Syndrome of subjective doubles

The syndrome of subjective doubles is a rare delusional misidentification syndrome in which a person experiences the delusion that they have a double or Doppelgänger with the same appearance, but usually with different character traits, that is leading a life of its own.[1][2] The syndrome is also called the syndrome of doubles of the self,[3] delusion of subjective doubles,[1] or simply subjective doubles.[4] Sometimes, the patient is under the impression that there is more than one double.[1] A double may be projected onto any person, from a stranger to a family member.[4]

This syndrome is often diagnosed during or after the onset of another mental disorder, such as schizophrenia or other disorders involving psychotic hallucinations.[5] There is no widely accepted method of treatment, as most patients require individualized therapy. The prevalence of this disease is relatively low, as few cases have been reported since the disease was defined in 1978 by George Nikolaos Christodoulou (b.1935), a Greek-American Psychiatrist.[5][6] However, subjective doubles is not clearly defined in literature,[7] and, therefore may be under-reported.[5]

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of the syndrome of subjective doubles are not clearly defined in medical literature; however, there are some defining features of the delusion:[5]

- The existence of the delusion, by definition, is not a widely accepted cultural belief.

- The patient insists that the double he/she sees is real even when presented with contradictory evidence.

- Paranoia and/or spatial visualization ability impairments are present.

Similarities to other disorders are often noted in literature. Prosopagnosia, or the inability to recognize faces, may be related to this disorder due to the similarity of symptoms.[7] Subjective doubles syndrome is also similar to delusional autoscopy, also known as an out-of-body experience, and therefore is occasionally referred to as an autoscopic type delusion.[1][8] However, subjective doubles delusion differs from an autoscopic delusion: autoscopy often occurs during times of extreme stress, and can usually be treated by relieving the said stressor.[5]

The syndrome of subjective doubles is usually accompanied by another mental disorder or organic brain syndrome, and may appear during or after the onset of the other disorder.[2] Often, co-occurrence of subjective doubles with other types of delusional misidentification syndromes, especially Capgras syndrome,[9] also occurs.[10]

Several variations of the syndrome have been reported in literature:

- The doubles may appear at different ages of oneself.[1]

- Some patients describe their double as both a physically and psychologically identical copy, rather than a purely physical copy. This is also known as clonal pluralization of the self, another type of delusional misidentification syndrome that may or may not be the same type of disorder (see #Controversy, below). In this case, depersonalization may be a symptom.[9]

- Reverse subjective doubles occurs when the patient believes his/her own self (either physical or mental) is being transformed into another person.[1][7][11] (see the case of Mr. A in #Presentation)

Presentation

The following case describes a patient who was diagnosed with psychotic depression, bipolar disorder, and the syndrome of subjective doubles:

Taken from Kamanitz et al., 1989:[5]

"Mrs. B. is a 50-year-old white married homemaker and the mother of five children with three previous psychiatric hospitalizations for depression and bipolar illness. [...] She firmly believed that another Mrs. B. existed who had replaced herself in her husband's affections. [...] Mrs. B. was convinced that the 'grooves in her fingers were smoother,' and that the double had taken her fingerprints. She was so concerned about the existence of another Mrs. B. that she required the constant presence of her driver's license to reassure herself that she was the real Mrs. B. In addition to her delusional belief, Mrs. B. reported that she had actually seen the other Mrs. B. She believed that the other Mrs. B. was also a patient in the unit who looked exactly like her facially but was heavier in the body. (Another, younger, patient, who was pregnant, was actually the person upon whom this illusion was superimposed.)"

The following case describes a patient who has been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder along with multiple delusional misidentification syndromes (subjective doubles, Capgras delusion, intermetamorphosis):

Taken from Silva et al., 1994:[10]

"Mr. B believed that five physical copies of himself existed. Each copy had a different mind than his own. On one occasion, he thought himself to have been Jesus Christ, but denied having undergone any bodily changes. Mr. B stated that five replicas of the city in which he lived existed as well as the existence of five different planet earths. He, however, acknowledged having lived on only one of these earths. Mr. B had a history of several arrests for attacking police officers, whom he believed were impostor replicas of real police officers."

The following case describes a patient who has been diagnosed with chronic paranoid schizophrenia and reverse subjective doubles:

Taken from Vasavada and Masand, 1992:[11]

"Mr. A, a 40-year-old divorced white male, was hospitalized for his complaint that his identity had been changed in the last six years. He stated that he was not Mr. A but Mr. B and preferred to be called by that name. [...] When asked to describe Mr. B, he replied that the only thing he remembered was that Mr. B was an orphan and had made his fortune by working hard. He denied that Mr. B had any family members. He would get angry when addressed as Mr. A and would insist on being called Mr. B. [...] In the above case our patient believed that he had been changed both physically (face, fingerprints, etc.) and psychologically (he could recount details of his life as Mr. A but few as Mr. B)."

Causes

Subjective doubles is commonly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.[5][9] The cause of the disorder is difficult to ascertain not only because of its rarity, but also due to the simultaneous presence of other disorders. While the physiological cause of the syndrome of subjective doubles has not been found, many hypotheses exist.[2]

Some researchers believe that the syndrome of subjective doubles appears as a symptom of another disorder instead of a disorder of its own.[7] (see #Controversy, below)

The syndrome of subjective doubles may also be related to substance dependence.[1]

Another hypothesis states that subjective doubles is result of hyper-identification, linked to over-activity in certain areas of the brain, thereby causing the patient see familiar aspects of the self in strangers.[4][12]

Some hypothesize that this delusion is a result of facial processing deficiencies, as it has seemingly similar symptoms of prosopagnosia; however, it must be noted that recognition of most faces is impaired in this delusion.[7] Facial processing deficiencies also do not account for the occasion in which multiple doubles are reported.[2]

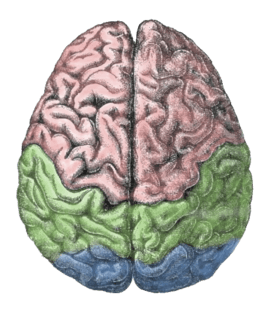

Another hypothesis is that a "disconnection" between the right and left hemispheres may cause the delusional symptoms.[2] This hypothesis relies heavily on the theory of lateralization of brain function, or left brain vs. right brain theory. In this hypothesis, the inability of the right hemisphere to "check" the left hemisphere causes the individual to succumb to delusions of self-awareness created by the left hemisphere.[4]

Brain damage

One hypothesis is that brain dysfunction (either due to physical damage or damage from an organic disorder) in the right hemisphere, temporal lobe, and/or bi-frontal lobes causes the delusion of subjective doubles.[9] Physical damage resulting in the subjective doubles delusion often includes, but is not limited to, brain lesions or traumatic brain injury.[2][4] Suspected organic causes of brain damage that may lead to subjective doubles include disorders such as epilepsy.[1]

Because other mental illnesses are commonly co-morbid with subjective doubles syndrome, it is unknown whether these types of brain injuries are linked to the delusion or the additional mental illness. For example, right hemisphere brain damage is associated with schizophrenia, which is commonly reported with the delusion of subjective doubles.[2]

Treatment

A widely accepted treatment for the syndrome of subjective doubles has not been developed. Treatment methods for this disease sometimes include the prescription of antipsychotic drugs, however, the type of drug prescribed depends on the presence of other mental disorders.[5] Antipsychotic drugs (also known as neuroleptics) such as risperidone, pimozide, or haloperidol may be prescribed to treat the underlying psychiatric illness.[5][13]

In addition to drug therapy, interpersonal counseling has also been suggested as a method to ease relations between the patient and his/her suspected doubles.[12] However, the relationship between the patient and his/her double is not always negative.[2]

Prognosis

Recovery from this syndrome is situational, as some drug therapies have been effective in some individuals but not others. Patients may live in a variety of settings, including psychiatric hospitals, depending on the success of treatment. With successful treatment, an individual may live at home. In many of the reported cases, remission of symptoms occurred during the follow-up period.[5]

This disorder can be dangerous to the patient and others, as a patient may interrogate or attack a person they believe to be a double.[7] Inappropriate behavior such as stalking and physical or psychological abuse has been documented in some case studies.[13] Consequently, many individuals suffering from this disorder are arrested for the resulting misconduct (see the case of Mr. B in #Presentation).[10][14]

History

This disorder was first defined in 1978 by Greek psychiatrist George N. Christodoulou, M.D., Ph.D, FRCPsych. Although the symptoms of subjective doubles have been described before 1978,[5] the disorder was not given a name until Christodoulou called it the syndrome of subjective doubles in the American Journal of Psychiatry. The article describes an 18-year-old female suffering from hebefreno-paranoid schizophrenia who believed that her next door neighbor had transformed her physical self into the patient's double.[3][6] The syndrome of subjective doubles and its variants were not given the name delusional misidentification syndromes until 1981.[2]

Doubles of the self have been reported in literature even before the syndrome was named by Christodoulou.[2] The first patient with symptoms of Capgras syndrome, another delusional misidentification syndrome, was reported in 1923 by Joseph Capgras and Jean Reboul-Lachaux. This patient, however, also experienced the delusion of subjective doubles,[15] but the appearance of doubles of the self were not addressed until Christodoulou's article in 1978.[6]

Controversy

Due to the rarity of this disorder and its similarities to other delusional misidentification syndromes, it is debated whether or not it should be classified as a unique disease. Because subjective doubles rarely appear as the only psychological symptom, it has been suggested that this syndrome is a rare presentation of symptoms of another psychological disorder. This syndrome is also not defined in the DSM-IV or ICD-10.[7][16]

Additionally, some researchers use varying definitions of the syndrome. While most declare that the double is a physical copy that is psychologically independent, some refer to a definition of a double as being both physically and psychologically identical. This is also known as clonal pluralization of the self, another less common delusion that is grouped with the other delusional misidentification syndromes.[9]

Popular culture

- In Michael R. Fletcher's dark fantasy novel Beyond Redemption (HARPER Voyager, 2015), a novel where belief and insanity shape reality, the Theocrat suffers from the Syndrome of Subjective Doubles.

- In Richard Ayoade's black comedy The Double the main character of Simon James is theorised to suffer from the Syndrome of Subjective Doubles with his doppelganger James Simon.

- William Peter Blatty’s novel Legion, a sequel to his novel The Exorcist, features a character named Dr. Vincent Amfortas who self-diagnoses his own case of Doppelganger Syndrome.

- Dan Simmons’ novel Drood features Victorian author Wilkie Collins as the narrator. In the book, Collins has had a lifelong case of Doppleganger Syndrome he refers to as “the Other Wilkie” and his imagined double is a key plot element.

References

- Vyas, Ahuja (2003). Textbook of Postgraduate Psychiatry. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishing. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-8171796489.

- Christodoulou, George N.; Margariti, M.; Kontaxakis, V. P.; Christodoulou, N. G. (2009). "The delusional misidentification syndromes: strange, fascinating, and instructive". Current Psychiatry Reports. 11 (3): 185–189. doi:10.1007/s11920-009-0029-6. PMID 19470279.

- Blom, Jan Dirk (2010). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer. p. 497. ISBN 978-1441912220.

- Devinsky, MD, Orrin (January 2009). "Delusional misidentifications and duplications: right brain lesions, left brain illusions". Neurology. 72 (1): 80–87. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000338625.47892.74. PMID 19122035.

- Kamanitz, Joyce R.; El-Mallakh, Rif S.; Tasman, Allan (1989). "Delusional Misidentification Involving the Self". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 177 (11): 695–698. doi:10.1097/00005053-198911000-00007. PMID 2681534.

- Christodoulou, G. N. (1978). "Syndrome of Subjective Doubles". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 135 (2): 249–51. doi:10.1176/ajp.135.2.249. PMID 623347.

- Cowen, Phillip (2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry, 6th ed. Oxford University Press. pp. 307–308. ISBN 978-0199605613.

- Mishara, Aaron L (2010). "Autoscopy: Disrupted self in neuropsychiatric disorders and anomalous conscious states." Handbook of phenomenology and cognitive science. Springer Netherlands. pp. 591–634. ISBN 978-9048126460.

- Schoenberg, Mike R. (2011). The Little Black Book of Neuropsychology: A Syndrome-Based Approach. Springer. p. 259. ISBN 978-0387707037.

- Silva, J. Arturo; Leong, G. B.; Garza-Trevifio, E. S.; Le Grand, J.; Oliva, D. Jr; Weinstock, R.; Bowden, C. L. (November 1994). "A Cognitive Model of Dangerous Delusional Misidentification Syndromes". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 39 (6): 1455–1467. PMID 7815025.

- Vasavada, Tarak; Masand, Prakash (1992). "An Unusual Variant of Capgras Syndrome". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 75 (3): 971–974. doi:10.2466/pms.1992.75.3.971. PMID 1454504.

- Christodoulou, George N. (1978). "Course and Prognosis of the Syndrome of Doubles". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 166 (1): 68–72. doi:10.1097/00005053-197801000-00010. PMID 619004.

- Silva, J. A.; Leong, G. B.; Weinstock, R.; Penny, G. (1995). "Dangerous Delusions of Misidentification of the Self". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 40 (4): 570–573. doi:10.1520/JFS13827J. PMID 7595292.

- Bourget, Domonique (June 2013). "Forensic considerations of substance-induced psychosis". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 41 (2): 168–173. PMID 23771929.

- Silva, J. Arturo; Gregory B. Leong (April 1991). "A Case of Subjective Fregoli Syndrome". Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 16 (2): 103–105. PMC 1188301. PMID 1911735.

- Atta, Kamil; Forlenza, Nicholas; Gujski, Mariusz; Hashmi, Seema; Isaac, George (2006). "Delusional Misidentification Syndromes: Separate Disorders or Unusual Presentation of Existing DSM-IV Categories?". Psychiatry. 3 (9): 56–61. PMC 2963468. PMID 20975828.