Target market

A target market is a group of customers within a business's serviceable available market at which a business aims its marketing efforts and resources. A target market is a subset of the total market for a product or service.

The target market typically consists of consumers who exhibit similar characteristics (such as age, location, income or lifestyle) and are considered most likely to buy a business's market offerings or are likely to be the most profitable segments for the business to service.

Once the target market(s) have been identified, the business will normally tailor the marketing mix (4 Ps) with the needs and expectations of the target in mind. This may involve carrying out additional consumer research in order to gain deep insights into the typical consumer's motivations, purchasing habits and media usage patterns.

The choice of a suitable target market is one of the final steps in the market segmentation process. The choice of a target market relies heavily on the marketer's judgement, after carrying out basic research to identify those segments with the greatest potential for the business.

Occasionally a business may select more than one segment as the focus of its activities, in which case, it would normally identify a primary target and a secondary target. Primary target markets are those market segments to which marketing efforts are primarily directed and where more of the business's resources are allocated, while secondary markets are often smaller segments or less vital to a product's success.

Selecting the "right" target market is a complex and difficult decision. However, a number of heuristics have been developed to assist with making this decision.

Definition

A target market is a group of customers (individuals, households or organisations), for which an organisation designs, implements and maintains a marketing mix suitable for the needs and preferences of that group.[1]

Target marketing goes against the grain of mass marketing. It involves identifying and selecting specific segments for special attention.[2] Targeting, or the selection of a target market, is just one of the many decisions made by marketers and business analysts during the segmentation process.

Examples of target markets used in practice include:[3]

- Rolls-Royce (motor vehicles): wealthy individuals who are looking for the ultimate in prestige and luxury

- Dooney and Bourke handbags: teenage girls and young women under 35 years

Background

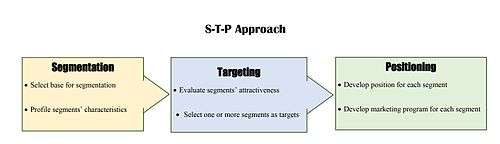

Selection of a target market (or target markets) is part of the overall process known as S-T-P (Segmentation→Targeting→Positioning). Before a business can develop a positioning strategy, it must first segment the market and identify the target (or targets) for the positioning strategy. This allows the business to tailor its marketing activities with the needs, wants, aspirations and expectations of target customers in mind.[4] This enables the business to use its marketing resources more efficiently, resulting in more cost and time efficient marketing efforts. It allows for a richer understanding of customers and therefore enables the creation of marketing strategies and tactics, such as product design, pricing and promotion, that will connect with customers' hearts and minds. Also, targeting makes it possible to collect more precise data about customer needs and behaviors and then analyze that information over time in order to refine market strategies effectively.[5]

The first step in the S-T-P process is market segmentation. In this phase of the planning process, the business identifies the market potential or the total available market (TAM). This is the total number of existing customers plus potential customers, and may also include important influencers. For example, the potential market or TAM for feminine sanitary products might be defined as all women aged 14–50 years. Given that this is a very broad market in terms of both its demographic composition and its needs, this market can be segmented to ascertain whether internal groups with different product needs can be identified. In other words, the market is looking for market-based opportunities that are a good match its current product offerings or whether new product/service offerings need to be devised for specific segments within the overall market.

Market segmentation

Markets generally fall into two broad types, namely consumer markets and business markets. A consumer market consists of individuals or households who purchase goods for private consumption and do not intend to resell those goods for a profit. A business market consists of individuals or organisations who purchase goods for one of three main purposes; (a) for resale; (b) for use in producing other goods or services and; (c) for general use in daily business operations.[6] Approaches to segmentation will vary depending on whether the total available market (TAM) is a consumer market or a business market.

Market segmentation is the process of dividing a total available market, using one of a number of key bases for segmenting such as demographic, geographic, psychographic, behavioural or needs-based segments. For example, a demographic segmentation of the adult male population might yield the segments, Men 18-24; Men 25-39, Men 40-59 and Men 60+. Whereas a psychographic segmentation might yield segments such as Young Singles, Traditional Families, Socially Awares and Conservatives. Identifying consumer demand and opportunity within these segments should assist the marketer to identify the most profitable segments.

Although there are many different ways to segment a market, the most common bases used in practice are:[7]

- Geographic – Residential address, location, climate, region.

- Demographic/socioeconomic segmentation – Gender, age, income, occupation, socio-economic status, educational-level, family status, marital status, ethnic group, religious affiliation.

- Psychographic – Attitudes, values, beliefs, interests and lifestyles.

- Behavioral – usage occasion, degree of loyalty, user status, purchase-readiness[8]

- Needs-based segmentation – relationship between the customer's needs for specific features and product or service benefits[9]

During the market segmentation process, the marketing analyst will have developed detailed profiles for each segment formed. This profile typically describes the similarities between consumers within each segment and the differences between consumers across each of the segments. The primary use of the segment profile is to assess the extent to which a firm's offerings meet the needs of different segments. A profile will include all such information as is relevant for the product or service and may include basic demographic descriptors, purchasing habits, disposition to spend, benefits-sought, brand preferences, loyalty behavior, usage frequency and any other information deemed relevant to the subject at hand.[10]

The segment profile assists in the decision-making process and has a number of specific benefits:[10]

- assists to determine those segments that are most attractive to the business

- provides quantitative data about segments for a more objective assessment of segment attractiveness

- assists in tailoring the product or service offering to the needs of various segments

- provides basic information to assist with targeting

- allocating the firm's resources effectively

After profiling all the market segments formed during the segmentation process, detailed market analysis is carried out to identify one or more segments that are worthy of further investigation. Additional research may be undertaken at this juncture to ascertain which segments require detailed analysis with the potential to become target segments.

Selecting the target market

A key consideration in selecting the target markets is whether customer needs are sufficiently different to warrant segmentation and targeting. In the event that customer needs across the entire market are relatively similar, then the business may decide to use an undifferentiated approach. On the other hand, when customer needs are different across segments, then a differentiated (i.e. targeted) approach is warranted. In certain circumstances, the segmentation analysis may reveal that none of the segments offer genuine opportunities and the firm may decide not to enter the market.[11]

When a marketer enters more than one market, the segments are often labeled the primary target market and the secondary target market. The primary market is the target market selected as the main focus of marketing activities and most of the firm's resources are allocated to the primary target. The secondary target market is likely to be a segment that is not as large as the primary market, but may have growth potential. Alternatively, the secondary target group might consist of a small number of purchasers that account for a relatively high proportion of sales volume perhaps due to purchase value, purchase frequency or loyalty.[12]

In terms of evaluating markets, three core considerations are essential:[13]

- Segment size and growth

- Segment structural attractiveness

- Compatibility with company objectives and resources.

However, these considerations are somewhat subjective and call for high levels of managerial judgement. Accordingly, analysts have turned to more objective measures of segment attractiveness. Historically a number of different approaches have been used to select target markets. These include:[14]

- Distance Criterion: Under this approach, the business attempts to define the primary geographic catchment area for the business by identifying people who live within a predetermined distance of the business. For a retailer or service-provider the distance might be around 5 km; for domestic tourist destination, the distance might be 300km. This method is used extensively in retailing.

- Sales Criterion: Using this method, the business allocates its resources to target markets based on historical sales patterns. This method is especially useful when used in conjunction with sales conversion rates. This method is used in retail. A disadvantage of the method is that it assumes past sales will remain constant and fails to account for incremental market potential.

- Interest Survey Methods: This method is used to identify new business potential. Primary research, typically in the form of surveys, identifies people who have not purchased a product or service, but have positive attitudes and exhibit some interest in making a purchase in the short-term. Although this method overcomes some of the disadvantages of other methods, it is expensive even when syndicated research is used.

- Chain ratio and indexing methods: This method is used in marketing of branded goods and retail. It involves ranking alternative market segments based on current indices. Widely used indices are the Category Index and Brand Index. The Category Index measures overall patterns within the product category while the Brand Index calculates a given brand's performance within the category. By dividing the Category Index by the Brand Index, a measure of market potential can be obtained.

International segmentation and targeting

Segmentation and targeting for international markets is a critical success factor in international expansion. Yet, the diversity of foreign markets in terms of their market attractiveness and risk profile, complicates the process of selecting which markets to enter and which consumers to target. Targeting decisions in international markets have an additional layer of complexity.

An established stream of literature focussing on International Market Segmentation (IMS) suggests that international segmentation and targeting decisions employ a two-stage process:[15]

- 1. Macro-segmentation (assess countries for market attractiveness, i.e. market size, market potential)

- 2. Micro-segmentation (i.e. consumer-level based on personal values and social values)

Analysis carried out in the first stage focuses involves the collection of comparative information about different countries with a view to identifying the most valuable markets to enter. This is facilitated by the relatively wide data availability for macro-variables. Most government departments collect business census data as well as data for a broad range of economic and social indicators that can be used to gauge the attractiveness of various destinations.

Positioning

Positioning is the final step in the S-T-P planning approach (Segmentation→ Targeting → Positioning).[16] Positioning refers to decisions about how to present the offer in a way that resonates with the target market. During the research and analysis carried out during the segmentation and targeting process, the marketer will have gained insights into what motivates consumers to purchase a product or brand. These insights can be used to inform the development of the positioning strategy.

Firms typically develop a detailed positioning statement which includes the target market definition, the market need, the product name and category, the key benefit delivered and the basis of the product's differentiation from any competing alternatives. The communications strategy is the primary means by which businesses communicate their positioning statement to target audiences.[17]

Marketing mix (4 Ps)

Once the segmentation has been carried out, target markets selected and the positioning strategy developed, the marketer can begin to shape the marketing mix (or marketing program) around the needs, wants and motivations of the target audience.[18] The traditional marketing mix refers to four broad levels of marketing decision, namely: product, price, promotion, and place.[19] When implemented successfully, these activities should deliver a firm's products or services to target consumers in a cost efficient manner. The four core marketing activities include: product, price, place and promotion.[20]

The marketing mix is the combination of all of the factors at the command of a marketing manager to satisfy the target market.[21] The elements of the marketing mix are: Product – the item or service that is being offered, through its features and consumer benefits and how it is positioned within the marketplace whether it be a high or low quality product. Price, is a reference to the sacrifices made by a consumer to acquire a product and may include both monetary and psychological costs such as the combination of the ticket price, payment methods and other associated acquisition costs. Place refers to the way that a product physically reaches the consumer – where the service or item is sold; it also includes the distribution channels in which the company uses to get products or services to market. Finally, Promotion refers to marketing communications used to convey the offer to consumers and may include; personal selling, advertising, public and customer relations, sales promotion and any other activities to communicate with target markets.[22]

The first reference to the term, the 'marketing mix' was claimed to be in around 1950 by Neil H. Borden.[23][24] Borden first used the term, 'marketing mix' in an address given while he was the President of the American Marketing Association in the early 1950s. For instance, he is known to have used the term 'marketing mix' in his presidential address given to the American Marketing Association in 1953.[25] However, at that stage, theorists and academics were not in agreement as to what elements made up the so-called marketing mix. Instead, they relied on checklists or lengthy classifications of factors that needed to be considered to understand consumer responses.[26] It wasn't until 1960 when E. Jerome McCarthy published his now-classic work, Basic Marketing: A Managerial Approach that the discipline accepted the 4 Ps as constituting the core elements of the marketing mix.[27] In the 1980s, the 4 Ps was modified and expanded for use in the marketing of services, which were believed to possess unique characteristics which necessitated a different marketing program. The commonly accepted 7Ps of services marketing include: the original four Ps of product, price, place, promotion plus participants (people), physical evidence and process.[28]

Product

A ‘Product’ is "something or anything that can be offered to the customers for attention, acquisition, or consumption and satisfies some want or need." (Riaz & Tanveer (n.d); Goi (2011) and Muala & Qurneh (2012)). The product is the primary means of demonstrating how a company differentiates itself from competitive market offerings. The differences can include quality, reputation, product benefits, product features, brand name or packaging.

Price

Price provides customers with an objective measure of value.(Virvilaite et al., 2009; Nakhleh, 2012). Price can be an important signal of product quality. Prices can also attract specific market segments. For instance, premium pricing is used when a more affluent segment is the target, but a lower-priced strategy might be used when price-conscious consumers are the target. Price can also be used tactically, as a means to advertise, short stints of lower prices increase sales for a variety of reasons such as to shift product over-runs or out of season goods.

Place

Place refers to the availability of the product to the targeted customers (Riaz & Tanveer, n.d). So a product or company doesn't have to be close to where its customer base is but instead they just have to make their product as available as possible. For maximum efficiency, distribution channels must identify where the target market are most likely to make purchases or access the product. Distribution (or place) may also need to consider the needs of special-interest segments such as the elderly or those who are confined to wheelchairs. For instance, businesses may need to provide ramps for wheelchair access or baby change rooms for mothers.

Promotion

Promotion refers to "the marketing communication used to make the offer known to potential customers and persuade them to investigate it further".[29] May comprise elements such as: advertising, PR, direct marketing and sales promotion. Target marketing allows the marketer or sales team to customize their message to the targeted group of consumers in a focused manner. Research has shown that racial similarity, role congruence, labeling intensity of ethnic identification, shared knowledge and ethnic salience all promote positive effects on the target market. Research has generally shown that target marketing strategies are constructed from consumer inferences of similarities between some aspects of the advertisement (e.g., source pictured, language used, lifestyle represented) and characteristics of the consumer (e.g. reality or desire of having the represented style). Consumers are persuaded by the characteristics in the advertisement and those of the consumer.[30]

Strategies for segmenting and targeting

Marketers have outlined five basic strategies to the segmentation and the identification of target markets: undifferentiated marketing or mass marketing, differentiated marketing, concentrated marketing (niche marketing) and micromarketing (hyper-segmentation).

Mass marketing (undifferentiated marketing)

Undifferentiated marketing/Mass marketing is a method which is used to target as many people as possible to advertise one message that marketers want the target market to know (Ramya & Subasakthi). When television first came out, undifferentiated marketing was used in almost all commercial campaigns to spread one message across to a mass of people. The types of commercials that played on the television back then would often be similar to one another that would often try to make the viewers laugh, These same commercials would play on air for multiple weeks/months to target as many viewers as possible which is one of the positive aspects of undifferentiated marketing. However, there are also negative aspects to mass marketing as not everyone thinks the same so it would be extremely difficult to get the same message across to a huge number of people (Ramya & Subasakthi).

Differentiated marketing strategy

Differentiated marketing is a practice in which different messages are advertised to appeal to certain groups of people within the target market (Ramya & Subasakthi). Differentiated marketing however is a method which requires a lot of money to pull off. Due to messages being changed each time to advertise different messages it is extremely expensive to do as it would cost every time to promote a different message. Differentiated marketing also requires a lot time and energy as it takes time to come up with ideas and presentation to market the many different messages, it also requires a lot of resources to use this method. But investing all the time, money and resources into differentiated marketing can be worth it if done correctly, as the different messages can successfully reach the targeted group of people and successfully motivate the targeted group of people to follow the messages that are being advertised (Ramya & Subasakthi).

Concentrated marketing or niche marketing

Niche marketing is a term used in business that focuses on selling its products and services solely on a specific target market. Despite being attractive for small businesses, niche marketing is highly considered to be a difficult marketing strategy as businesses may need thorough and in-depth research to reach its specific target market in order to succeed.[31]

According to (Caragher, 2008),[32] niche marketing is when a firm/ company focuses on a particular aspect or group of consumers to deliver their product and marketing to. Niche marketing, is also primarily known as concentrated marketing, which means that firms are using all their resources and skills on one particular niche. Niche marketing has become one of the most successful marketing strategies for many firms as it identifies key resources and gives the marketer a specific category to focus on and present information to. This allows companies to have a competitive advantage over other larger firms targeting the same group; as a result, it generates higher profit margins. Smaller firms usually implement this method, so that they are able to concentrate on one particular aspect and give full priority to that segment, which helps them compete with larger firms.[32]

Some specialities of niche marketing help the marketing team determine marketing programs and provide clear and specific establishments for marketing plans and goal setting. According to, (Hamlin, Knight and Cuthbert, 2015),[33] niche marketing is usually when firms react to an existing situation.

There are different ways for firms to identify their niche market, but the most common method applied for finding out a niche is by using a marketing audit. This is where a firm evaluates multiple internal and external factors. Factors applied in the audit identify the company's weaknesses and strengths, company's current client base and current marketing techniques. This would then help determine which marketing approach would best fit their niche.

There are 5 key aspects or steps, which are required to achieve successful niche marketing. 1: develop a marketing plan; 2: focus your marketing program; 3: niche to compete against larger firms; 4: niche based upon expertise; 5: develop niches through mergers.[32]

Develop A Marketing Plan:

Developing a market plan is when a firms marketing team evaluates the firms current condition, what niches the company would want to target and any potential competition. A market plan can consist of elements such as, target market, consumer interests, and resources; it must be specific and key to that group of consumers as that is the speciality of niche marketing.[32]

Focus Your Marketing Program:

Focusing your marketing program is when employees are using marketing tools and skills to best of their abilities to maximise market awareness for the company. Niche marketing is not only used for remaining at a competitive advantage in the industry but is also used as a way to attract more consumers and enlarge their client database. By using these tools and skills the company is then able to implement their strategy consistently.[32]

Niche To Compete Against Larger Firms:

Smaller and medium-sized firms are able to compete against niche marketing, as they are able to focus on one primary niche, which really helps the niche to grow. Smaller firms can focus on finding out their clients problems within their niche and can then provide different marketing to appeal to consumer interest.[32]

Niche Based Upon Expertise:

When new companies are formed, different people bring different forms of experience to the company. This is another form of niche marketing, known as niche based on expertise, where someone with a lot of experience in a specific niche may continue market for that niche as they know that niche will produce positive results for the company.[32]

Developing Niches Through Mergers:

A company may have found their potential niche but are unable to market their product/ service across to the niche. This is where merging industry specialist are utilised. As one company may have the tools and skills to market to the niche and the other may have the skills to gather all the necessary information required to conduct this marketing. According to (Caragher, 2008),[32] niche marketing, if done effectively, can be a very powerful concept.[32]

Overall, niche marketing is a great marketing strategy for firms, mainly small and medium-sized firms, as it is a specific and straightforward marketing approach. Once a firm's niche is identified, a team or marketers can then apply relevant marketing to satisfy that niche's wants and demands.[32]

Niche marketing also closely interlinks with direct marketing as direct marketing can easily be implemented on niches within target markets for a more effective marketing approach.

Direct marketing

Direct marketing is a method which firms are able to market directly to their customers needs and wants, it focuses on consumer spending habits and their potential interests. Firms use direct marketing a communication channel to interact and reach out to their existing consumers (Asllani & Halstead, 2015). Direct marketing is done by collecting consumer data through various means. An example is the internet and social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat. Those were a few online methods of which organisations gather their data to know what their consumers like and want allowing organisations to cater to what their target markets wants and their interest (Lund & Marinova, 2014). This method of marketing is becoming increasingly popular as the data allows organisations to come up with more effective promotional strategies and come up with better customize promotional offers that are more accurate to what the customers like, it will also allows organisations to uses their resources more effectively and efficiently and improve customer management relationships. An important tool that organisations use in direct marketing is the RFM model (recency-frequency-monetary value) (Asllani & Halstead, 2015). Despite all the benefits this method can bring, it can be extremely costly which means organisation with low budget constraints would have trouble using this method of marketing..

Online targeting

Digital communications have allowed marketers to segment markets at ever tighter levels - right down to the individual consumer.[34] This process is known as micromarketing, cyber-segmentation or hyper-segmentation. In effect, this allows to the marketer to pursue both a differentiated marketing strategy and a niche marketing strategy to reach the smallest groups in the marketplace.[35] R

Hyper-segmentation relies on extensive information technology, big databases, computerized and flexible manufacturing systems, and integrated distribution systems. Data is captured from electronic communications devices, mapped and logged with a management information system. This enables the integration of observed behaviour (domains accessed) with motives (content involvement), geographics (IP addresses), demographics (self-reported registration details) and brand preferences (site-loyalty, site stickiness). Additional data inputs might include behavioural variables such as frequency (site visits), diversity including visitation across different landscapes and fluidity spanning multiple time periods. Programmed business intelligence software analyses this data and in the process, may also source data inputs from other internal information networks.[36] Marketers and advertisers can then use an inventory of stock images and phrases to compile customised promotion offers in real-time which are delivered to prospective purchasers with a strong interest in the product, or who are in an advanced state of buyer-readiness.[37]

With increased availability of electronic scanner data there has been a greater focus on research of micromarketing and pricing problems that retailers encounter. Research in 1995 by Stephen J. Hoch et al. provided empirical evidence for the micromarketing concept. In 1997, Alan Montgomery used hierarchical Bayes models to improve the estimation procedures of price elasticities, showing that micromarketing strategies can increase gross profits.[38]

With the advent of social media, advertising has become a more efficient at reaching relatively small target audiences.[37] People are constantly exposed to advertisements and their content, which is key to its success. In the past, advertisers had tried to build brand names with television and magazines; however, advertisers have been using audience targeting as a new form of medium.[39] The rise of internet users and its wide availability has made this possible for advertisers.[37] Targeting specific audiences has allowed for advertisers to constantly change the content of the advertisements to fit the needs and interests of the individual viewer. The content of different advertisements are presented to each consumer to fit their individual needs.[40]

The first forms of online advertising targeting came with the implementation of the personal email message.[41] The implementation of the internet in the 1990s had created a new advertising medium;[42] until marketers realized that the internet was a multibillion-dollar industry, most advertising was limited or illicit.[43]

Many argue that the largest disadvantage to this new age of advertising is lack of privacy and the lack of transparency between the consumer and the marketers.[44] Much of the information collected is used without the knowledge of the consumer or their consent.[44] Those who oppose online targeting are worried that personal information will be leaked online such as their personal finances, health records, and personal identification information.[44]

Advertisers use three basic steps in order to target a specific audience: data collection, data analysis, and implementation.[37] They use these steps to accurately gather information from different internet users. The data they collect includes information such as the internet user's age, gender, race, and many other contributing factors.[40] Digital communications has given rise to new methods of targeting:[37]

- Addressable advertising

- Behavioral targeting

- Location-based targeting

- Reverse segmentation (a segment-building approach rather than a segmentation approach)

These methods rely on data collected from consumer-browsing histories and as such, rely on observed behaviour rather than self-reported behaviours. The implication is that data collected is much more reliable, but at the same time attracts concerns about consumer privacy. Many internet users are unaware of the amount of information being taken from them as they browse the internet. They don't know how it is being collected and what it is being used for. Cookies are used, along with other online tracking systems, in order to monitor the internet behaviors of consumers.[45]

Many of these implemented methods have proven to be extremely effective.[46] This has been beneficial for all three parties involved: the advertiser, the producer of the good or service, and the consumer.[37] Those who are opposed of targeting in online advertising are still doubtful of its productivity, often arguing the lack of privacy given to internet users.[47] Many regulations have been in place to combat this issue throughout the United States.[48]

See also

References

- Pride, W.M., Hughes, R.J., Kapoor, J.R., Foundations of Business, Cengage Learning, 2012, p. 311; Williams, C., McWilliams, A. and Lawrence. R., MKTG, 3rd Asia Pacific edition, Cengage Australia, 2017, p.90

- Verma, H.G., Services Marketing:Text and Cases, Delhi, Pearson, 1008, p. 219

- Pride, W.M., Hughes, R.J., Kapoor, J.R., Foundations of Business, Cengage Learning, 2012, p. 311

- Sherlock, Tracie (25 November 2014). "3 Keys to Identifying Your Target Audience". Database: Business Source Complete. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Chapman, Devenish, Dhall, Norris (2011). Business Studies in Action. Milton, QLD Australia: John Wiley & Sons Australia Ltd. pp. 190–196.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pride, W. M. and Ferrell, O.C., Marketing, Mason, OH, Cengage, 2010, p. 160

- Wedel, Michel; Kamakura, Wagner A. (2000). Market Segmentation - Springer. International Series in Quantitative Marketing. 8. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4651-1. ISBN 978-1-4613-7104-5.

- Percy, Rossiter, Elliott (2001). "Target Audience Considerations, in Strategic Advertising Management 2001". Target Audience Considerations. Strategic Advertising Management. Retrieved 23 March 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cohen, A. W, The Marketing Plan. John Wiley & Sons, 2005

- Pride, W. M. and Ferrell, O.C., Marketing, Mason, OH, Cengage, 2010, p. 174

- Pride, W. M. and Ferrell, O.C., Marketing, Mason, OH, Cengage, 2010, p. 176

- Applbaum, K., The Marketing Era: From Professional Practice to Global Provisioning, Routledge, 2004, p. 33-35

- Marketing Insider, "Evaluating Market Segments", Online: http://targetmarketsegmentation.com/target-market/secondary-target-markets/

- Perdue, R., "Target Market Selection and Marketing Strategy: The Colorado Downill Ski Industry", Journal of Travel Research, Spring, 1996, pp 39-46

- Gaston-Breton, Charlotte; Martín Martín, Oscar (2011). "International market selection and segmentation: a two‐stage model". International Marketing Review. 28 (3): 267–290. doi:10.1108/02651331111132857.

- Strydom, J., Introduction to Marketing, Juta and Company, 2005, p. 77

- Rossiter, J. and Percy, L., Advertising Communications and Promotion Management, N.Y., McGraw-Hill, 1997, p. 159

- Kotler, P., Marketing Management (Millennium Edition), Custom Edition for University of Phoenix, Prentice Hall, 2000, p. 9

- McCarthy, Jerome E. (1964). Basic Marketing. A Managerial Approach. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

- "What Is Marketing Mix?". smallbusiness.chron.com. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- Everyday Finance: Economics, Personal Money Management, and Entrepreneurship. Overview: Marketing Mix: Product, Price, Place, Promotion. Everyday Finance: Economics, Personal Money Management, and Entrepreneurship. January 1, 2008. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017.

- Michael R. Czinkota; Ilkka A. Ronkainen (June 25, 2013). International Marketing. Cengage Learning. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-133-62751-7.

- N.H. Borden (1964). "The Concept of the Marketing Mix". Journal of Advertising Research: 2–7.

- N.H. Borden (2001), "The Concept of the Marketing Mix", in M.J. Baker (ed.), Marketing: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management, 5, Routledge, pp. 3–4,

Borden credits his colleague, James Culliton, with the concept of marketers as 'mixers of ingredients' which inspired him to coin the phrase, 'marketing mix'. However, Borden claims credit for the term and certainly contributed to the process of popularising the concept. Culliton, J. The Management of Marketing Costs, [Research Bulletin] Harvard University, 1948

- Dominici, G., "From Marketing Mix to E-Marketing Mix: A Literature Review," International Journal of Business and Management, vol. 9, no. 4. 2009, pp 17-24

- W. Waterschoo; C. van den Bulte (1992). "The 4P Classification of the Marketing Mix Revisited". Journal of Marketing. 56 (4): 83–93. doi:10.1177/002224299205600407. JSTOR 1251988.

- Hunt, Shelby D. and Goolsby, Jerry, "The Rise and Fall of the Functional Approach to Marketing: A Paradigm Displacement Perspective," in Historical Perspectives in Marketing: Essays in Honour of Stanley Hollander, Terence Nevett and Ronald Fullerton (eds), Lexington, MA, Lexington Books, pp 35-51, sdh.ba.ttu.edu/Rise%20and%20Fall%20(88).pdf

- Grönroos, Christian. "From Marketing Mix to Relationship Marketing: Towards a Paradigm Shift in Marketing," Management Decision, vol. 32, no.2, 1994, pp 4-20.

- Blythe, Jim (2009). Key Concepts in Marketing. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Aaker, J., Brumbaugh, A., & Grier, S, & Dick Trickle, "Nontarget Markets and Viewer Distinctiveness: The Impact of Target Marketing on Advertising." Journal of Consumer Psychology (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), Vol. 9, no. 3, 2000, p. 127

- "Niche Marketing Strategy". smallbusiness.chron.com. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- Caragher, Jean Marie (2008). "Expand Your Horizons: Niche Marketing Success Stories". Journal of Accountancy. ProQuest 206796610.

- Hamlin, Robert (2015). "Niche Marketing And Farm Diversification Processes: Insights From New Zealand And Canada". Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems. ProQuest 1757741033.

- Tedlow, R.A. and Jones, G., The Rise and Fall of Mass Marketing, Routledge, N.Y., 1993 Chapter 2

- Kara, A.; Kaynak, E. (1997). "Markets of a Single Customer: Exploiting Conceptual Developments in Market Segmentation". European Journal of Marketing. 31 (11/12): 873–885. doi:10.1108/03090569710190587.

- Louvieris, P., Driver, J. 2001. New Frontiers in Cybersegmentation: Marketing Success in Cyberspace Depends in IP address. Qualitative Market Research. 4. (3). pp. 169-181.

- Cole, Agatha (2012). "Internet Advertising After Sorrell V. IMS Health: A Discussion on Data Privacy & the First Amendment". Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal. 30 (2): 283–316.

- Weitz, Barton and Robin Wensley. Handbook of Marketing, SAGE 2002.

- Draganska, Michaela; Hartmann, Wesely R; Stanglein, Gena (October 2014). "Internet Versus Television Advertising: A Brand-Building Comparison". Journal of Marketing Research. 15 (5): 578–590. doi:10.1509/jmr.13.0124.

- Jansen, Bernard J; Moore, Kathleen; Carmen, Stephen (2013). "Evaluating the Performance of Demographic Targeting Using Gender in Sponsored Search". Information Processing & Management. 49: 286–302. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2012.06.001.

- Seabrook, Andrea (May 30, 2008). "At 30, Spam Going Nowhere Soon". NPR. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Hairong, Li (March 2011). "The Interactive Web". Journal of Advertising Research. 51: 13–34. doi:10.2501/JAR-51-1-013-026. See p. 14.

- "Coalition for Networked Information Information Policies: A Compilation of Position Statements, Principles, Statutes, and Other Pertinent Statements". old.cni.org. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 2013-08-24.

- "The Battle for Online Behavioral Advertising Regulation and Legislation: A Contemporary History". Conference Papers -- International Communication Association. 1: 1–29. 2011.

- Learmonth, Michael (2009-07-13). "Tracking Makes Life Easier for Consumers". Advertising Age. 80 (25): 3–25.

- Guillaume, Johnson D; Greir, Sonya A (2011). "Targeting without Alienating: Multicultural Advertising and the Subtleties of Targeted Advertising". International Journal of Advertising. 2 (30): 233–258.

- Sheehan, Kim Bartel; Gleason, Timothy W (Spring 2001). "Online Privacy: Internet Advertising Practitioners' Knowledge and Practices". Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising. 23 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1080/10641734.2001.10505112.

- Learmonth, Michael (2011-04-04). "Fact vs. fiction: Truth about regulation and online-ad biz". Advertising Age. 82 (14): C6–C7.