Tetragonisca angustula

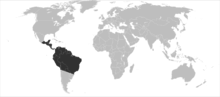

Tetragonisca angustula is a small eusocial stingless bee found in México, Central and South America.[1] It is known by a variety of names in different regions (e.g. jataí, yatei, jaty, virginitas, angelitas inglesas, españolita, mariola, chipisas, virgencitas, and mariolitas). A subspecies, Tetragonisca angustula fiebrigi, occupies different areas in South America and has a slightly different coloration.[2]

| Tetragonisca angustula | |

|---|---|

| A Tetragonisca angustula bee guarding the nest-entrance | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | T. angustula |

| Binomial name | |

| Tetragonisca angustula (Latreille, 1811) | |

| |

| Distribution | |

T. angustula is a very small bee and builds unobtrusive nests, allowing it to thrive in urban areas. It also produces large amounts of honey, and is thus frequently kept in wooden hives by beekeepers. T. angustula hives are often overlooked, and since the bee lacks a stinger, it is not seen as a threat to humans.

Many of their behaviors are concerned with colonizing a new nest and producing offspring, demonstrated by their swarming and nursing behaviors, however a special caste of T. angustula are soldiers who are slightly larger than the workers. The soldiers in a T. angustula nest are very good at protecting the hive against intruders which makes up for not having a stinger.[3] Some of these soldiers hover in mid air outside the nest, which is seen in the adjacent picture.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

T. angustula is a member of the order Hymenoptera, which is one of the four largest insect orders.[4] It is in the family Apidae, subfamily Apinae. Along with other species in the tribe Meliponini, T. angustula is a eusocial stingless bee. There are approximately 500 known species in this tribe, a majority of which are located in the Neotropics.[5] T. angustula has two described two subspecies, T. angustula fiebrigi and T. angustula angustula which have different coloration on their mesepisternum and occupy slightly different regions.[2]

Description and identification

T. angustula is an exceptionally small bee, about 4–5 mm.[6] Along with all other bees in the tribe Meliponini, it is stingless and has a reduced wing venation and penicilla (bristles on the leg).[5] The subspecies T. angustula fiebrigi has a light yellow mesepisternum, while T. angustula angustula has black.[2] Guard bees, which make up about 1–6% of each hive, weigh more than foragers by about 30% and have smaller heads, as well as longer hind legs. Remarkable for the stingless bee clade, T. angustula has a pronounced size dimorphism between the queen and worker castes.[7]

Distribution and habitat

T. angustula has a large habitat distribution across Central and South America. The species has been found as far north as Mexico and south as far as Argentina. It has been labeled "one of the most widespread bee species in the neotropics."[1] The subspecies T. angustula fiebrigi is found more in the southern hemisphere, occupying parts of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and other southern countries. The subspecies T. angustula angustula has a larger presence in Brazil and is found more in the northern hemisphere, occupying Panama, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Nicaragua etc.[2]

T. angustula distribution overlaps with many other stingless bee species, with an especially large correlation with Paratrigona subnuda distribution across Mesoaerica.[1] In the Atlantic rainforest, deforestation for sugar cane plantations is extensive and contributes to the rarity of T. angustula in that area, as well as the stingless bee Melipona scutellaris.

Nests for T. angustula are found in many different settings. Their nests are the predominant bee nests in recovering forest habitats, but are also present in structured forests, depleted forests, and urban settings. Like other stingless bees, T. angustula finds pre-existing cavities, such as holes in tree trunks, cavities in walls, or even abandoned ant or termite nests, for their new nest sites.[1]

Colony cycle

A T. angustula colony will only reproduce once a year, as opposed to many honeybees that can reproduce three or four times in a year. The largest colony cycle occurs during the summer in South America, with most of the new brood hatching between December and March. This time of the year coincides with the best foraging conditions, which ensure enough food can be provided for the larvae. Each colony has one reproductive queen to mate and lay eggs.[8]

Swarming

Colonies are founded by swarming; a young queen and a small fraction of workers leave the mother nest for a new nest site. Before swarming, scout bees explore suitable cavities in the area surrounding the mother nest. This scouting often lasts between two days and two weeks. The new nest sites are within a few hundred meters of the mother nest to allow continued contact with the mother nest, which can last from a week up to six months for T. angustula, which is longer than many other bee species. Resources are transferred from the mother nest to the new nest, including pollen, honey, and cerumen, but the new nest continues to have very small stores compared to the mother nest. Cerumen, which comes from the mother nest, is a wax used to seal cracks and holes in the new nest site.[8]

A swarming colony can have as many as 10,000 bees, but less than 10% relocate to the new nest. Some workers help settle at the new nest site and then return to the mother nest within a few days. The mother colony cannot produce another swarm while the new nest is dependent on it, so once the new nest is settled, connection is severed.[8]

Nest building

_(6788207763).jpg)

Once a nest site is found, the existing cavity must be cleaned. After the pre-existing container is ready to be inhabited, the workers build several horizontal brood combs in the center of the nest. This brood chamber is surrounded by layers of cerumen, called the involucrum, which helps maintain a constant climate in the brood chamber.[8]

Stingless bees add a distinct entrance tube to their nests. This tube is also made of wax and is thought to assist in protection from predators. The tube is on average 2 cm in length and 0.6 cm in diameter and is often closed during the night. Soldier bees are seen guarding this entrance at all hours.[8]

Behavior

Mating

After the nest is cleaned and built, the virgin queen leaves to find a mate. Before she leaves, the queen performs an ‘orientation flight’ to help her find the hive after mating. This flight is a series of circles in the air with the queen’s head facing the entrance to the nest. The virgin queen leaves on her nuptial flight around 7 to 15 days old. In a few cases, queens go out on a second nuptial flight, mating with another male.[9]

Males are thought to come together from many different colonies to form reproductive aggregations composed of hundreds of males, which would provide a queen with the opportunity to compare multiple mates and find the best candidate. Larger aggregations might also be more successful in quickly attracting a queen due to the increased amount of male pheromone present, making the nuptial flight shorter.[10] Queens tend to return to the nest 2–7 days after leaving to start oviposition.[8]

Division of labor

Like many other stingless bee species, T. angustula workers take part in different activities based on their age. The average lifespan of the worker bees is around 21 days, but many live up to about 60 days. The first tasks that worker bees perform include courting the queen (surround her in the hive) and helping with oviposition (see section on nursing). Young bees (1 to about 15 days old) also assist with putting cerumen on brood combs and cleaning the nest. Foraging behavior starts about 16 days after a worker emerges and will continue for the rest of its life. Grooming behavior and resin manipulation are most common in ‘older’ bees, about 20 to 55 days old.[11]

Worker bees perform many actions throughout their lives, and while age divides workers between different tasks, a large overlap of jobs are still being done at one time. Worker bees do not guard the hive, though, since this job is left to soldier bees, which are larger.[11]

While the existence of a soldier caste is well-known in ants and termites, up until 2012 the phenomenon was unknown among bees, when it was discovered that T. angustula has a similar caste of defensive specialists that help guard the nest entrance against intruders.[12] Subsequent research has shown at least 9 other species possess such "soldiers," including T. fiebrigi and Frieseomelitta longipes, with the guards not only larger, but also sometimes a different color from ordinary workers.[13]

Nursing

Nursing behavior, along with oviposition, is known as the provisioning and oviposition process, shortened to “POP”.[14] Before oviposition occurs, workers fill the cells in the hive with food. Once the egg is placed in the cell, it is covered and not tended to again. So, any differences among bees during their initial development must come from differences in the environment within their cells. The size of the cells and the amount of food in each cell is the main determining factor in the size and role of the bee that develops in the cell. Therefore, T. angustula workers fulfill their biggest role before an egg is even placed in a cell.[7]

Workers, males, soldiers, and queens are all morphologically distinct in T. angustula and these differences result from the varied developmental environments found in the cell.[7]

Workers

The average percentage of workers in a T. angustula brood is about 83.6%. While the ratios may change slightly from nest to nest, workers make up the majority of each brood. Their cell size and food allowance is generally seen as the baseline for comparisons since most cells in a nest are for workers.[10]

Soldiers

Of the workers produced, about 1-6% are soldier-sized. Soldiers occupy the cells in the center of the comb and worker bees fill these cells with extra food compared to normal workers. This is an example in which nutritional availability during development impacts larval development.[7]

Males

A trade-off is seen between worker and male production within a brood. Males are produced at higher levels when food availability rises, because they are given more food in their cells, which means that males are often produced in late summer (February to April) when food is plentiful. About 16.3% of a brood consists of males, but this changes depending on the season.[10]

Males do not help around the hive after they have matured, but instead leave the nest to reproduce and never return. The investment in their growth is aimed at the possibility of males passing on their genes (and therefore the queen and worker’s genes) during reproduction with virgin queens from other hives.[10]

Queens

Queens are rare among a brood since only one mated queen is needed for each hive. An estimated 0.2% of a brood is made up of queens and this rate does not vary with the seasons. Queens are raised in the largest cells, known as royal cells, which are built on the edge of a comb.[10]

Communication

T. angustula bees do not have an easily observable form of communication. While they must cooperate in the hive to perform various tasks as a group, many tasks are performed individually. Olfactory cues have been tested in relation to both nestmate recognition[3] and in foraging location,[15] but no strong links could be made. Chemical cues do play a role in foraging activities, with individuals choosing to pollinate plants that have been previously visited by other foragers, but this is an indirect form of communication.[15]

Foraging

Foragers mostly collect nectar, pollen, and plant resin. Foraging activity levels are similar for pollen, nectar and resin foragers: highest activity levels were found around noon.[16] Foraging distances have been estimated to be below 600m, which is relatively short compared to larger bee species.[17]

In many species of stingless bees foragers recruit nestmates to profitable food patches of pollen or nectar.[18] In T. angustula, however, this recruitment is weak.[19] Instead, foragers use chemical cues to locate a good food source as well as visual stimuli remembered from previous foraging trips. Experiments have shown that forager bees will respond to odor priming when put in direct contact with the odor during the experiment, but will not learn the odor if it is simply present in the hive. This shows that T. angustula foragers learn from their own personal experiences but do not pick up information from their fellow foragers. This dependence on personal experience to find food along with the lack of observable group foraging activity labels T. angustula as solitary foragers.[15]

Interaction with other species

Diet

T. angustula bees visit a large number of plants to find food. Stingless bees in general are very important in pollinating 30 to 80% of the plants in their biomes, and T. angustula is one of the most widespread stingless bees in South America. In one study in Brazil, T. angustula bees were seen at 61 different plants, 45 of them being visited by almost exclusively this species of bee. The most important food source for T. angustula is believed to be Schinus terebinthifolius in the Anacardiaceae. Plants from the Asteraceae and Meliaceae were also visited in large numbers. Pollen types from different plants vary in their size and surface texture, which makes T. angustula honey distinct compared to honey with different pollen grains.[20]

Nest defense

.jpg)

The wax tube entrance to each T. angustula hive provides a great advantage in respect to protection against invaders. Between two and 45 soldiers are stationed at this entrance at all times.[6] There are two types of T. angustula soldiers. One type will stand on the tube and detect bees of the same species that do not belong in the hive. The second type will hover near the entrance of the tube and defend against flying intruders that are not T. angustula.[7]

Kin selection

Nestmate recognition

T. angustula guard bees are extremely good at differentiating between foreign individuals. A study in 2011 found that T. angustula is better at nestmate recognition than all other bee species that have been studied to date. They made no errors in recognizing the bees that belonged and never once turned away a nestmate. They were fooled by approximately 8% of non-nestmate bees who sought to enter the hive which is quite low in comparison to other bees.[3]

T. angustula guards are also much better than the average worker bee at recognizing their nestmates at the hive entrance. When they are experimentally put in other contexts away from the hive entrance, recognition errors increase greatly. This demonstrates the importance of individual recognition during specific times, but also shows that T. angustula bees do not generally distinguish between their nestmates and other members of their species. Research is still being conducted on how guards differentiate between bees, but odor of resin seems to have no effect on recognition.[21]

Worker queen conflict

While the queen in a T. angustula hive will lay most of the eggs in a brood, some workers also have the ability to develop and lay eggs. Unlike reproductive eggs, these worker eggs do not have a reticulum and thus develop into males. The worker queen conflict arises over competition to lay eggs in the fixed number of cells in the nest. When the queen produces more eggs, there will be more workers to build more cells, and the workers will be able to lay an egg in the open cells. However the queen lays eggs irregularly throughout the year so the number of cells fluctuates.[14]

The queen will try to lay eggs in as many cells as she can, decreasing the opportunity for workers to lay their eggs. They work fast during oviposition and in some cases will eat the workers’ eggs to make more room for her own. The queen is dominant in this conflict and ends up controlling the availability of oviposition sites.[14]

Human importance

T. angustula are very adept at living in urban settings. They can build their nest in a variety of places, including holes in buildings. More often than not, humans are not even aware of the presence of T. angustula nests and therefore leave them unharmed. This same study showed that bees took refuge inside their nest when humans approached, making them even less conspicuous and decreasing direct contact between human and bee.[22]

Many beekeepers take advantage of T. angustula for its stinglessness and discreetness. Nests are widely traded in Latin America, making T. angustula among the more cultivated species of stingless bees.[10]

Honey

The honey produced by T. angustula is known in some regions as ‘miel de angelita’, which means ‘little-angel honey.’ The honey is said to contain medicinal properties, which has been studied in relation to preventing specific infections. In places like Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador, the price of ‘miel de angelita’ can be as much as ten times more than the price of honey produced by common honey bees.[23]

Composition

Like most honey, T. angustula honey is made up of simple sugars, water, and ash. The specific ratio of these three components makes each honey unique however, and can be affected by season, climate, and other factors that affect flora availability. T. angustula honey contains more moisture than honey from typical honey bees and is also more acidic, giving it a complex flavor.[23]

Antibacterial activity

Honey and propolis, a glue like substance that bees use as sealant, collected by T. angustula have some health benefits for humans. The honey and propolis contain various chemicals that show antibacterial activity towards an infection causing bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus. Honey and propolis gathered from different geographical areas have different chemical compositions yet they all exhibit some type of antibacterial activity. Another bee, Apis mellifera, produces honey and propolis with very similar qualities.[24]

Environmental concerns

Forests are being destroyed all over the world, including the Atlantic Rainforest in Brazil. The Atlantic Rainforest has very high levels of biodiversity but human fragmentation of the forest is leading to huge loss. Due to the interconnectedness of the environment the loss of one plant or insect could cause many others to go extinct. As seen above, T. angustula bees are quite important for pollinating many plants and providing good quality honey. Steps are taken to understand the diet of these bees and their nest sites in order to keep them from dying out in an area. Conservation of the forest is a priority of many scientists and preservationists, and the survival of stingless bees plays a factor in the importance of keeping these forests.[20]

References

- Batista, Milson (2003). "Nesting sites and abundance of Meliponini (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in heterogeneous habitats of the Atlantic Rain Forest, Bahai, Brazil". Lundiana. 4 (1): 19–23.

- Stuchi, Ana Lucia (2012). "Molecular Marker to Identify Two Stingless Bee Species: Tetragonisca angustula and Tetragonisca fiebrigi (Hymenoptera, Meliponinae)". Sociobiology. 59 (1): 123–134. doi:10.13102/sociobiology.v59i1.671.

- Jones, Sam M.; van Zweden, Jelle S.; Grüter, Christoph; Menezes, Cristiano; Alves, Denise A.; Nunes-Silva, Patrícia; Czaczkes, Tomer; Imperatriz-Fonseca, Vera L.; Ratnieks, Francis L. W. (20 September 2011). "The role of wax and resin in the nestmate recognition system of a stingless bee, Tetragonisca angustula". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 66 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1007/s00265-011-1246-7.

- "Hymenoptera". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Costa, Marco A.; Del Lama, Marco A.; Melo, Gabriel A.R.; Sheppard, Walter S. (January 2003). "Molecular phylogeny of the stingless bees (Apidae, Apinae, Meliponini) inferred from mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences". Apidologie. 34 (1): 73–84. doi:10.1051/apido:2002051.

- Wittmann, D. (January 1985). "Aerial defense of the nest by workers of the stingless bee Trigona (Tetragonisca) angustula (Latreille) (Hymenoptera: Apidae)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 16 (2): 111–114. doi:10.1007/BF00295143.

- Segers, Francisca (17 January 2015). "Soldier production in a stingless bee depends on rearing location and nurse behavior". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 69 (4): 613–623. doi:10.1007/s00265-015-1872-6.

- van Veen, J. W.; Sommeijer, M. J. (1 February 2000). "Colony reproduction in Tetragonisca angustula (Apidae, Meliponini)". Insectes Sociaux. 47 (1): 70–75. doi:10.1007/s000400050011.

- Van Veen, Johan Wilhelm; Sommeijer, Marinus Jan (January 2000). "Observations on gynes and drones around nuptial flights in the stingless bees and (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponinae)". Apidologie. 31 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1051/apido:2000105.

- Prato, M; Soares, A E E (31 July 2013). "Production of Sexuals and Mating Frequency in the Stingless Bee Tetragonisca angustula (Latreille) (Hymenoptera, Apidae)". Neotropical Entomology. 42 (5): 474–482. doi:10.1007/s13744-013-0154-0. PMID 23949986.

- Grosso, Adriana (2002). "Labor Division, Average Life Span, Survival Curve, and Nest Architecture of Tetragonisca angustula angustula (Hymenoptera, Apinae, Meliponini)". Sociobiology. 40 (3): 615–637.

- Grüter, C; Menezes, C; Imperatriz-Fonseca, VL; Ratnieks, FL (2012). "A morphologically specialized soldier caste improves colony defense in a neotropical eusocial bee". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109: 1182–1186. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113398109. PMC 3268333. PMID 22232688.

- Grüter, C.; et al. (2017). "Repeated evolution of soldier sub-castes suggests parasitism drives social complexity in stingless bees". Nature Communications. 8. doi:10.1038/s41467-016-0012-y.

- Koedam, D.; Broné, M.; van Tienen, P.G.M. (18 February 2014). "The regulation of worker-oviposition in the stingless bee Trigona (Tetragonisca) angustula Illiger (Apidae, Meliponinae)". Insectes Sociaux. 44 (3): 229–244. doi:10.1007/s000400050044.

- Mc Cabe, S. I.; Farina, W. M. (30 May 2010). "Olfactory learning in the stingless bee Tetragonisca angustula (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponini)". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 196 (7): 481–490. doi:10.1007/s00359-010-0536-2.

- De Bruijn, L.L.M.; Sommeijer, M.J. (1997). "Colony foraging in different species of stingless bees (Apidae, Meliponinae) and the regulation of individual nectar foraging". Insectes Sociaux. 44: 35–47. doi:10.1007/s000400050028.

- Araújo, E.D.; Costa, M.; Chaud-Netto, J.; Fowler, H.G. (2004). "Body size and flight distance in stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Meliponini): Inference of flight range and possible ecological implications". Brazilian Journal of Biology. 64 (3b): 563–568. doi:10.1590/s1519-69842004000400003.

- Lindauer, M.; Kerr, W.E. (1960). "Communication between the workers of stingless bees". Bee World. 41: 29–71. doi:10.1080/0005772x.1960.11095309.

- Aguilar, I.; Fonseca, A.; Biesmeijer, J.C. (2005). "Recruitment and communication of food source location in three species of stingless bees (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponini)". Apidologie. 36 (3): 313–324. doi:10.1051/apido:2005005.

- Braga, JA; Sales, EO; Soares Neto, J; Conde, MM; Barth, OM; Maria, CL (December 2012). "Floral sources to Tetragonisca angustula (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and their pollen morphology in a Southeastern Brazilian Atlantic Forest". Revista de Biología Tropical. 60 (4): 1491–501. doi:10.15517/rbt.v60i4.2067. PMID 23342504.

- Couvillon, M. J.; Segers, F. H. I. D.; Cooper-Bowman, R.; Truslove, G.; Nascimento, D. L.; Nascimento, F. S.; Ratnieks, F. L. W. (25 April 2013). "Context affects nestmate recognition errors in honey bees and stingless bees". Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (16): 3055–3061. doi:10.1242/jeb.085324. PMID 23619413.

- Velez-Ruiz, Rita I.; Gonzalez, Victor H.; Engel, Michael S. (29 July 2013). "Observations on the urban ecology of the Neotropical stingless bee Tetragonisca angustula (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini)". Journal of Melittology. 0 (15): 1. doi:10.17161/jom.v0i15.4528.

- Fuenmayor, Carlos Alberto (2012). "'Miel de Angelita'- nutritional composition and physicochemical properties of Tetragonisca angustula". Interciencia. 37 (2): 142–147.

- Miorin, P.L.; Levy Junior, N.C.; Custodio, A.R.; Bretz, W.A.; Marcucci, M.C. (November 2003). "Antibacterial activity of honey and propolis from Apis mellifera and Tetragonisca angustula against Staphylococcus aureus". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 95 (5): 913–920. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02050.x.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tetragonisca angustula. |