Tarrana

Tarrana (Arabic: الطرانة Aṭ-Ṭarrānah[1], Coptic: ⲧⲉⲣⲉⲛⲟⲩⲑⲓ Terenouthi[2]), known in classical antiquity as Terenuthis, is a town in Monufia Governorate of Egypt. It is located in the western Nile Delta, circa 70 km north-west of Cairo, between the southern prehistoric site of Merimde Beni-salame and the northern town of Kom el-Hisn.[3] The ruins of ancient Terenuthis are found at Kom Abu Billo, northwest of the modern city.

Aṭ-Ṭarrānah الطرانة | |

|---|---|

Town | |

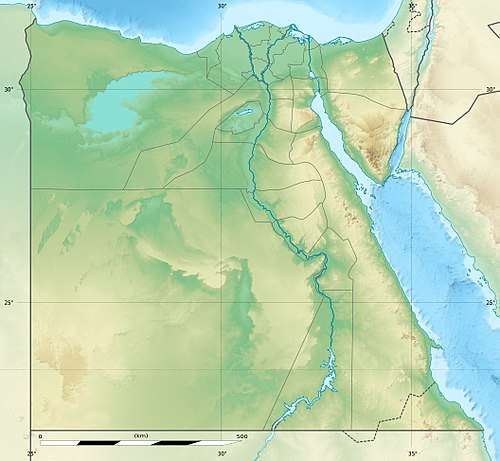

Aṭ-Ṭarrānah Location in Egypt  Aṭ-Ṭarrānah Aṭ-Ṭarrānah (Egypt)  Aṭ-Ṭarrānah Aṭ-Ṭarrānah (Northeast Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 30.43518°N 30.83722°E[1] | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Monufia Governorate |

| Elevation | 12 m (39 ft) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EST) |

Names

Tarrana was known to the ancient Egyptians as Mefket, meaning "turquoise" in Egyptian, itself an epithet of the goddess Hathor who was object of local veneration as "Hathor, Mistress of Turquoises". It was during the Graeco-Roman period that the town became known as Terenuthis,[3] from the Egyptian *Ta-Renenût ("the domain of the goddess Renenutet")[4] which in turn became the Coptic Terenouti, as well as Tarrana or Tarana, the modern town.[3] The toponym Kom Abu Billo (or Kom Abu Bello) refers to a small modern village lying on Terenuthis’ necropolis, in the northwestern part of the whole site; it probably takes the name from the ancient temple of Apollo that once stood here.[3]

Geography

The modern town of El-Tarrana is on the Rosetta branch of the Nile, on the fringes of the Libyan Desert. The ancient necropolis of Kom Abu Billo is a short distance west of El-Tarrana, and is now bisected by the El-Nasseri Canal, a 40-meter-wide irrigation canal.[4]

Excavations

The site was first excavated in 1887-88 by Francis Llewellyn Griffith, who rediscovered the temple of Hathor; then again in 1935 by an expedition organized by the University of Michigan. The most consistent excavation campaign was led by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, and took place between 1969 and 1974 due to the imminent construction of a canal which would have crossed the site.[3] Nowadays, Terenuthis is poorly preserved partly because of these extensive excavations, partly due to the enlargement of the modern city of Tarrana and its crops.[3]

History

The earliest tombs discovered in the site date back to the Old Kingdom, mostly to the 6th Dynasty. Another cemetery was made during the Middle Kingdom, and another one in the New Kingdom, the latter being characterized by the use of large-faced ceramic coffins.[3]

At one point, a temple of Hathor was erected, of which some blocks depicting pharaoh Ptolemy I were found. The temple was accompanied by a dedicated cemetery where sacred cattle were buried. Another temple, dedicated to Apollo, was built at the northernmost border of the site: it was later completely destroyed to its foundations, leaving only a few blocks.[3]

The northeastern sector of the site hosted a very large necropolis dating to the Graeco-Roman and Coptic periods: a large amount of artefacts of various types has been recovered from these tombs, some of which suggests that during these times, Terenuthis flourished thanks to the trade of wine and salt with the Wadi el-Natrun. Many tombs have a square superstructure made from mudbricks, and an inner vaulted roof. From these tombs a large number of stelae were found. These are inscribed with either Greek or Demotic Egyptian texts, and provide glimpses of daily life of the period between 100-300 CE.[3]

A smaller cemetery, dating to the 2nd century CE, was dedicated to Aphrodite. Two Roman thermae once stood south of the aforementioned temple of Apollo.[3]

Terenuthis became a bishopric that, being in the province of Aegyptus Prima was a suffragan of Alexandria and is included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees.[5] Le Quien[6] mentions two of its bishops: Arsinthius in 404; Eulogius at the First Council of Ephesus in 431.

The monks sometimes sought refuge in Terenuthis during incursions of the Maziks.[7] John Moschus went there at the beginning of the 7th century.[8] There is frequent mention of Terenuthis in Christian Coptic literature.

Tarrana was the site of a minor battle during the Muslim conquest of Egypt. After capturing the fortress of Babylon near Cairo in April 641, the Muslim army, led by Amr ibn al-As, moved against the city of Nikiou in the Delta. The Muslims travelled north along with western bank of the Nile, in order to take advantage of the wide-open spaces along the fringes of the Libyan Desert, but had to cross back over to the east to reach Nikiou. Amr chose to cross the Nile at Tarranah, where he was met by a Roman cavalry force. The Muslims easily defeated the Romans and proceeded to reach Nikiou by 13 May.[9]

The name Tarrana dates from around the time of the Mamluk sultan Baibars; the earlier name was Tarnūṭ. It was partially destroyed during the Fatimid conquest of Egypt. Dimashqi spoke praises of it. It was a source of natron.[2]

In December 1293, the emir Baydara, who had assassinated the Mamluk sultan al-Ashraf Khalil and now claimed the title of Sultan for himself, was captured and killed near Tarrana after most of his supporters fled.[10]

Shortly prior to the Battle of Marj Dabiq, members of the qarānīṣa, i.e. veteran mamluks who had belonged to former sultans, were dispatched to fortify numerous localities throughout the Mamluk Sultanate, including Tarrana.[11]

On October 27, 1660,[12]a bloody massacre took place in Tarrana against members of the Faqariya political faction on the orders of the Ottoman governor, who was collaborating with the rival Qasimiya faction.[13] This event was the main source of tension in Egyptian politics for at least 30 years thereafter, with the Faqari leader Ibrahim Bak Dhu al-Faqar vowing to annihilate the Qasimiya in revenge.[13]

The 1885 Census of Egypt recorded Tarrana as a nahiyah under the district of El Negaila in Beheira Governorate; at that time, the population of the town was 1,331 (693 men and 638 women).[14]

Gallery

- The necropolis at Kom Abu Billo

.jpg) Ptolemy I (right) offering to Hathor; block from the temple of Hathor

Ptolemy I (right) offering to Hathor; block from the temple of Hathor- Tomb-chapel, Graeco–Roman period

- Vault of a Graeco–Roman tomb

- Roman funerary stele, Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum

See also

- List of ancient Egyptian sites, including sites of temples

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terenuthis. |

- "Geonames.org. Aṭ-Ṭarrānah". Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Maspero, Jean; Wiet, Gaston (1919). Matériaux pour servir à la géographie de l'Égypte. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. pp. 58, 120–121.

- Hawass, Zahi, Kom Abu Bello, in Bard, Kathryn A. (ed.), "Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt". Routledge, London & New York, 1999, ISBN 0-203-98283-5, pp. 498–500

- McCleary, Roger V. (1992). Johnson, Johnson (ed.). "Ancestor Cults at Terenouthis in Lower Egypt: A Case for Greco-Egyptian Oecumenism". Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization (51): 221–231. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 987

- Oriens christianus, II, 611.

- Cotelier, "Ecclesiæ græcæ monumenta", I, 393.

- Pratum spirituale, LIV, CXIV.

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 1473828651. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- Clifford, Winslow Williams (2013). State Formation and the Structure of Politics in Mamluk Syro-Egypt, 648-741 A.H./1250-1340 C.E. V&R Unipress. pp. 153–54. ISBN 3847100912. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- Ayalon, David (1954). "Studies on the Structure of the Mamluk Army--III". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 16 (1): 79. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00143484. JSTOR 608909.

- Winter, Michael (1992). Egyptian Society Under Ottoman Rule: 1517–1798. London: Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 0-203-16923-9. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Ayalon, David (1960). "Studies in al-Jabartī I. Notes on the Transformation of Mamluk Society in Egypt under the Ottomans". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 3 (3): 307. doi:10.2307/3596053. JSTOR 3596053.

- Egypt min. of finance, census dept (1885). Recensement général de l'Égypte. p. 304. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

Site and blog of the French Archaeological Mission: https://kab.huma-num.fr/ and https://aboubillou.hypotheses.org/ .

- Attribution

- Georgii Cyprii Descriptio orb. rom., ed. Heinrich Gelzer, 125;

- AMÉLINEAU, La géog. de l'Egypte a l'époque Copte (Paris, 1893), 493.