Tâb

Tâb is the Egyptian name of a running-fight board game played in several Muslim (mostly Arab) countries, and a family of similar board games played in North Africa (as sîg) and Western Asia, from Iran to West Africa and from Turkey to Somalia, where a variant called deleb is played. The rules and boards can vary widely across the region though almost all consist of boards with three or four rows. A reference to "at-tâb wa-d-dukk" (likely a similar game) occurs in a poem of 1310 CE.[1]

| |

| Years active | First documented in 1600s. |

|---|---|

| Genre(s) | Board game Running-fight game Dice game |

| Players | 2 |

| Setup time | 30 seconds - 1 minute |

| Playing time | 5–60 minutes |

| Random chance | Medium (dice rolling) |

| Skill(s) required | Strategy, tactics, counting, probability |

| Synonym(s) | Sîg, Deleb |

Gameplay

The game described here was recorded by Edward William Lane in Egypt in the 1820s.

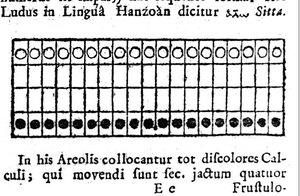

Egyptian tâb is played by two players on a board, often delineated at the ground. The board is four squares wide, and usually an odd number of squares long, usually from 7 to 15, but formerly up to 29 squares. Numbering the four rows 1, 2, 3 and 4, from the start one player has one (nominally) white piece in each field of row 1, and the other a (nominally) black piece in each field of row 4. The pieces may be stones or made from burnt clay. In Egypt, the pieces are referred to as kelb, meaning dog.

As in the Ancient Egyptian game Senet and the Korean game Yut, four sticks of a roughly semi-circular cross-section are used as dice. The flat sides are (nominally) white, and the rounded sides are (nominally) black. The value of a throw depends on the number of black and white sides showing, as indicated in the following table.[2]

| White up | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Move | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Extra throw | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Name | Sitteh | Tâb | Itneyn | Teláteh | Arba'ah |

| Approx. prop.[3] | 6% | 25% | 38% | 25% | 6% |

For each piece, the first move must be a tâb, which converts the piece from a Christian to a Muslim in addition to moving it one field ahead. Typically all initial tâbs are used to convert pieces, and only later are tâbs used for other purposes.[4]

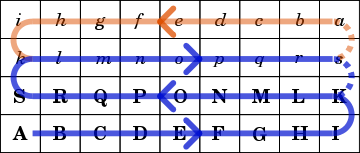

The pieces move as shown in the diagram, here shown for "White" starting in its home row A-I. The other player ("Black" starting in home row a-i) moves in the same way, meaning that black and white pieces move in the same direction through each of the rows. When a white piece gets to square s, White can choose to send the piece to a or back to K. However, a given piece can only go into its opponent's home row (for White, a-i) once; the next time it must go back to K, thereafter merely circulating through the 2 middle rows. Once in its opponent's home row, a piece cannot move any further as long as there are any pieces left in its own home row. No piece ever returns to its own home row.

A piece moving to a square occupied by one or more enemy pieces will knock those pieces off the board. A piece moving to a square occupied by one or more friendly pieces is placed on top of those, and they move as one piece thereafter. If such a stack moves to a row where one of the pieces has been before, the stack is reduced to just one piece, the other pieces being removed from the board. However, the player is not required to utilize a throw leading to such move. A tâb throw can be used to break up a stack so that the pieces move individually again.

The game continues till one player has lost all pieces, whereby the other player wins.

A game position is not given by the position of all pieces only, but also by their pre-history, substantially complicating the game.

See also

Notes

- Depaulis "Jeux" 2001, p 53-66.

- Lane 1860, p 347.

- The approximate probabilities shown are based on the assumption that the black and white sides have equal probabilities, which typically is correct to within a few percent.

- Lane 1860, p 348.

References

- P. Waage Jensen, Brik- og brætspil. ISBN 87-567-2755-0 (in Danish)

- Lane, Edward William (1860), The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (Fifth ed.), London: John Murray

- Depaulis, Thierry (2001), "Jeux de parcours du monde arabo-musulman (Afrique du Nord et Proche-Orient)" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 53–76 (English summary p 149), ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962

- Depaulis, Thierry (2001), "An Arab game in the North Pole?" (PDF), Board Games Studies, Leiden: CNWS Publications, 4: 77–82, ISBN 90-5789-075-5, ISSN 1566-1962