Tectonic evolution of the Barberton greenstone belt

The Barberton greenstone belt (BGB) is located in the Kapvaal craton of southeastern Africa. It characterizes one of the most well-preserved and oldest pieces of continental crust today by containing rocks in the Barberton Granite Greenstone Terrain (3.55–3.22 Ga). The BGB is a small, cusp-shaped succession of volcanic and sedimentary rocks, surrounded on all sides by granitoid plutons which range in age from >3547 to <3225 Ma.[1] It is commonly known as the type locality of the ultramafic, extrusive volcanic rock, the komatiite. Greenstone belts are geologic regions generally composed of mafic to ultramafic volcanic sequences that have undergone metamorphism. These belts are associated with sedimentary rocks that occur within Archean and Proterozoic cratons between granitic bodies. Their name is derived from the green hue that comes from the metamorphic minerals associated with the mafic rocks. These regions are theorized to have formed at ancient oceanic spreading centers and island arcs.[2] In simple terms, greenstone belts are described as metamorphosed volcanic belts. Being one of the few most well-preserved Archean portions of the crust, with Archean felsic volcanic rocks, the BGB is well studied. It provides present geologic evidence of Earth during the Archean (pre-3.0 Ga). Despite the BGB being a well studied area, its tectonic evolution has been the cause of much debate.

General geology of the BGB

The BGB is contained within part of a larger system called the Barberton Granite Greenstone Terrain (BGGT) which includes two main components; the supracrustal succession, which defines the BGB portion, and the deeper-level intrusive units that surround the BGB. Major rock types found within the BGB are mafic to ultramafic volcanics, sedimentary, and shallow intrusive rocks covered by a thin sedimentary veneer. The deeper-level intrusive pluton units dome up under the greenstone belt and are divided into two major groups: the TTG group, (tonalite-trondhjemite-granodiorite) which consists of plagioclase dominant feldspar minerals and the GMS group (granite-monzonite-syenite), in which alkali feldspars are the dominant mineral composition.[3] Pre-3.2 Ga, eruptions of mafic to ultramafic volcanics formed thick sequences. Following the formation of the thick volcanic layers was cyclic deposition of volcanic and sedimentary rocks. Then intrusions of plutonic TTG bodies began the formation of dome-and-keel structures. The volcanic layers deformed into synclines and the dome like TTG bodies created anticlines which is represented in the BGB today.[4]

Stratigraphy

The BGB consists of locally derived sediments and chemical sediments, but is composed mostly of TTGs and greenstones, as briefly discussed above.[5] Three main lithostratigraphic units are used to divide the BGB. The base contains the Onverwacht, followed by the Fig Tree, and the topmost Moodies Groups.[5] The Onverwacht Group is composed largely of mafic and ultramafic volcanics. Thin interbedded sedimentary units that have silicified into impure chert mark breaks that have resulted from eruptive activity. This group ranges in age from >3547 to ~3260 Ma and is over 10 km thick. The Fig Tree Group was deposited between ~3260 and 3225 Ma. It is defined as a transitional unit of interlayered volcanic clasts and land derived sediments that were eroded from the underlying greenstone succession. The Moodies Group, post-3225 Ma, is a combination of sandstone and conglomerate originating from the erosion of the underlying greenstone unit and the uplifted plutonic rocks.[3]

Structure

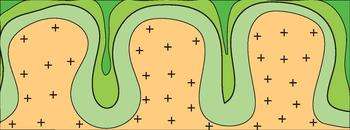

The structural pattern within the region shows a series of anticlines and synclines that plunge towards the core of the belt. Synclines are the dominant folding structure within the region. However, there is a major anticline, called the Onverwacht Anticline, located in the central portion of the BGB.[6] Granite-greenstone terrains are characterized by broad domiform TTG bodies underlying tight synclinal basalts and komatiites. This common structure associated with greenstone belts is called a 'dome-and-keel' structure (shown to the right). The formation of this particular structure is not yet fully understood but there are numerous models that attempt to explain it as well as the overall evolution of the greenstone belt.[7]

Models

The tectonic evolution of the BGB is a common source of controversy within the scientific community. Being a well-preserved piece of old continental crust, the observed kinematics, structures and mineralogy within the BGB have been well studied. Although the area is well studied, the understanding as to how these structures came to be is still uncertain. Numerous models, derived from geologic modeling, have been generated in an attempt to piece together the extensive tectonic evolution of the BGB. The following sections are a limited representation of current models which provide possible explanations for the formation of the BGB.

Accretion

This model functions under the assumption that Archean tectonics were similar to present day plate tectonics. It claims the BGB is a result of multiple events involving a subduction-like environment followed by arc processes causing arc amalgamation. In this setting, terrains converge onto an immobile craton and reflect sequential stacking. This accretion-like convergent process is thought to have occurred ~3.23 Ga.[8] Some interpretations of this model involve the presence of oceanic crust originating from subduction accretion of crust in a collision arc setting.[9] Other interpretations involving accretion present tectonic amalgamation and suturing of pre-existing bodies to form a larger continental block.[3]

Convective overturn

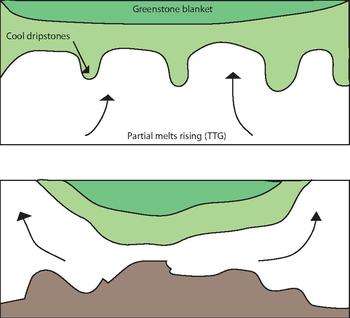

Also called "vertical tectonics" because structures move vertically due to gravity-driven instabilities. The deformation that occurs within the greenstone belts represents a dome-and-keel structure or the rise of diapiric plutons. This model provides an explanation for the dome-and-keel structure associated with greenstone belts. When dense basaltic lavas erupt on top of ductile, less dense TTGs they become weighed down by the overburden and squeeze out from areas with less stress.[7] Partial convective overturn is a related idea stating that a thick, dense, cool greenstone cover in the upper crust acts as an insulator to the underlying hot granitic middle crust. Previously metamorphosed dense amphibolites at the base of the overlying greenstone layer sank down into a partially melted granitic middle crust. These sinking greenstones forced the granitic partial melts sideways and upwards, emplacing them into the margins of the belt and later folding them. The greenstone cover allows the granitic layer to remobilize and form the dome structure. This two stage event is dated between 3.26 and 3.22 Ga.[10]

Importance

The BGB provides an area that contains some of the oldest known rocks available to study. The importance of this geological setting lies in the ability to study and obtain a better understanding of geologic history. Using information from this area has provided direct geologic evidence on the nature and evolution of the Earth before 3.0 Ga. Evidence of early crust, ocean chemistry, biota and atmosphere can be derived from the BGB.[3] Despite the large quantity and the variable explanations of the models, they are necessary to the development of scientific understanding.

References

- de Wit, Maarten J.; Lewis D Ashwal (1997). Greenstone Belts. Clarendon Press.

- "Geology:Greenstone Belts". Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- Lowe, R. David; Gary R. Byerly (2007). "An overview of the geology of the Barberton greenstone belt and vicinity:Implications for early crustal development". Developments in Precambrian Geology. 15.

- Moore, William B.; A. Alexander G. Webb (26 September 2013). "Heat-pipe Earth". Nature. 501: 501–5. Bibcode:2013Natur.501..501M. doi:10.1038/nature12473. PMID 24067709.

- Lowe, David R.; Gary R. Byerly (1999). "Stratigraphy of the west-central part of the Barberton Greenstone Belt, South Africa". Geological Society of America Special Paper. 329.

- Lowe, David R.; Gary R. Byerly (January–February 2007). "Ironstone bodies of the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa: Products of a Cenozoic hydrological system, not Archean hydrothermal vents!". GSA Bulletin. 119: 65–87. doi:10.1130/b25997.1.

- Bedard, Jean H.; Lyal B. Harris; Phillips C. Thurston (2013). "The hunting of the snArc". Precambrian Research. 229: 20–48. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2012.04.001.

- de Ronde, Cornel E.J.; Maarten J. de Wit (August 1994). "Tectonic history of the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa: 490 million years of Archean crustal evolution". Tectonics. 13: 983–1005. Bibcode:1994Tecto..13..983R. doi:10.1029/94tc00353.

- de Wit, M.J.; et al. (1992). "Formation of an Archean continent". Nature. 357 (6379): 553–562. doi:10.1038/357553a0.

- Van Kranendonk, Martin J. (2011). "Cool greenstone drips and the role of partial convective overturn in Barberton greenstone belt evolution". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 60: 346–352. Bibcode:2011JAfES..60..346V. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2011.03.012.