Szabla

Szabla (Polish pronunciation: [ˈʂabla]; plural: szable) is the Polish word for sabre.

The sabre was in widespread use in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Early Modern period, especially by light cavalry during 17th century. The sabre became widespread in Europe following the Thirty Years' War and was also adopted by infantry. In particular, it served as one of the symbols of the nobility and aristocracy (szlachta), who considered it to be one of the most important pieces of men's traditional attire.

Types

Hungarian-Polish szabla

The first type of szabla, the Hungarian-Polish (węgiersko-polska), was popularized among the szlachta during the reign of the Transylvanian-Hungarian King of Poland Stefan Batory in the late 16th century. It featured a large, open hilt with a cross-shaped guard formed from quillons and upper and lower langets and a heavy blade. The single edged blade was either straight or only slightly curved. Since the saber provided little to no hand protection, a chain was attached from the cross-guard to the pommel.[1] Since a number of such weapons were made by order of the king himself during his reform of the army and were engraved with his portrait, this kind of sabre is also referred to as batorówka – after Batory's name.

Armenian-style szabla

In the late 17th century the first notable modification of the sabre appeared. Unlike the early "Hungarian-Polish" type, it featured a protected hilt and resembled the curved sabres of the East. It was hence called the Armenian sabre, possibly after Armenian merchants and master swordsmiths who formed a large part of arms makers of the Commonwealth at those times. In fact the Armenian sabre developed into three almost completely distinct types of swords, each used for a different purpose. Their popularity and efficiency made the Polish nobles abandon the broadswords used in Western Europe.

- Czeczuga was a curved sabre with a small cross-guard with an ornamented open hilt and a hood offering partial protection to the hand.

- Ordynka was a heavier weapon used by the cavalry. It resembled a mixture of all the features of the Czeczuga with a heavier and more durable hilt and blade of the short sword.

- Armenian karabela was the first example of a ceremonial sword used by the szlachta. It had both its blade and cross-guard curved, and had a short grip. It was engraved and decorated with precious stones and ivory. Used throughout the ages, in the 18th century it evolved into a standard karabela, used both as a part of attire and in combat (see below).

Hussar szabla

The hussar sabre was perhaps the best-known type of szabla of its times and became a precursor to many other such European weapons. Introduced around 1630, it served as a Polish cavalry mêlée weapon, mostly used by heavy cavalry, or Polish Hussars. Much less curved than its Armenian predecessors, it was ideal for horseback fighting and allowed for much faster and stronger strikes.[1] The heavier, almost fully closed hilt offered both good protection of the hand and much better control over the sabre during a skirmish. Two feather-shaped pieces of metal on both sides of the blade called moustache (wąsy) offered greater durability of the weapon by strengthening its weakest point: the joint between the blade and the hilt. The soldier fighting with such sabre could use it with his thumb extended along the back-strap of the grip for even greater control when 'fencing' either on foot or with other experienced horsemen, or by using the thumb-ring, a small ring of steel or brass at the junction of the grip and the cross-guard through which the thumb is placed, could give forceful downward swinging cuts from the shoulder and elbow with a 'locked' wrist against infantry and less experienced horsemen. This thumb ring also facilitated faster 'recovery' of the weapon for the next cut. A typical hussar szabla was relatively long, with the average blade of 85 centimetres (33 in) in total. The tip of the blade, usually some 15 to 18 centimetres long, was in most cases double-edged. Such sabres were extremely durable yet stable, and were used in combat well into the 19th century.

The Polish and Hungarian szabla's design influenced a number of other designs in other parts of Europe and led to the introduction of the sabre in Western Europe. An example that bears a considerable resemblance is the famous British 1796 pattern Light Cavalry Sabre which was designed by Captain John Gaspard le Marchant after his visits "East" to Central and Eastern Europe and research into these and other nations' cavalry tactics and weapons. Poland had ceased to exist as a separate nation by this time but their other co-nation from previous centuries, Hungary, was still an existing nation, and as this was the source of all things "Hussar", it was the Polish-Hungarian szable of 150 years earlier rather than the oft quoted Indian tulwar that were the main source of inspiration for the first "mainly cutting" sabre in the British Army. This same "1796" sabre was taken up by the King's Hanoverian troops and also by the Prussians under General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher who attempted to give his name to the weapon, almost universally known as "the 1796 Light Cavalry Sabre" in the rest of Europe. This weapon also found its way into the cavalry of the newly formed United States in the War of 1812.

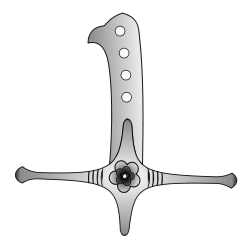

Karabela

The karabela entered service around 1670.

A karabela was a type of szabla popular in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 1670s.

The word "karabela" does not have well-established etymology, and different versions are suggested.[2] For example, Zygmunt Gloger suggests derivation from the name of the Iraqi city of Karbala, known for trade of this kind of sabres.[3]

Other types

- Kosciuszkowska, a variant popularized during the Kościuszko Uprising;

- Szabla wz.34 ("model 34 szabla"), a 20th-century variant produced from 1934 in the Second Polish Republic for Polish cavalry; just about 40,000 were made.

Technique

Stance

There are many stances for the Szabla, such as Back-Weighted, Toes Forward, Even-Weighted, and Forward-Weighted.

Back-Weighted is a stance in which the back leg is bent, and put the weight onto. While the front leg is free to move with little weight in the case of an attack by the opponent.[1]

Toes Forward is a stance in which weight is evenly distributed between each leg. The balls of the feet are planted on the ground while the toes are raised.[1]

Even-Weighted is a stance in between Forward-weighted and Back-weighted.[1]

Forward-Weighted is a stance in which most of the weight is on the front leg, allowing the back leg to move freely. This allows the person to lean into or away from the attacker.[1]

Footwear

Proper footwear was also very important when it comes to stance. There are two main types of footwear used in Poland at the time, Polish Hussar Boots and Turkish footwear.[1]

Polish Hussar Boots were used in the 17th century. They came in mostly yellow, gold, or maize coloring. They had a high heel and also allows for the ball of the foot to rest naturally on the ground.[1] Despite the name, Turkish footwear was common in 17th century Poland. Like the Polish Hussar Boots, these boots had a high heel for attaching spurs, as well as allowing the ball of the foot to rest on the ground.[1]

See also

References

- Marsden (2015)

- "Bulletin de la Société polonaise de linguistique", vol. 58, p. ,

- Zygmunt Gloger, "Księga rzeczy polskich" 1896, p. 148

- W. Kwaśniewicz, Leksykon broni białej i miotającej, Warszawa, Dom wydawniczy Bellona, 2003 ISBN 83-11-09617-1.

- W. Kwaśniewicz, Dzieje szabli w Polsce, Warszawa, Dom wydawniczy Bellona, 1999 ISBN 83-11-08894-2.

- Andrzej Nadolski "Polska broń. Biała broń", Warszawa 1974.

- Wojciech Zablocki, "Ciecia Prawdziwa Szabla", Wydawnictwo "Sport i Turystyka" (1989) (English abstract by Richard Orli, 2000, kismeta.com).

- Richard Marsden, The Polish Saber, Tyrant Industries (2015)