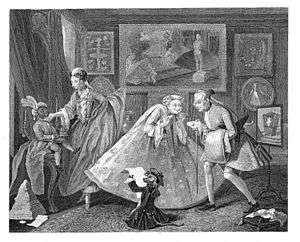

Taste in High Life

Taste in High Life is an oil-on-canvas painting (engraving seen on the right) from around 1742, by William Hogarth.[1] The version seen on the right was engraved by Samuel Phillips in 1798, under commission from John Boydell for a posthumous edition of Hogarth's works, but Phillips's final, third state was not published until 1808.[2]

| Taste in High Life | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | William Hogarth |

| Year | c.1742 |

| Medium | Oil-on-canvas |

| Dimensions | 63 cm × 75 cm (25 in × 30 in) |

Analysis

_by_Joshua_Reynolds.jpg)

The work, a forerunner of Marriage à-la-mode, was intended to satirise and poke fun at the types of dress and garbs that were in fashion at the time, and the superficiality of the tastes and nature of the aristocracy in general. Several figures are seen in the painting, all of whom are dressed in heavily caricatured renditions of the fashion that reigned in the 1740s. Most prominently exhibited is an elderly woman wearing a sacque covered with satirically overblown roses expanded by a large hoop. Standing near her is an opulently dressed man, thought to be "Beau" Colyear, 2nd Earl of Portmore (the dress he wears is said to be the very same he wore to his birthday in the year of the painting's creation)[3] The two huddle together in admiration over the minute porcelain cup held by the lady and saucer held by the lord.[4] Also part of the company is another woman clutching the chin of a black page boy wearing a turban – thought to be designed after Ignatius Sancho, an actor and writer, in his youth[3][5] – both of whom are also dressed as exquisitely as the first two. The black page, holding a type of Chinese porcelain figure, is a servant, and was painted in as an element of irony in the work; as a slave, he mocks his masters, who themselves bowed before fashions and the latest frivolities of upper-class life.[1] Even the monkey standing in the centre foreground wears a flowing, cuffed robe as he examines the list of purchases made by one of the four – it is not known whom – at a recent auction.[3][6] In the painting on the wall, the transitory nature of fashion is represented by the cupids at left, who use a bellows to blow up a fire of discarded petticoats and wigs; at right, the classical form of the female sculpture[7] is contrasted with the cutaway rear view of her enormous hoop underskirt stiffened with whalebone, "the mode 1742" as the painting's legend has it. The fashionable hoops make the seated lady's dress rise up ridiculously behind her, and in a vignette on the fire-screen at right, a lady is shown trapped in a sedan chair that is filled by her hoops—this woman appears again in the background of Hogarth's Beer Street in 1752.

Commissioning

The work was commissioned by Mary Edwards of Kensington,[8] a consistent patron of Hogarth's.[9] Miss Edwards, who had inherited a sum of more than £50,000 pounds a year at the age of twenty-four, was considered eccentric,[6][10] having common lawed married a son of the fourth Duke of Hamilton, Lord Anne Hamilton whom she discarded when he turned out to be profligate. On this occasion she engaged the services of Hogarth with the specific intent of commissioning a painting that would humorously mock what she considered to be the ridiculous fashions and indulgences of the upper class of the time, and "female adornment".[11] It is reported that she did this as an act of vengeance, as she had been ridiculed by the type of people scoffed at in the painting.[12] For a price of sixty guineas, Hogarth agreed to fulfil her request, but it is known that he was not particularly fond of his work; Hogarth often felt less enthusiastic about productions for which a specific commission was made, that were executed to order.[6]

Notes

- "A Taste in High Life — Tate.org". Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- Baumgarten, p.238

- Sala, p.273

- Porter, p.189

- Nichols and Steevens, Hogarth's Works, ii, 158, iii.333, noted in DNB, s.v. "Ignatius Sancho".

- Dobson, p. 82

- Her pose is that of the Venus de' Medici seen from the back, but she wears high-heeled shoes.

- Ritche, p. vi

- She had sat to several portraits and a conversation piece and had purchased Hogarth's Southwark Fair

- Sala, p.270

- Goodman, p.97

- Hogarth, p.37

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taste in High Life. |

- Baumgarten, Linda (2002). What Clothes Reveal. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. ISBN 0-87935-216-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dobson, Austin (2000). William Hogarth. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-8472-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodman, Elise (2001). Art and Culture in the Eighteenth Century. University of Delaware press. ISBN 0-87413-740-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hogarth, William (1833). Anecdotes of William Hogarth. J.B. Nichols and son.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Porter, David (2001). Ideographia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3203-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ritchie, Andrew C. (1968). English Painters, Hogarth to Constable. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-8369-0124-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sala, George Augustus (1986). William Hogarth: Painter, Engraver, and Philosopher. Smith, Elder & co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trusler, John; William Hogarth (1833). The Works of William Hogarth. Jones and co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)