TREM2

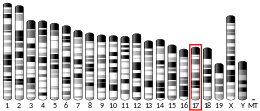

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 also known as TREM-2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TREM2 gene.[5][6][7]

Function

Monocyte/macrophage- and neutrophil-mediated inflammatory responses can be stimulated through a variety of receptors, including G protein-linked 7-transmembrane receptors (e.g., FPR1), Fc receptors, CD14 and Toll-like receptors (e.g., TLR4), and cytokine receptors (e.g., IFNGR1). Engagement of these receptors can also prime myeloid cells to respond to other stimuli. Myeloid cells express receptors belonging to the Immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily, such as TREM2, or to the C-type lectin superfamily. Depending on their transmembrane and cytoplasmic sequence structure, these receptors have either activating (e.g., KIR2DS1) or inhibitory functions (e.g., KIR2DL1).[7]

Upon stimulation, TREM2 engages DAP12, causing the two tyrosines on its immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) to become phosphorylated. Spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) then docks to these phosphorylation sites and activates the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) cascade which promotes several cellular functions such as cell survival, phagocytosis, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and cytoskeletal rearrangement via various transcription factors including AP1, NF-κB, and NFAT.[8]

Clinical significance

Homozygous mutations in TREM2 are known to cause rare, autosomal recessive forms of dementia with an early onset and presenting with[6] or without[9] bone cysts and fractures.

A rare missense mutation (rs75932628-T) in the gene encoding TREM2, (predicted to result in an R47H substitution), confers a significant risk of Alzheimer's disease. Given the reported antiinflammatory role of TREM2 in the brain, it is suspected of interfering with the brain’s ability to prevent the buildup of plaque.[10][11] TREM2 mutations increase the risk of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease. TREM2 interacts with DAP12 in microglia to trigger phagocytosis of amyloid beta peptide and apoptotic neurons without inflammation. Mutations in TREM2 impair the normal proteolytic maturation of the protein which in turn interferes with phagocytosis and may therefore contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease.[12]

Soluble TREM2 has been detected in human cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), where it was found to be elevated in CSF of patients with multiple sclerosis and other inflammatory neurological conditions in comparison to patients without inflammatory neurologic disorders.[13]

A recent study from Cruchaga lab[14] identified MS4A4A as a major regulator of soluble TREM2 levels.[15] Cruchaga and his team also demonstrated that TREM2 is implicated on disease in general and not only in those individuals that carry TREM2 risk variants. Using Mendelian randomization, they also demonstrate that highly soluble TREM2 levels are protective. These results provide a mechanistic explanation of one the AD risk GWAS loci, MS4A4A: this gene modified risk for AD by modulating TREM2 levels.

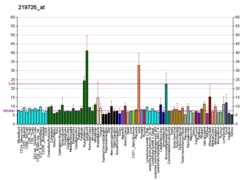

TREM2 transcript levels are upregulated in the lung parenchyma of smokers.[16]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000095970 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000023992 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Bouchon A, Dietrich J, Colonna M (May 2000). "Cutting edge: inflammatory responses can be triggered by TREM-1, a novel receptor expressed on neutrophils and monocytes". Journal of Immunology. 164 (10): 4991–5. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.4991. PMID 10799849.

- Paloneva J, Manninen T, Christman G, Hovanes K, Mandelin J, Adolfsson R, Bianchin M, Bird T, Miranda R, Salmaggi A, Tranebjaerg L, Konttinen Y, Peltonen L (September 2002). "Mutations in two genes encoding different subunits of a receptor signaling complex result in an identical disease phenotype". American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 656–62. doi:10.1086/342259. PMC 379202. PMID 12080485.

- "Entrez Gene: TREM2 triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2".

- Xing J, Titus AR, Humphrey MB (2015). "The TREM2-DAP12 signaling pathway in Nasu-Hakola disease: a molecular genetics perspective". Research and Reports in Biochemistry. 5: 89–100. doi:10.2147/RRBC.S58057. PMC 4605443. PMID 26478868.

- Guerreiro RJ, Lohmann E, Brás JM, Gibbs JR, Rohrer JD, Gurunlian N, Dursun B, Bilgic B, Hanagasi H, Gurvit H, Emre M, Singleton A, Hardy J (January 2013). "Using exome sequencing to reveal mutations in TREM2 presenting as a frontotemporal dementia-like syndrome without bone involvement". JAMA Neurology. 70 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.579. PMC 4001789. PMID 23318515.

- Hickman SE, El Khoury J (April 2014). "TREM2 and the neuroimmunology of Alzheimer's disease". Biochemical Pharmacology. 88 (4): 495–8. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.021. PMC 3972304. PMID 24355566.

- Kolata G (14 November 2012). "Alzheimer's Tied to Mutation Harming Immune Response". New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- Lue LF, Schmitz C, Walker DG (August 2015). "What happens to microglial TREM2 in Alzheimer's disease: Immunoregulatory turned into immunopathogenic?". Neuroscience. 302: 138–50. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.050. PMID 25281879.

- Piccio L, Buonsanti C, Cella M, Tassi I, Schmidt RE, Fenoglio C, Rinker J, Naismith RT, Panina-Bordignon P, Passini N, Galimberti D, Scarpini E, Colonna M, Cross AH (November 2008). "Identification of soluble TREM-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and its association with multiple sclerosis and CNS inflammation". Brain. 131 (Pt 11): 3081–91. doi:10.1093/brain/awn217. PMC 2577803. PMID 18790823.

- "NeuroGenomics and Informatics".

- Deming, Y; Filipello, F; Cignarella, F; Cantoni, C; Hsu, S; Mikesell, R; Li, Z; Del-Aguila, JL; Dube, U; Farias, FG; Bradley, J; Budde, J; Ibanez, L; Fernandez, MV; Blennow, K; Zetterberg, H; Heslegrave, A; Johansson, PM; Svensson, J; Nellgård, B; Lleo, A; Alcolea, D; Clarimon, J; Rami, L; Molinuevo, JL; Suárez-Calvet, M; Morenas-Rodríguez, E; Kleinberger, G; Ewers, M; Harari, O; Haass, C; Brett, TJ; Benitez, BA; Karch, CM; Piccio, L; Cruchaga, C (14 August 2019). "The MS4A gene cluster is a key modulator of soluble TREM2 and Alzheimer's disease risk". Science Translational Medicine. 11 (505): eaau2291. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aau2291. PMC 6697053. PMID 31413141.

- Pintarelli G, Noci S, Maspero D, Pettinicchio A, Dugo M, De Cecco L, Incarbone M, Tosi D, Santambrogio L, Dragani TA, Colombo F (September 2019). "Cigarette smoke alters the transcriptome of non-involved lung tissue in lung adenocarcinoma patients". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 13039. Bibcode:2019NatSR...913039P. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49648-2. PMC 6736939. PMID 31506599.

Further reading

- Piccio L, Buonsanti C, Cella M, Tassi I, Schmidt RE, Fenoglio C, Rinker J, Naismith RT, Panina-Bordignon P, Passini N, Galimberti D, Scarpini E, Colonna M, Cross AH (November 2008). "Identification of soluble TREM-2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and its association with multiple sclerosis and CNS inflammation". Brain. 131 (Pt 11): 3081–91. doi:10.1093/brain/awn217. PMC 2577803. PMID 18790823.

- Allcock RJ, Barrow AD, Forbes S, Beck S, Trowsdale J (February 2003). "The human TREM gene cluster at 6p21.1 encodes both activating and inhibitory single IgV domain receptors and includes NKp44". European Journal of Immunology. 33 (2): 567–77. doi:10.1002/immu.200310033. PMID 12645956.

- Soragna D, Papi L, Ratti MT, Sestini R, Tupler R, Montalbetti L (June 2003). "An Italian family affected by Nasu-Hakola disease with a novel genetic mutation in the TREM2 gene". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 74 (6): 825–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.6.825-a. PMC 1738498. PMID 12754369.

- Cella M, Buonsanti C, Strader C, Kondo T, Salmaggi A, Colonna M (August 2003). "Impaired differentiation of osteoclasts in TREM-2-deficient individuals". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 198 (4): 645–51. doi:10.1084/jem.20022220. PMC 2194167. PMID 12913093.

- Paloneva J, Mandelin J, Kiialainen A, Bohling T, Prudlo J, Hakola P, Haltia M, Konttinen YT, Peltonen L (August 2003). "DAP12/TREM2 deficiency results in impaired osteoclast differentiation and osteoporotic features". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 198 (4): 669–75. doi:10.1084/jem.20030027. PMC 2194176. PMID 12925681.

- Montalbetti L, Ratti MT, Greco B, Aprile C, Moglia A, Soragna D (2005). "Neuropsychological tests and functional nuclear neuroimaging provide evidence of subclinical impairment in Nasu-Hakola disease heterozygotes". Functional Neurology. 20 (2): 71–5. PMID 15966270.

- Bianchin MM, Lima JE, Natel J, Sakamoto AC (February 2006). "The genetic causes of basal ganglia calcification, dementia, and bone cysts: DAP12 and TREM2". Neurology. 66 (4): 615–6, author reply 615–6. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000216105.11788.0f. PMID 16505336.