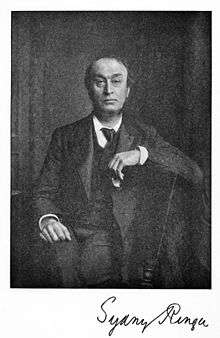

Sydney Ringer

Sydney Ringer FRS (March 1835 – 14 October 1910) was a British clinician, physiologist and pharmacologist, best known for inventing Ringer's solution. He was born in 1835 in Norwich, England and died following a stroke in 1910 in Lastingham, Yorkshire, England. His gravestone and some other records report 1835 for his birth, some census records and other documents suggest 1836, but his baptismal record at St Mary's Baptist Chapel (referred to in Ringer's own will) confirms this was 1835.

Life

Born into a non-conformist family (often, but incorrectly described as 'Quaker') in Norwich, Ringer's father died in 1843, while he was still very young. His elder brother, John Melancthon, amassed a vast fortune in Shanghai, and his younger brother, Frederick, went to Japan, where he founded the company Holme, Ringer & Co in Nagasaki and became so successful he was given the name "King of Nagasaki".

Ringer's entire professional career was associated with the University College Hospital, London. He entered University College in 1854 and graduated M.B. in 1860, being a resident medical officer in the University Medical Hospital from 1861 to 1862. He gained his M.D. in 1863 and that same year was appointed as assistant physician to the hospital, becoming a full physician in 1866.[1] From 1865 to 1869, he also held the position of assistant physician at the Children's Hospital, Great Ormond Street.

Ringer was an outstanding bedside teacher who continued the high standard of clinical instruction that had been established at the University College Hospital. He was not, however, in his element in set lectures. Ringer served successively as professor of materia medica, pharmacology and therapeutics, and the principles and practice of medicine at the University College faculty of medicine. In 1887, he was named Holme professor of clinical medicine, a chair he held until his retirement in 1900. In 1870 he became a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and in 1885 a Fellow of the Royal Society.[1]

Ringer's Handbook of Therapeutics was a classic of its day and passed through thirteen editions between 1869 and 1897. This book was originally commissioned as a revision of Jonathan Pereira's (1804–1853) massive Elements of Materia Medica (first edition from 1839), but Ringer was little concerned with the minutiae of traditional medical botany and materia medical. He offered instead a thoroughly practical treatise in which the actions and indications of drugs were concisely summarised.

Ringer was one of the early true clinical investigators. Patient care, clinical teaching, and writing occupied most of Ringer's career, but for many years he also maintained a small laboratory in the department of physiology; at that time there was no pharmacology laboratory at University College. He was universally known for his punctuality and the fanatical way he would spend every spare moment in his laboratory. It is even recorded that he climbed the palings of the hospital wall one evening when he found the door locked, to get to his laboratory. Following his morning round he would always make an appearance in the physiological laboratory and make suggestions to the laboratory assistant, examine the traces and then depart for his rooms at Cavendish Place, where he would do his consultant work.

With the aid of a series of collaborators, including E. G. A. Morshead, William Murrell (1853–1912), Harrington Sainsbury, and Dudley Buxton, Ringer published between 1875 and 1895 more than thirty papers devoted to the actions of inorganic salts on living tissues.

In the 1860s Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig had developed some perfusion techniques for the study of isolated organs. From the beginning the heart had served as the principal organ for these "extravital" investigations, and most of Ringer's physiological work relied on Ludwig's experimental model. In a classic series of experiments performed between 1882 and 1885, Ringer began with an isolated frog heart suspended in a 0.75% solution of sodium chloride. He then introduced additional substances (for example, blood and albumin) to the solution and observed the effects on the beating heart. He demonstrated that the abnormally prolonged ventricular dilation induced by pure sodium chloride solution is reversed by both blood and albumin. Ringer showed that small amounts of calcium in the perfusing solution are necessary for the maintenance of a normal heartbeat, a discovery he made after realising that instead of distilled water, his technician was actually using tap water containing (in London) calcium at nearly the same concentration as the blood. Ringer thus gradually perfected Ludwig's perfusion technique by proving that if small amounts of potassium are added to the normal solution of sodium chloride, isolated organs can be kept functional for long periods of time.

This formed the basis of Ringer's solution, which became an immediate necessity for the physiological laboratory. Clinically important derivatives include Ringer's lactate.

In 2007, a brief biography of Ringer[2] was published by the Physiological Society, of which Ringer was an early member.

References

- Rolleston 1912.

- A Solution for the Heart (free pdf)

Sources

- Dewolf, WC (1977). "Sydney Ringer (1835–1910)". Investigative Urology. 14 (6): 500–1. PMID 323186.

- Sternbach, George (1988). "Sydney ringer: Water supplied by the new river water company". Journal of Emergency Medicine. 6 (1): 71–4. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(88)90254-5. PMID 3283218.

- Fye, W B (1984). "Sydney Ringer, calcium, and cardiac function". Circulation. American Heart Association. 69 (4): 849–53. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.69.4.849. PMID 6365353.

- Lee, J. Alfred (1981). "Sydney Ringer (1834?1910) and Alexis Hartmann (1898?1964)". Anaesthesia. 36 (12): 1115–21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1981.tb08698.x. PMID 7034584.

- Miller, D. J. (2004). "Sydney Ringer; physiological saline, calcium and the contraction of the heart". The Journal of Physiology. 555 (Pt 3): 585–7. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.060731. PMC 1664856. PMID 14742734.

- Moore, Benjamin. "In Memory of Sidney Ringer [1835-1910]" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Obituary". The Lancet. 176 (4549): 1386–1387. 1910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)52779-2.

- Rolleston, Humphry Davy (1912). . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- "Sydney Ringer (1835-1910) Clinician and Pharmacologist". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 206 (11): 2515. 1968. doi:10.1001/jama.1968.03150110063015.

- Ellis, Harold (2010). "Sydney Ringer: Physician, physiologist and pharmacologist". British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 71 (11): 645. doi:10.12968/hmed.2010.71.11.79664. PMID 21063259.