Kin Selection

Interaction with other species

Predators

The typical predators for T. hockingsi include many of the same predators for other Meliponini species, such as birds, lizards, spiders, and mammals.[11] As with other stingless bee species, they do not have a great defense against predators.

Diet

Tetragonula hockingsi is a generalist species, meaning they can thrive in various environmental conditions by making use of many different resources. As such, they visit a wide variety of plants. The species particularly forages the fruits of the plant species C. torelliana until the resin resource is completely depleted. T. hockingsi exhibits a peak of waste removal and seed dispersal in the morning, which differs from that of related species T. sapiens, which displays peaks in the afternoon. In some studies, high waste removal activity encouraged inexperienced foragers to start foraging. Waste removal activity is important for the dispersal of seeds of C. torelliana, including the unusual seed dispersal syndrome of mellitochory.[8]

Plant Resin

Plant resins are an extremely important resource for T. hockingsi. They are used for everything from nest building to colony defense, and resin availability limits colony size and growth. These resin resources are crucial, especially since their availability is generally unpredictable.[8]

Defence

Small fighting swarms, called skirmishes, are common amongst Tetragonula bees. Sometimes, these skirmishes escalate into far larger battles and can lead to the deaths of hundreds of bees. Intercolony battles in Tetragonula bees can even result in the usurpation of the defeated hive by the winning colony, which then assumes the territory, resources, and nest.[3]

Typically, T. hockingsi colonies invade local T. carbonaria hives. A common strategy is that T. hockingsi workers eject T. carbonaria young adults from the hive, which results in a shorter and less costly fight. The T. hockingsi colony still takes control of the hive entrance, but many fewer bees die in this type of battle. In their victory, the resources gained include pollen, propolis, and honey stores. This significant reward might explain why workers are willing to self-sacrifice in both the attack and defense of a nest.[3]

Evolution of Fatal Fighting

In the fighting swarms between Tetragonula colonies, the attacking hive faces an immense risk of death of its workers. Fatal fighting is not common in nature, and the evolution may be due to the value of the resource exceeding the value of the individual worker’s life. The benefits to each individual in the attacking hive of gaining resources and colony security must outweigh the risks of a substantial loss of workers. It is believed that the fighting swarms between Tetragonula colonies have evolved as a behavioural strategy. Usurpation may have evolved from behaviours such as territorial attacks, nest raiding, nest site location, or reproductive swarming.[3]

Human Importance

Beekeeping

T. hockingsi is a great bee for beekeeping, and beekeepers often keep one colony. It is typical to keep the stingless bees in a log nest, instead of attempting to transfer the colony. Stingless beekeeping in Australia is fairly novel.[12] As of 2013, there were more than 600 commercial hives containing Australian stingless bees of the subgenus Tetragonula.[3]

References

- GBIF Secretariat: GBIF Backbone Taxonomy, 2013-07-01. Accessed via https://www.gbif.org/species/5801043 on 2015-10-10

- Dollin, A., Walker, K. & Heard, T. (2009) "hockingsi" Sugarbag bee (Tetragonula hockingsi) Updated on 12/9/2011 2:27:22 PM Available online: PaDIL - http://www.padil.gov.au

- Cunningham, John P.; Hereward, James P.; Heard, Tim A.; De Barro, Paul J.; West, Stuart A. (2014). "Bees at War: Interspecific Battles and Nest Usurpation in Stingless Bees" (PDF). The American Naturalist. The University of Chicago Press. 184 (6): 777–786. doi:10.1086/678399. eISSN 1537-5323. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 25438177.CS1 maint: date and year (link)ResearchGate Publication 269412794

- Brito, Rute M., et al. "Brood comb construction by the stingless bees Tetragonula hockingsi and Tetragonula carbonaria." Swarm Intelligence 6.2 (2012): 151-176.

- Hockings, Harold J. (1884). "XI. Notes on two Australian species of Trigona. By Harold J. Hockings". Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London. 32 (1): 149–157. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.1884.tb01606.x. ISSN 0035-8894.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Michener, Charles Duncan (2007) [1st pub. 2000]. The bees of the world (2nd ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801885730.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Gardener, Mark C.; Rowe, Richard J.; Gillman, Michael P. (2003-03-01). "Tropical Bees (Trigona hockingsi) Show No Preference for Nectar with Amino Acids". Biotropica. 35 (1): 119–125. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2003.tb00269.x. JSTOR 30043041.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Wallace, Helen M.; Lee, David J. (2010-07-01). "Resin-foraging by colonies of Trigona sapiens and T. hockingsi (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Meliponini) and consequent seed dispersal of Corymbia torelliana (Myrtaceae)" (PDF). Apidologie. 41 (4): 428–435. doi:10.1051/apido/2009074.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Franck, P.; et al. (2004). "Nest architecture and genetic differentiation in a species complex of Australian stingless bees". Molecular Ecology. 13 (8): 2317–2331. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02236.x. eISSN 1365-294X. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 15245404.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Palmer, Kellie A.; Oldroyd, Benjamin P.; Quezada-Euán, José Javier G.; Paxton, Robert J.; May-Itza, William De J. (2002). "Paternity frequency and maternity of males in some stingless bee species". Molecular Ecology. 11 (10): 2107–2113. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01589.x. PMID 12296952.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Hilário, S.D.; Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L. (2003). "Thermal Evidence of the Invasion of a Stingless Bee Nest by a Mammal" (PDF). Brazilian Journal of Biology. 63 (3): 457–462. doi:10.1590/s1519-69842003000300011. PMID 14758704.

- Heard, Tim A.; Dollin, Anne E. (2000). "Stingless bee keeping in Australia: snapshot of an infant industry". Bee World. Taylor & Francis. 81 (3): 116–125. doi:10.1080/0005772x.2000.11099481. ISSN 0005-772X.CS1 maint: date and year (link)ResearchGate Publication 277616572