Synthetic resin

Synthetic resins are industrially produced resins, typically viscous substances that convert into rigid polymers by the process of curing. In order to undergo curing, resins typically contain reactive end groups,[2] such as acrylates or epoxides. Some synthetic resins have properties similar to natural plant resins, but many do not.[3]

Synthetic resins are of several classes. Some are manufactured by esterification of organic compounds. Some are thermosetting plastics in which the term "resin" is loosely applied to the reactant or product, or both. "Resin" may be applied to one of two monomers in a copolymer, the other being called a "hardener", as in epoxy resins. For thermosetting plastics that require only one monomer, the monomer compound is the "resin". For example, liquid methyl methacrylate is often called the "resin" or "casting resin" while in the liquid state, before it polymerizes and "sets". After setting, the resulting PMMA is often renamed acrylic glass, or "acrylic". (This is the same material called Plexiglas and Lucite).

Types of synthetic resins

The classic variety is epoxy resin, manufactured through polymerization-polyaddition or polycondensation reactions, used as a thermoset polymer for adhesives and composites.[4] Epoxy resin is two times stronger than concrete, seamless and waterproof. Accordingly, it has been mainly in use for industrial flooring purposes since the 1960s. Since 2000, however, epoxy and polyurethane resins are used in interiors as well, mainly in Western Europe.

Synthetic casting "resin" for embedding display objects in Plexiglas/Lucite (PMMA) is simply methyl methacrylate liquid, into which a polymerization catalyst is added and mixed, causing it to "set" (polymerize). The polymerization creates a block of PMMA plastic ("acrylic glass") which holds the display object in a transparent block.

Another synthetic polymer, sometimes called by the same general category, is acetal resin. By contrast with the other synthetics, however, it has a simple chain structure with the repeat unit of form −[CH2O]−.

Ion exchange resins are used in water purification and catalysis of organic reactions. See also AT-10 resin, melamine resin. Certain ion exchange resins are also used pharmaceutically as bile acid sequestrants, mainly as hypolipidemic agents, although they may be used for purposes other than lowering cholesterol.

Solvent Impregnated Resins (SIRs) are porous resin particles which contain an additional liquid extractant inside the porous matrix. The contained extractant is supposed to enhance the capacity of the resin particles.

A large category of resins, which constitutes 75% of resins used, is that of the unsaturated polyester resins.

The production of PVC entails the production of "vinyl chloride resins", which differ in the degree of polymerization.[5]

Health hazards

Health hazards potentially associated with synthetic resins are typically less of a concern than the hazards associated with the cured products, which are more commonly in contact with consumers. Issues of interest include the effects of unconsumed monomers and oligomers and solvent carriers.

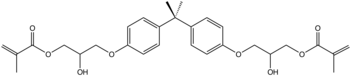

Dental restorative materials based on bis-GMA-containing resins[6] can break down into or be contaminated with the related compound bisphenol A, a potential endocrine disrupter. However, no negative health effects of bis-GMA use in dental resins have been found.[7][8]

See also

References

- Pham, Ha Q.; Marks, Maurice J. (2012). "Epoxy Resins". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_547.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- Chemistry, International Union of Pure and Applied. IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology. iupac.org. IUPAC. doi:10.1351/goldbook.RT07166.

- Collin, Gerd; et al. (2005). "Resins, Synthetic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_089. ISBN 3527306730.

- Cripps, David. "Epoxy Resins". NetComposites. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- M. W. Allsopp, G. Vianello (2012). "Poly(Vinyl Chloride". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_717.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Robert G. Craig, Dieter Welker, Josef Rothaut, Klaus Georg Krumbholz, Klaus‐Peter Stefan, Klaus Dermann, Hans‐Joachim Rehberg, Gertraute Franz, Klaus Martin Lehmann, Matthias Borchert (2006). "Dental Materials". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_251.pub2.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Soderholm KJ, Mariotti A (February 1999). "Bis-GMA–based resins in dentistry: are they safe?". The Journal of the American Dental Association. 130 (2): 201–209. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0169. PMID 10036843.

- Ahovuo-Saloranta, Anneli; Forss, Helena; Walsh, Tanya; Nordblad, Anne; Mäkelä, Marjukka; Worthington, Helen V. (31 July 2017). "Pit and fissure sealants for preventing dental decay in permanent teeth". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD001830. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001830.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6483295. PMID 28759120.