Talbiya

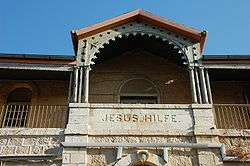

Talbiya or Talbiyeh (Arabic: الطالبية, Hebrew: טלביה), officially Komemiyut, is an upscale neighborhood in Jerusalem, Israel, between Rehavia and Katamon. It was built in the 1920s and 1930s on land purchased from the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Most of the early residents were affluent Middle Eastern Christians who built elegant homes with Renaissance, Moorish and Arab architectural motifs, surrounded by trees and flowering gardens.[1]

History

After World War I, Constantine Salameh, a native of Beirut, bought land in Talbiya from the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate with the idea of building a prestigious neighborhood for Middle Eastern Christians. In addition to a villa for himself, Salameh built two apartment houses on the square that was named for him.[2] After the 1948 Palestine war many Arab residents of Talbiya including Salameh lost the right to their properties due to Israel's Absentee Property Law. Salameh sought to regain his property under a clause that distinguished between persons who left Israeli territory due to the conflict and those who were absent for other reasons, but after being convinced that the High Court would not rule in his favor for fear of creating a precedent he accepted a symbolic $700,000 in compensation for all of his multimillion-dollar properties located in Israel.[2] Talbiya's Gan Hashoshanim (Rose Garden) dates back to the 1930s. After the establishment of the State of Israel, official Independence Day events were held at this park.

Before the Six-Day War, many of the villas in Talbiya housed foreign consulates. The home of Constantine Salameh, which he leased to the Belgian consulate, faces a flowering square, originally Salameh Square, later renamed Wingate Square to commemorate Orde Wingate, a British officer who trained members of the Haganah in the 1930s. Marcus Street is named for Colonel David (Mickey) Marcus, an officer in the U.S. army who volunteered to be a military advisor in Israel's War of Independence.[1]

Today

The neighborhood's Hebrew name Komemiyut, (קוממיות) introduced as a hebraization after the establishment of the state, never caught on, and it is still known as Talbiya.[3] Some of Jerusalem's important cultural institutions are located in Talbiya, among them the Jerusalem Theater, the Van Leer Institute and Beit HaNassi, the official residence of the President of Israel.

The Lands Problem

Some lands in Talbiya are owned by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. In August 2016 a group of investors, which was called "Nayot Komemiyut Investments", purchased 500 dunams from the Patriarch, while a part of it was in Talbiya.[4] Formerly, the lands had been leased by the Jewish National Fund (JNF) and were subleased to Israeli tenants who registered their leasehold rights in the Land registration in Israel, but the revenue was not paid to the Patriarch by the JNF. It was one of the reasons of selling the lands by the Patriarch to "Nayot Komemiyut", which committed to collect the rents for the Patriarch, as it was stated in a verdict of the Jerusalem District Court.[5]

Selling the areas to a third hand aside the Patriarchate of Jerusalem and the JNF, puts the Israeli tenants, which most of them are elderly, under an economic uncertainty, while their real estate's value goes down. Tenants cannot design plans of TAMA 38[6] The investors are also unable to construct or widen the buildings, because the land is still hired by the JNF for several decades. The tenants requested the Israeli government to nationalize the leased lands, or at least to compensate them in real terms for their acquires, which were equal to real estate values. The Patriarchate reacted by claiming that its property rights were offended. In the beginning of 2018, Jerusalem Municipality joined the Israeli Government and refused to release the lands overwhelmingly, claiming it had to evaluate every leased estate for its betterment levy.[7] As a result, the Christian leaders closed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to visitors during the end of February 2018.[8]

Notable residents

- Haim Yavin

- Edward Said

- Reuven Rivlin

- Ya'akov Ne'eman

- Martin Buber

- David Friedman

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Talbiya. |

- Eylon, Lili (2011). "Jerusalem: Architecture in the British Mandate Period". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- "Villa Dolorosa: The story of Villa Salameh, one of the most impressive buildings in Jerusalem, is a tale of a passion for beauty and luxury, of Palestinian emigration and loss, and of a titanic battle for its ownership". Haaretz. 8 January 2003. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Ofer Aderet (29 July 2011). "A stir over sign language: A recently discovered trove of documents from the 1950s reveals a nasty battle in Jerusalem over the hebraization of street and neighborhood names. This campaign is still raging today". Haaretz. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- Sue Surkes (30 July 2017). "Church land sales to anonymous buyers set homeowners on edge". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

Nir Hasson (7 September 2017). "JNF blasts 'Greedy' Investors who bought Jerusalem Land from Greek Orthodox Church: Jewish National Fund pays 1 million shekels to investment company to settle lease dispute, but questions who actually owns the land in three upscale neighborhoods". Haaretz. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

Nir Hasson (14 October 2017). "Greek Orthodox Church quietly selling off Israeli Assets at Fire Sale Prices: A neighborhood in Jerusalem was sold for just a few million dollars, with the identity of the buyer kept secret". Haaretz. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

Shlomit Tsur (14 March 2018). "Church real estate sale rocks Jerusalem housing market: In some prestigious Jerusalem neighborhoods prices have fallen 30% in the 18 months since the deal due to uncertainty about JNF leases". Globes. Retrieved 14 July 2018. - Judge Moshe Ravid, Land Assessor Moshe Yitzhaki and Lawyer Dr. Lior Davidai (20 May 2013). "Verdict given by the Jerusalem District Court" (PDF). Alex Shapira & Co., Law Firm (in Hebrew). Retrieved 14 July 2018.

To act exclusively in the name of the Patriarch from the date of signing this agreement with any third party, including the JNF, which is related to the lease agreements, and subject to the provisions of this agreement, to do in its name and place any action which the Patriarch is entitled to make, in connection with the lease agreements, and without derogating from the generality of the aforesaid, collect and receive annual lease fees and/or any lease fees due to the Patriarch in accordance with the lease agreements, to collect any debt of any kind towards the Patriarch in respect of past periods with respect to the lands included in the lease agreements, including debts in respect of leasing fees and/or compensation for breach of lease agreements made in the past or to be made in the future.

- Aryeh Deverett (21 March 2016). "What is TAMA 38?". Bizness Magazine. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

TAMA 38 is a unique Israeli construction program created to strengthen and upgrade older apartment buildings. It serves to protect them from earthquakes and to increase urban housing units in high demand areas.

- "Betterment Levies". The World Bank. 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

World Watch Monitor (16 February 2018). "Jerusalem church leaders object to municipal tax levy". World Watch Monitor. Retrieved 14 July 2018. - Raf Sanchez (25 February 2018). "Christian leaders shut Jerusalem's Church of Holy Sepulchre in protest at Israel imposing taxes". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

Udi Shaham and Lahav Harkov (25 February 2018). "Church of the Holy Sepulchre closes over municipality's tax demands". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

Gregg Montgomery (26 February 2018). "Church officials: Holy Sepulchre to remain closed over tax dispute". WISH-TV. Retrieved 14 July 2018.