Takkanot Shum

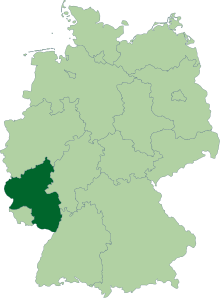

The Takkanot Shum (Hebrew: תקנות שו"ם), or Enactments of SHU"M were a set of decrees formulated and agreed upon over a period of decades by the leaders of three of the central cities of Medieval Rhineland Jewry: Speyer, Worms, and Mainz. The initials of the Hebrew names for these cities, Shpira, Vermayza, and Magentza form the initials SHUM. While these regulations were intended to address the problems of that time, they had an effect on European Jewry that lasted centuries.[1]

Background

Following the devastation of the Jewish communities of the Rhineland during the People's Crusade, Jews who had formerly made their livings as itinerant merchants could no longer travel safely, and had to find careers in the cities which they lived. Many became local merchants; others became moneylenders. This drastically increased the rate of commerce between Jews and non-Jews, and, thus, litigation both internally amongst Jews and between Jews and non-Jews. Simultaneously, heavy taxes were being levied on the Jewish communities by the local government, taxes which many Jews at the time felt were being unfairly distributed by the leaders of the local kehilla. The increasing internal and external pressures on the Jewish community, together with their recent near destruction during the Crusades, caused the leaders of the time to take the step of instituting broad decrees to strengthen their communities.[2][3]

Synod of the Takkanot

In or around 1160, a synod was held in Troyes. This synod was led by Rabbeinu Tam, his brother, the Rashbam, both grandchildren of Rashi, and Eliezer ben Nathan (the Ra'avan). Over 250 rabbis from communities all over France attended as well. A number of communal decrees were enacted at the synod covering both Jewish-Gentile relations as well as matters relating internally to the Jewish community.[4] Examples of such decrees include:

- The restriction requiring Jews engaged in monetary disputes amongst themselves to have the case decided by a Jewish beth din, and not a secular court, unless one of the parties was refusing to accept the ruling rendered by the beth din.

- A person disputing the kehillah’s tax assessment on him should pay the tax first and then bring the assessors to beth din.

- A person lending space to a community to act as a synagogue cannot restrict specific individuals from praying there. He can only rescind the permission in toto.[5]

Among the many new decrees implemented or older decrees strengthened was the famous ban of Rabbenu Gershom against polygamy.[6]

Synods of SHUM

The synod in Troyes was binding only on French Jewry. In or around 1196, the rabbis and community leaders throughout the entire Rhineland called a synod of their own in Mainz, in which they affirmed most of the decrees of the Troyes synod, and added a number of their own. The decrees did not take as firm hold as was desired, so twenty-four years later, in 1220, a second synod was convened in Mainz, in which the leaders of the generation re-affirmed the decrees enacted in the first synod.[4][6] Important historical figures attending one or both of these synods included David of Münzenberg, Simha of Speyer, Jacob ben Asher of Speyer, Eliezer ben Joel HaLevi, and Elazar Rokeach.[7]

These enactments covered both internal issues within the Jewish community as well as issues that involved interactions with the non-Jewish government of the time. Specific examples of enactments instituted or strengthened at the Rhineland synods include:

- The placement of a cherem on anyone who informed on another Jew until such time as restitution was made.

- The removal of all exceptions to community-imposed taxes.

- The prohibition against lending money to other Jews without ensuring strict adherence to the halakhot that dealt with loans.

- The prohibition against calling someone a mamzer or otherwise cast aspersions about the legal validity of his or her parents' marriage.

- The permission for the estate of a deceased person to be used to educate his or her children, even if the deceased indicated some other specific use for the funds.

There were many other decrees that dealt with various aspects of Jewish legal, financial, and religious life of the times.[8]

In 1223 a third synod was held in the Rhineland community, this time in Speyer. The main focus of this synod was the "Chalitzah takkana," but other decrees were discussed, including the prohibition against a one person either placing or lifting a cherem. To be either placed or lifted, such bans needed more than one community leader to agree. Notable attendees of this third synod included Elazar Rokeach and David ben Shaltiel.[9]

Modern adherence

While parts of various decrees still remain in force, the majority of the Takkanot Shum are no longer considered in force by most Ashkenazic Jewry. The decrees were instituted to deal with specific religious and sociological problems of the time, and were not considered to be placed in force for perpetuity, but for only as long as such issues existed.[10] However, there are two specific decrees still considered active today: the Dowry takkana and the Chalitzah takkana.[7]

Dowry takkana

At this time it was common to marry off daughters quite young, as soon as a suitable husband could be found and a dowry put together.[11] Combined with childhood diseases and a high general mortality rate this meant that it was not uncommon for young people to die within a short time of marriage, before their spouses had formed lasting relationships with their families. Under Jewish inheritance law, a husband is his wife's sole heir, but a wife does not inherit from her husband. Thus, no matter who died, the dowry, which represented a substantial sacrifice by the wife's parents for their daughter's happiness, would end up with the husband or his family. As a result, parents became reluctant to give their daughters large dowries, which in turn led to difficulty in finding them husbands.[9] Therefore the synod of Troyes, led by Rabbenu Tam, decreed that if a husband or wife dies within a year of marriage without leaving a surviving child, the dowry would revert to the parents who had given it; if the death was within two years half the dowry would revert.[12] While Rabbenu Tam rescinded this decree before his death, it was reaffirmed by his students in the first synod of SHUM.[9] This decree is today incorporated by reference into the standard Ashkenazi prenuptial contract (tena'im), with the phrase "and in case of absence [a euphemism for death] it will stand as the decree of ShUM"; in some communities even this elliptical mention of death is thought unlucky at a wedding, so it is merely hinted at with the cryptic phrase "and in case, etc."[13] Even if it is not explicitly referenced at all, or if there is no contract, it is assumed that the parties consented to it unless it is explicitly excluded.[14]

Chalitzah takkana

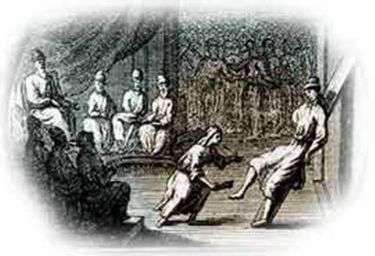

When a husband died childless, there is a mitzvah for a surviving brother to perform either yibbum or halizah. Already in the times of the Talmud, performing yibbum was deprecated in favor of halitza for various reasons.[15][16] The decrees enacted in the various synods of SHUM dealt with the time span allowed and the disbursement of the deceased's property after halitzah.[9]

The original decree, discussed at all three synods of SHUM, instituted a time limit of three months after the husband's death within which to perform yibbum or halitzah (although yibbum was rarely, if ever, performed) and after the halitzah, a beth din would decide upon the disbursement of the estate, with no recourse for the brother performing halitzah to subsequently sue. This decree was yet again re-affirmed 60 years later by Meir of Rothenburg.[9]

However, in 1381, another synod was held in Mainz that changed the disbursement—instituting an even split between the widow and all surviving brothers. This was a change from previous tradition in which, most often, the brother performing the halitzah would receive the ketubah monies, as well as usually receiving most, if not all, of the surviving estate. This version is the second of the decrees still enforced today.[10]

See also

- German Jews

- Jewish community of Speyer

- Posek

References

- Hirschman, Raphael (May 27, 2009). Ben Nun, Dov (ed.). "The Takkanos of SHUM". Mishpacha (260 (Kolmos Supplement)): 16–23. OCLC 57819059. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- Hirschman, 16–17

- Weiss, Moshe (2004). "Rashi and the Crusades". A brief history of the Jewish people (Google Book Search). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 101–102. ISBN 0-7425-4402-8. LCCN 00067546. OCLC 45463461. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- "Synods". Jewish Virtual Library. 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- Hirschman, 18

- Hirschman, 19

- Hirschman, 21

- Hirschman, 20–21

- Hirschman, 22

- Hirschman, 23

- Tosafot Kiddushin (41a) sv assur le'adam

- Rama, Even Ha'ezer 53:3

- Mordechai Farkash, Seder Kiddushin Venisu'in 1:11

- Beth Shmuel 53:20

- Talmud Bekhorot 13a

- Talmud Yevamot 39b