Tampa Police Department

The Tampa Police Department (TPD) provides crime prevention and public safety services for the city of Tampa, Florida. The Tampa Police Department has over 1000 authorized sworn law enforcement personnel positions and more than 350 civilian and support staff personnel positions. The current chief of police is Brian Dugan.

| Tampa Police Department | |

|---|---|

MASCOTTE | |

| Common name | Tampa Police Department |

| Abbreviation | TPD |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1855 |

| Preceding agencies | |

| Employees | 1,206 (2020) |

| Annual budget | $163 million (2020)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Florida, United States |

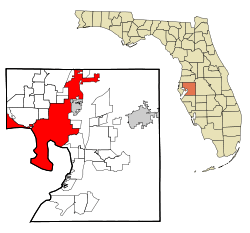

| |

| Tampa Police's jurisdiction. | |

| Population | 392,905 (2018) |

| Legal jurisdiction | Tampa, FL |

| Operational structure | |

| Chief responsible |

|

| Website | |

| www | |

Uniformed officers are deployed on a four days on, four days off work cycle, with an average of twelve officers per squad

History

In 1855 the first official law enforcement position created was City Marshal by an act to incorporate the City of Tampa. Over the next 18 years the City Marshall's duties and responsibilities were expanded to include summoning members of patrol by midnight along with examining and recording marks and brands on butchered cattle.

In 1886, the first police force was created in Tampa by passage of another city ordinance and thus began the Tampa Police Department some fifty-one years after the first police force in America was created. Tampa's first police force was quite small, with a Chief of Police replacing the City Marshall, aided by an Assistant Chief, a Sergeant and three mounted officers. But some key elements of a modern police force were instituted during that time. Standards for officer qualification were established based on merit and physical fitness and officers began wearing uniforms. Two detective positions were also added during this period of time. The following year, on July 15, 1887, the town of Tampa officially incorporated as a city.

Over the next 26 years the Tampa Police Department evolved through a number of reorganizations, adding and subtracting positions, establishing a pension plan for officers and developing rules and regulations dealing with officer's conduct. In 1913 the department created its first Identification Officer position. The officer assigned to the position used the Bertillion System of identification, which preceded the fingerprint method used today in law enforcement. The Bertillion System used a process of measuring body parts such as the nose, eyes and hands along with other characteristics to identify individuals.

1915 was a landmark year as the department relocated to its new headquarters located at Florida Avenue and Jackson Street in Downtown Tampa. That same year Tampa saw the advent of a revolutionary tool in local law enforcement, the automobile. Tampa added an officer to the motored assignment who was both chauffeur and mechanic for the department. In 1936, with automotive thefts rising, the department added an Auto Theft Bureau to deal with this relatively new dilemma. Additional functions such as parking meter enforcement were added to the tasks performed by the department along with an expanded role in traffic law enforcement.

During the years from 1936 to 1961, the department underwent additional redeployments and Tampa saw its first parking meters in the 1940s.

Major developments in the department's history occurred in 1961. First and foremost was a move to a new police building on Tampa Street at Henderson Avenue. This facility would serve as headquarters until the department moved to its current building in 1997. The first floor of the two-story complex housed police operations while the second floor housed the city's jail and administrative operations. A college training program was instituted that year with participating officers being given special consideration pertaining to work hours and finances. The "platoon" deployment system was adopted giving equal numbers of officers to each platoon, which was rotated between day, evening and midnight shifts. The Police Athletic League was officially organized and one officer was assigned to it full-time to provide special activities for Tampa's youth.

In 1962 the Criminal Intelligence Unit was organized and became responsible for developing and disseminating available information to officers through special files and investigations. The Field Instructor system of training newly appointed police officers was established in 1965. Initially, the Field Instructors were the corporals of the squads. Later they were each squad's top performing and senior officers.

1967 brought a new deployment of manpower with the abolition of the platoon system. A flexible deployment system with 21 squads replaced it. The system deployed officers to areas based on need. The Tampa Police academy received certification as a qualified training institute in 1968 by the State Minimum Standards Training Commission. At that time the academy was held inside the police department's building.

1969 brought another revolutionary advent of law enforcement to the department with the purchase of two Hughes 300 helicopters to complement the two fixed-wing aircraft already in operation. The helicopter's role in supporting officers on the ground during searches was tremendous.

The office of Public Information was created in 1971 to act as a liaison between the department and the news media. Also that year, the first Hazardous Device Technician was trained in handling explosives at the US Army Redstone Arsenal base in Huntsville, Alabama. That technician worked alone until 1973 when several other officers were also trained at Redstone.

In 1972 the prisoner booking function, still conducted in the police headquarters building, was transferred to Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office personnel. Sheriff's Office personnel performed the duty at police headquarters until 1979 when the operation was moved to the county jail on Morgan Street at Scott Street.

During 1974, the department established the Internal Affairs Unit to investigate citizen complaints about officers or employees of the department with impartiality and objectivity.

In September 1975, the department embarked on a new era in community relations and crime prevention by creating the School Resource Officer program. The program placed officers into middle and high school level institutes to handle problems that occur and present preventative programs to the students and faculty. The full-time position of police legal advisor was also created that year. One of the most popular programs among officers was implemented in 1975 as well. The take-home car program allowed officers to drive their units to and from work. The philosophies were to reduce maintenance on the cars, eliminate staggered reporting times, free space being used for lockers and promote safety through higher visibility of units in the neighborhoods the officers lived.

1977 saw the creation of the Tactical Response Team or TRT. The team, known in some cities as SWAT, was designed for response to special threat situations requiring special tactics to reduce the threat to officers, subjects and the community.

The Hostage Negotiation Team was formed in 1979 and combined with the Tactical Response Team. Another innovation of modern law enforcement came to Tampa in 1980. The Neighborhood Watch Program was a result of a more nationwide emphasis being placed on crime prevention through public awareness.

In 1981 the Field Instructor program was replaced with the Field Training and Evaluation Program for officer training. The program was innovative at the time of its inception. Special training squads were created with officers assigned to them receiving additional instruction in methods of training new officers. Recruits, fresh out of the academy, were assigned to these squads and received daily training and evaluation for a period of four months before being attached to regular squads.

The same year the department created the Special Anti-Crime Squad or SAC. The unit would later be called the Street Anti-Crime Squad. The unit's function was to address street level and special crime problems within the city. Special Purpose Vehicles or SPVS were added to the department's cadre of mobility that year also. The vehicles, somewhat similar in design to golf carts, were employed to allow the accessibility of foot patrol to the public but not limit the officer's mobility as foot patrol can. Although the program was initially a trial, it later was adopted and units assigned to the downtown area used them effectively.

In 1982 the department formed its first K-9 unit with five dogs and handlers. Four of the five were trained in search and track while the fifth dog was trained in both narcotic and explosives detection. The police Dive Team was organized that same year in August. They provided the capability for underwater search and recovery to the department on a twenty-four-hour basis.

In 1983 the department conducted an experiment in deployment of personnel. District I used a quad system and District II used a sector system. The object was to provide better supervision, establish clear chains of command and promote the neighborhood policing concept. By 1984, both districts adopted the sector system.

Later in 1983 the department's Communication Section underwent a colossal transformation. The days of calls being handwritten by call takers were over for good at the Tampa Police Department. A new million dollar plus computer aided dispatch system or C.A.D. replaced the old method and drastically improved the way calls were transferred to dispatch and response by street units.

In response to the increased amount of street level narcotics dealers in Tampa, a unit was developed to address the problem. The Q.U.A.D. Squads were the answer to the question. Living up to their name, which stands for Quick Uniformed Attack on Drugs, in late 1989 the city was divided up into four quadrants and these four squads set to work defending the streets of Tampa against the onslaught of drug dealers and buyers.

In 1993, the department implemented the Mobile Dispatch System or MDS. The system allowed computers to be placed in police cars for direct dispatch without tying up the radio airwaves. Officers were now capable of running registration and wanted persons checks without communicating to a dispatcher. 1996 saw the creation of a new patrol district with the addition of District III. A new Mounted Unit for horse patrol was created to address the rising need in congestion during special events and the Ybor City entertainment district of Tampa. Another major addition was the Firehouse COP program that placed officers working firehouse areas using community oriented policing philosophies. The officers would respond to neighborhood problems as their primary responsibility and build relationships with the residents to better understand and address their needs.

A major change occurred in 1997 when the Tampa Police Department moved to its new headquarters located at Franklin Street and Madison Street across from city hall. That location also had historical significance in that the original courthouse had stood on the same location. Another development enjoyed by officers was the reinstatement of the take home car program, which had been abolished nearly ten years earlier.

In 1998 the transition to decentralization took another large step with officers from district II moving into their new station in North Tampa near Busch Gardens. Groundbreaking on the District I station began the same year.

District I occupied its new 15,000-square-foot (1,400 m2) facility in 1999. That year the department's helicopters were equipped with GyroCam camera systems that allowed video downlinking and recording. This new age technology offered more advance surveillance and officer safety capabilities to the department.

The Sexual Predator Identification and Notification program was also instituted in 1999 to comply with the Florida Sexual Predator Act. The program monitors these offenders and tracks them using a sophisticated computer database and is administered by Firehouse officers.

The decentralization of the Tampa Police Department reached its culmination in the year 2000 with the relocation of the communications section to its new state-of-the-art facility in East Tampa. In February 2004 The department conducted a full re-deployment and divided the city into three districts. Each district was equipped with squads to address street-level narcotics, prostitution and other target crimes.

West Tampa Police Department

In 1895, West Tampa was an independently incorporated city that operated its own police department. It saw the loss of one officer in its short history. On July 18, 1920, Patrolman Juan Nales and another officer were walking a man they arrested to jail when the suspect attacked.[2] The suspect gained control of Nales's gun and fatally shot him. The suspect was captured after fleeing and subsequently convicted of murder.[3] In 1925, West Tampa was annexed by Tampa and the West Tampa Police Department was absorbed by the Tampa Police Department.[4]

District system

District one

The District One Patrol Division serves Tampa's peninsula, west side, and Davis Islands areas, including Tampa International Airport, Raymond James Stadium, Hyde Park, Courtney Campbell Causeway and Bayshore Boulevard. There are twelve uniformed squads in the district.

District two

The District Two Patrol Division serves Tampa's northern portion, including Busch Gardens, Sulphur Springs and the Tampa Palms and Hunters Green area frequently referred to as "New Tampa." There are fourteen uniformed squads in the district.

District three

The District Three Patrol Division serves East Tampa, the Ybor City area and the Port of Tampa, including Downtown Tampa. There are twelve uniformed squads in the district.

District specialist units

District Latent Investigation Squads

A squad of plainclothes detectives, the District Latent Investigation Squad is assigned to each district for latent investigation of crimes against property occurring in the area encompassed by the district. Part of the squad is also charged with conducting latent investigations on assaults.

Quick Uniformed Attack on Drugs Squads

Each district utilizes Q.U.A.D. (Quick Uniformed Attack on Drugs) Squads to aggressively work toward the reduction of open street drug dealing within the city. Implemented in February 1989, the unit's mission includes the investigation of all street level narcotics related offenses; the investigation of street level narcotics violations with the assistance of the residents in the affected community; gathering and dissemination of pertinent street level narcotic intelligence to other divisions; and direct access for citizens to Q.U.A.D. officers assigned to their community. The squads conduct frequent initiatives to remove visible street drug dealers from neighborhoods. Q.U.A.D. was merged with SAC in 2009 to form Rapid Offender Control (R.O.C.) squads in each district.

Street Anti-Crime Squads

The Street Anti-Crime (SAC) squads assigned to each district are plainclothes units that work in each district to reduce prostitution and prostitution related crimes, as well as robbery, burglary and auto theft related crimes. SAC was merged with Q.U.A.D. in 2009 to form Rapid Offender Control (R.O.C.) squads in each district.

Crime Prevention Practitioners

A police officer, and a Crime Prevention Practitioner, formerly known as a Community Service Officer are deployed to each district to act in a proactive approach to crime prevention. The team addresses complaints, along with evaluating needs in the communities within each district. They also function as the liaison in each district for the Neighborhood Watch Program. They develop and oversee Neighborhood Watch groups that are partnerships between the community and police department, composed of volunteer citizens, working together to reduce crime.

Ranks and insignia

| Title | Insignia[5] |

|---|---|

| Chief of Police | |

| Assistant Chief of Police | |

| Deputy Chief | |

| Major | |

| Captain | |

| Lieutenant | |

| Sergeant | |

| Corporal | |

| Master Police Officer | |

| Police Officer | No insignia |

City marshal

M. L. Shanahan (1859)

Chief of Police

- James G. Littleton (1967–1974)

- Charles Otero (1974–1979)

- Clayton Briggs (1979-1981)

- Robert Smith (1981–1985)

- Don Newburger (1985–1987)

- A.C. McLane (1987–1992)

- Eduardo Gonzalez (1992–1993)

- Bennie Holder (1993–2003)

- Stephen Hogue (2003–2009)

- Jane Castor (2009–2015)

- Eric Ward (2015–2017)

- Brian Dugan (2017–present)

Fallen officers

Since 1895 there have been 31 Tampa Police Officers killed in the line of duty.

Since the first recorded Police death in 1792, there have been more than 17,000 Law Enforcement Officers killed in the line of duty. The National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington D.C. bears the names of more than 14,000 federal, state, and local Law Enforcement Officers who have been killed in the line of duty.

On average, one Police Officer is killed in the line of duty every 53 hours. More than 56,000 law enforcement officers are assaulted each year, resulting in over 16,000 injuries annually.

Roll Call of Honor

- Officer David Curtis– June 29, 2010

- Officer Jeffery Kocab– June 29, 2010

- Corporal Michael Roberts– August 19, 2009

- Detective Juan Serrano– February 25, 2006

- Master Police Officer Lois Marrero– July 6, 2001

- Detective Randy Bell– May 19, 1998

- Detective Ricky Childers– May 19, 1998

- Officer Norris Epps, Jr.– January 18, 1995

- Officer Porfirio Soto, Jr.– December 30, 1988

- Sergeant Gary S. Pricher– November 4, 1983

- Detective Gerald A. Rauft– July 24, 1981

- Officer Anthony W. Williams– November 3, 1975

- Sergeant Richard Lee Cloud– October 23, 1975

- Detective Kenneth D. Berlin, Jr.– September 27, 1975

- Corporal John R. Collier– December 5, 1970

- Officer William D. Krikava– January 1, 1965

- Officer Rolla L. Standau– November 29, 1963

- Officer Carl F. Chastain– February 12, 1958

- Officer Morris D. Lopez– July 9, 1949

- Officer Richard S. Booth– November 28, 1943

- Detective Lester H. Henley– April 11, 1941

- Vice Chief Arthur L. Berry– January 31, 1941

- Detective Joe Nance– October 1, 1939

- Officer Bryan A. Reese– August 29, 1935

- Detective Thomas M. Chevis– April 7, 1938

- Officer Henry R. Lett– September 24, 1922

- Patrolman Juan Nales– July 18, 1920

- Officer James Ronco– May 27, 1916

- Marshal Joseph Walker– September 15, 1915

- Captain Samuel J. Carter– June 2, 1905

- Officer John (Jack) McCormick– September 26, 1895

Collusion with the KKK

On November 30, 1935, six members of the Modern Democrats[6], a local Socialist affiliated political party, were arrested by Tampa Police in a warrant-less raid on one of their meetings and taken to the station. None of them were charged with any crime, however, three of them, Joseph Shoemaker, Eugene Poulnot, and Sam Rogers, were kidnapped by masked Klansmen as they left the police station. They were taken to a wooded area near the Tampa suburb of Brandon where they were flogged and burned with hot tar. Shoemaker died nine days later as a result of his injuries.

The Hillsborough County Sheriff in cooperation with the state attorney mounted an investigation, eventually concluding that the attack was orchestrated by city employees and the Tampa Police. Five of the seven officers who raided the Modern Democrats meeting, and one other officer, were charged with the murder of Joseph Shoemaker, kidnapping, assault, and the attempted murder of Eugene Poulnot and Sam Rogers. As the investigation continued, evidence surfaced indicating the involvement of the Ku Klux Klan. Shoemaker's brother had received threats from the Klan by phone, and known Klan leaders had been seen at police headquarters shortly before the kidnappings. Three more people, reputed Klansmen, were arrested and charged in the incident, and Tampa Police Chief, R.G. Tittsworth, as well as a police department stenographer, were charged as accessories after the fact. Eleven people, all connected with either Tampa Police Department or the KKK, were charged in connection to the kidnappings and murder.[7]

See also

- List of U.S. state and local law enforcement agencies

- Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office

References

- Sullivan, Carl; Baranauckas, Carla (June 26, 2020). "Here's how much money goes to police departments in largest cities across the U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020.

- "Patrolman Juan Nales".

- "Fallen Patrolman - Juan Nales". 14 July 2014.

- West_Tampa#Annexation

- "Tampa Police Department (Florida) /". www.uniforminsignia.org. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Ingalls, Robert (1977). "The Tampa Flogging Case, Urban Vigilantism". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 56 (1): 13–27. JSTOR 30149824.

- Urban Vigilantes in the New South: Tampa, 1882-1936 By Robert P. Ingalls ISBN 978-0813012230