Sylvia Sleigh

Sylvia Sleigh (8 May 1916 – 24 October 2010) was a Welsh-born naturalised American realist painter.[1] She had traveled to New York City with her husband, Lawrence Alloway, to achieve her art career, which was a success. In the 1970s, she had gained a lot of popularity for her paintings and participated in the feminist art movement. She was well-known for reversing the genders of men and women. The goal was to show the stereotypes of men and women in artworks by painting men nude in women's poses. She had found inspiration from historical paintings created by male artists named Diego Velazquez, Titan, and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. She wanted the figures in her artworks to have similar poses to the historical paintings. The individuals in her art pieces weren't strangers. She had developed a close relationship with the individuals. Many of them are poets, art critics, feminist artists, and a spouse.[1]

Sylvia Sleigh | |

|---|---|

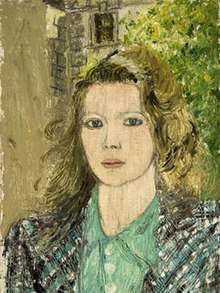

Self-Portrait at Belsize Square 1941 | |

| Born | 8 May 1916 |

| Died | 24 October 2010 (aged 94) New York, NY |

| Nationality | Welsh-American |

| Education | Brighton School of Art |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards |

|

| Website | sylviasleigh |

Sleigh had realized that men and women were unequal. So, she had developed the idea to create artwork that showed men and women being treated equally by reversing the genders stereotypes. She had attended art school and learned a few things that stood out. Men had covered their bodies with clothing, while women's bodies were always exposed. She had decided to paint attractive individuals with or without clothing. Some of the men's clothing was feminine. It had shown men gaining women's experience with being objectified and others. [1]

Early life and education

Sleigh was born in Llandudno, and raised in England. She had studied at the Brighton School of Art.[2] A person had told her that she wasn't a good artist. So, she had refused to paint for two years and waited for marriage to gain success. After attending college, she received a job at a clothing store for women on Bond Street to dress customers. She had the opportunity to make dresses and provide Vivien Leigh, an award-winning actress, with assistance. In Brighton, England, she had decided to continue her passion for fashion by opening her clothing store. She had to close her store because World War ll had prevented her from moving and completing work. [3] She had returned to painting and moved to London in 1941 after marrying her first husband, Michael Greenwood, a painter.[1] Her first solo exhibition was in 1953 at the Kensington Art Gallery.[4] It wasn't usual to display paintings of nude figures. At a young age, her mother, Katherine Miller, had gifted her with oil paintings and watercolors. She had admired the beauty of nature and painted wildflowers with friends. So, many of the art pieces displayed in her art exhibition were portraits, landscapes, and still life. She had painted portraits of students and other artists.[5][6] It wasn't a successful art exhibition because it was difficult for her artwork to gain attention as a female artist.[1] After divorcing Greenwood in 1954, Sleigh met her second husband, Lawrence Alloway, a curator and art critic, while taking evening classes to study art history at the University of London; they married in 1954 and moved to the United States in 1961.[2][7] The following year, Alloway became a curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.[7][8]

Work and feminism

Around 1970, from feminist principles, she painted a number of works reversing stereotypical artistic themes by featuring nude men in poses that were traditionally associated with women, like the reclining Venus or odalisque.[1] Some directly alluded to existing works, such as Philip Golub Reclining (1971), which appropriates the pose of the Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez.[9] She had used Nancy Spero and Golub's son as a model for the art piece.[1] This work also presents a reversal of the male-artist/female-muse pattern typical of the Western canon and is reflective of research into the position of women throughout the history of art as model, mistress, and muse, but rarely as artist−genius.[10] The Turkish Bath (1973), a similarly gender-reversed version of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres's painting of the same name, depicts a group of artists and art critics, including her husband, Lawrence Alloway (reclining at the lower right), Carter Radcliffe, John Perrault, and Scott Burton.[2][11] She had used similar poses from Ingres's painting, The Turkish Bath, by painting an individual playing the guitar with his back turned to the viewers. Her husband, Lawrence Alloway, looks at the viewers and leans to his side to do a pose. She wanted the nude men to be objectified and experience the male gaze, which was challenges that women had to face. Alloway and the other individuals look at the viewers to reject the male gaze. Ingre's painting had a maximum number of nude women. However, She had minimized the number of individuals in her art piece by painting six men. She had carefully painted individual hairs onto the males' bodies because society had ideologized men with tons of hair. A colorful rug with designs is in the background of the painting.[1] Throughout her career, Sleigh painted over thirty works that feature her husband as her subject. While somewhat idealized, Sleigh's figures remain highly individualized.[12] Since a child, she had only painted family and friends rather than strangers. It had continued into her adulthood. She felt more comfortable with painting her family and friends because they were her loved ones.[13]

In her male nudes, the subject "is used as a vehicle to express erotic feelings, just as male artists have always used the female nude"[14] In works such as Paul Rosano Reclining (1974) and Imperial Nude: Paul Rosano (1975), Sleigh portrayed her male subjects in stereotypical female poses in order to comment on past biases in which male artists have depicted sexualized female nudes.[15]

Other works equalize the roles of men and women, such as Concert Champêtre (1976), in which all of the figures are nude, unlike its similarly composed namesake by Titian (earlier credited to Giorgione), in which only the women are unclothed. As Sleigh explained, "I feel that my paintings stress the equality of men and women (women and men). To me, women were often portrayed as sex objects in humiliating poses. I wanted to give my perspective. I liked to portray both man and woman as intelligent and thoughtful people with dignity and humanism that emphasized love and joy."[16] Likewise, her painting of Lilith (1976), created as a component of The Sister Chapel, a collaborative installation that premiered in 1978, depicts the superimposed bodies of a man and woman to emphasize the fundamental similarities between the two genders.[17] She had created another well-known art piece called the A.I.R. Group Portrait (1977-1978), while the feminist art movement was growing. It is opposite to her paintings of nude male figures because she had painted women in the stereotypical role of men. She had painted a group of feminist artists in a room. Some of the feminist artists were Nancy Spero, Howardena Pindell, Agnes Denes, and Mary Beth Edelson. Half of the women were members of the Artist in Residence Gallery. The group of women wasn't naked, but they were fully clothed. Also, they weren't using women's stereotypical poses. Sleigh couldn't exclude herself from the painting. She had painted herself standing next to Howardena Pindell.[1]

Sleigh was a founding member of the all-women, artist-run SOHO 20 Gallery (est. 1973) and later joined A.I.R. Gallery (est. 1972).[18] She painted group portraits of both organizations.[19] Between 1976 and 2007, Sleigh painted a series of 36-inch portraits which feature women artists and writers, including Helène Aylon, Catharine R. Stimpson, Howardena Pindell, Selina Trieff, and Vernita Nemec.[20][21] Sleigh taught for some time at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and at the New School for Social Research.[2]

In a 2007 interview with Brian Sherwin, Sleigh was asked if gender equality issues in the mainstream art world, and the world in general, had changed for the better. She answered, "I do think things have improved for women in general there are many more women in government, in law and corporate jobs, but it's very difficult in the art world for women to find a gallery." According to Sleigh, there is still more that needs to be done in order for men and women to be treated as equals in the art world.[22]

In February 2008, Sleigh was interviewed by Lynn Hershman Leeson, who included a portion of the interview in her documentary !Women Art Revolution.[23]

Invitation to a Voyage

In 2006, Sylvia Sleigh gave away one of her most massive paintings called Invitation to a Voyage: The Hudson River at Fishkill to the Hudson River Museum. The art piece is the largest in her collection that took twenty years to complete (1979-1999). It is twenty feet wide. So, it had covered two walls in the art gallery. It is a painting in a total of fourteen wooden canvases with images that looked similar to Jean-Antoine Watteau, Giorgione, and Edouard Manet's historical paintings. A group of her friends, who are artists and art critics, relaxes next to the woods and banks of the Hudson River in New York City. They are picnicking, walking around, painting, and communicating with one another. It is an interactive art piece. Currently, in the art museum, half of the art piece hangs on the wall. The painting of the woods isn't displayed. It has an image of Sylvia Sleigh spending quality time with her husband, Lawrence Alloway. [24]

Recognition

During the last two decades of her life, Sleigh purchased or negotiated trades of over 100 works of art by other women and exhibited her growing collection at SOHO 20 Gallery in 1999.[21] These included paintings, sculptures, and prints by Cecile Abish, Dotty Attie, Helène Aylon, Blythe Bohnen, Louise Bourgeois, Ann Chernow, Rosalyn Drexler, Martha Edelheit, Audrey Flack, Shirley Gorelick, Nancy Grossman, Pegeen Guggenheim, Nancy Holt, Lila Katzen, Irene Krugman, Diana Kurz, Marion Lerner-Levine, Vernita Nemec, Betty Parsons, Ce Roser, Susan Sills, Michelle Stuart, Selina Trieff, Audrey Ushenko, Sharon Wybrants, and many others. In 2011, the Sylvia Sleigh Collection was donated to the Rowan University Art Gallery and forms the core of its permanent collection.[25]

Sylvia Sleigh had multiple solo exhibitions from the year 1953 to 2013, which was after her death. She had displayed most of her artworks in the South at Universities. Such as the University of Rhode Island, Ohio State University, Fordham University, and the University of Missouri-St. Louis. Most of her shows took place in New York City. In 2013, She had her last exhibition at Tate Liverpool in England. Multiple art Museums had displayed a collection of her artwork for the public to view, as well. The museums included The Hudson River Museum, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Akron Art Museum, National Portrait Gallery, and more. Many of her artworks got recognized, which had led to her receiving a couple of awards. [26]

As a visiting professor of painting, Sleigh was awarded the Edith Kreeger Wolf Distinguished Professorship at Northwestern University in 1977.[27] She received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1982 and a Pollock-Krasner Foundation Grant in 1985.[28]

In 2008, Sleigh was honored with the Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement by the College Art Association.[29] She was similarly recognized by the Women's Caucus for Art, which posthumously awarded Sleigh the organization's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011.[20] In Manhattan, New York, she had passed away from a stroke at the age of 94.[1]

References

- Grimes, William (25 October 2010). "Sylvia Sleigh, Provocative Portraitist and Feminist Artist, Dies at 94". New York Times. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- Brown, Betty Ann (1997). "Sleigh, Sylvia". In Gaze, Delia (ed.). Dictionary of Women Artists. 2. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. pp. 1280–1281.

- Grimes, William (2010-10-25). "Sylvia Sleigh, Provocative Portraitist and Feminist Artist, Dies at 94". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- Swartz, Anne (2011). "Sylvia Sleigh: Biography". Women's Caucus for Art: Honor Awards for Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts (PDF). Women's Caucus for Art. p. 26. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Otis Login Service - Stale Request". login.otis.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- "Sylvia Sleigh". www.artforum.com.

- Schlegel, Amy Ingrid, ed. (2001). "An Unnerving Romanticism:" The Art of Sylvia Sleigh and Lawrence Alloway. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Art Alliance.

- "Dictionary of Art Historians". Alloway, Lawrence. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Dunford, Penny (1990). A Biographical Dictionary of Women Artists in Europe and America Since 1850. Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Borzello, Frances (1998). Seeing Ourselves: Women's Self-Portraits. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Borzello, Frances (2 November 2001). "Nude awakening". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Schlegel, Amy Ingrid (16 June 2011). "A Tribute to Sylvia Sleigh (1916–2010)". College Art Association. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Otis Login Service - Stale Request". login.otis.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- Semmel, Joan; Kingsley, April (Spring–Summer 1980). "Sexual Imagery in Women's Art". Woman's Art Journal. 1 (1): 1–6. doi:10.2307/1358010. JSTOR 1358010.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Arnason, H.H.; Mansfield, Elizabeth (2013). History of Modern Art: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, Photography (7th ed.). Pearson Education Inc. p. 577.

- Love and joy Archived 2007-07-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Hottle, Andrew D. (2014). The Art of the Sister Chapel: Exemplary Women, Visionary Creators, and Feminist Collaboration. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 160.

- Broude, Norma; Garrard, Mary D., eds. (1994). The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- Moyer, Carrie (3 February 2010). "Sylvia Sleigh". The Brooklyn Rail. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Hottle, Andrew D. (2011). "Sylvia Sleigh". Women's Caucus for Art: Honor Awards for Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts (PDF). Women's Caucus for Art. p. 26. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- Parallel Visions: Selections from the Sylvia Sleigh Collection of Women Artists. New York: SOHO20 Gallery. 1999.

- Sherwin, Brian. "Art Space Talk: Sylvia Sleigh". myartspace>blog. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Artist, Curator & Critic Interviews: Sylvia Sleigh". !Women Art Revolution: Voices of a Movement. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- https://go.gale.com/ps/retrieve.do?tabID=News&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchResultsType=MultiTab&searchType=BasicSearchForm¤tPosition=1&docId=GALE%7CA149670098&docType=Brief+article&sort=Relevance&contentSegment=ZXAY-MOD1&prodId=OVIC&contentSet=GALE%7CA149670098&searchId=R1&userGroupName=los12365&inPS=true&ps=1&cp=1&prodId=OVIC

- Hottle, Andrew D. (2011). "Sylvia Sleigh: Artist and Collector". Groundbreaking: The Women of the Sylvia Sleigh Collection (PDF). Glassboro, NJ: Rowan University Art Gallery. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- "SYLVIA SLEIGH". www.sylviasleigh.com. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- "Finding Aid for the Sylvia Sleigh Papers, 1803-2011, bulk 1940-2000". hdl:10020/cifa2004m4. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Sylvia Sleigh, CV" (PDF). Feminist Art Base, Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement". College Art Association. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

External links

- 1 painting by or after Sylvia Sleigh at the Art UK site

- Lawrence Alloway and Sylvia Sleigh Correspondence, 1948–1982. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Approximately 1,000 digitized items from the archives of Sylvia Sleigh and Lawrence Alloway.

- Finding Aid for the Sylvia Sleigh Papers, 1803-2011, bulk 1940-2000. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession no. 2004.M.4. Archive contains more than 100 boxes of: correspondence; project files relating to exhibitions; documentation of artworks; writings and lectures; files relating to women artist organizations and cooperatives; teaching files; printed matter; and personal material.

- Sylvia Sleigh Papers, 1961-1983. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Files containing correspondence, printed material and miscellany; photographs of Sleigh's paintings; catalogs, announcements, and clippings concerning Sleigh.