Epinephrine (medication)

Epinephrine, also known as adrenaline, is a medication and hormone.[6][7] As a medication, it is used to treat a number of conditions, including anaphylaxis, cardiac arrest, asthma, and superficial bleeding.[4] Inhaled epinephrine may be used to improve the symptoms of croup.[8] It may also be used for asthma when other treatments are not effective.[4] It is given intravenously, by injection into a muscle, by inhalation, or by injection just under the skin.[4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | EpiPen, Adrenaclick, others |

| Other names | Epinephrine, adrenaline, adrenalin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603002 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Addiction liability | None |

| Routes of administration | IV, IM, endotracheal, IC, nasal, eye drop |

| ATC code | |

| Physiological data | |

| Receptors | Adrenergic receptors |

| Metabolism | Adrenergic synapse (MAO and COMT) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 15–20%[1][2] |

| Metabolism | Adrenergic synapse (MAO and COMT) |

| Metabolites | Metanephrine[3] |

| Onset of action | Rapid[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 2 minutes |

| Duration of action | Few minutes[5] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

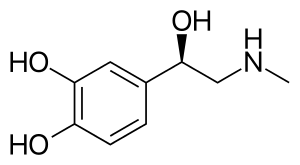

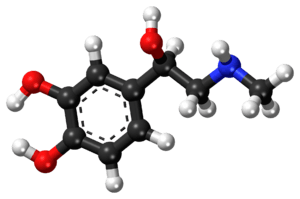

| Formula | C9H13NO3 |

| Molar mass | 183.207 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.283±0.06 g/cm3 @ 20 °C, 760 Torr |

| |

| |

Common side effects include shakiness, anxiety, and sweating.[4] A fast heart rate and high blood pressure may occur.[4] Occasionally, it may result in an abnormal heart rhythm.[4] While the safety of its use during pregnancy and breastfeeding is unclear, the benefits to the mother must be taken into account.[4]

Epinephrine is normally produced by both the adrenal glands and a small number of neurons in the brain where it acts as a neurotransmitter.[6][9] It plays an important role in the fight-or-flight response by increasing blood flow to muscles, output of the heart, pupil dilation, and blood sugar.[10][11] Epinephrine does this by its effects on alpha and beta receptors.[11] It is found in many animals and some one cell organisms.[12][13]

Jōkichi Takamine first isolated epinephrine in 1901 and it came into medical use in 1905.[14][15] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[16] It is available as a generic medication.[4] The wholesale cost in the developing world is between US$0.10 and US$0.95 a vial.[17] In the United States, the cost of the most commonly used autoinjector for anaphylaxis was about US$600 for two in 2016, while a generic version was about US$140 for two.[18] In Canada the wholesale cost of two cost is CA$190 as of 2019.[19] In 2017, it was the 263rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[20][21]

Medical uses

Epinephrine is used to treat a number of conditions including: cardiac arrest, anaphylaxis, and superficial bleeding.[22] It has been used historically for bronchospasm and low blood sugar, but newer treatments for these that are selective for β2 adrenoceptors, such as salbutamol are currently preferred.

Heart problems

While epinephrine is often used to treat cardiac arrest, it has not been shown to improve long-term survival or mental function after recovery.[23][24][25] It does, however, improve return of spontaneous circulation.[25] When used intravenously, epinephrine is typically given every three to five minutes.[26]

Epinephrine infusions may also be used for symptomatic bradycardia.[27]

Anaphylaxis

Epinephrine is the drug of choice for treating anaphylaxis. Different strengths, doses and routes of administration of epinephrine are used.

The commonly used epinephrine autoinjector delivers a 0.3 mg epinephrine injection (0.3 mL, 1:1000) and is indicated in the emergency treatment of allergic reactions including anaphylaxis to stings, contrast agents, medicines or people with a history of anaphylactic reactions to known triggers. A single dose is recommended for people who weigh 30 kg or more, repeated if necessary. A lower strength product is available for children.[28][29][30][31]

Intramuscular injection can be complicated in that the depth of subcutaneous fat varies and may result in subcutaneous injection, or may be injected intravenously in error, or the wrong strength used.[32] Intramuscular injection does give a faster and higher pharmacokinetic profile when compared to subcutaneous injection.[33]

Asthma

Epinephrine is also used as a bronchodilator for asthma if specific β2 agonists are unavailable or ineffective.[34]

When given by the subcutaneous or intramuscular routes for asthma, an appropriate dose is 0.3 to 0.5 mg.[35][36]

Because of the high intrinsic efficacy (receptor binding ability) of epinephrine, high concentrations of the drug cause negative side effects when treating asthma. The value of using nebulized epinephrine in acute asthma is unclear.[37]

Croup

Racemic epinephrine has historically been used for the treatment of croup.[38][39] Regular epinephrine however works equally well. Racemic adrenaline is a 1:1 mixture of the two isomers of adrenaline.[40] The L-form is the active component.[40] Racemic adrenaline works by stimulation of the alpha adrenergic receptors in the airway, with resultant mucosal vasoconstriction and decreased subglottic edema, and by stimulation of the β adrenergic receptors, with resultant relaxation of the bronchial smooth muscle.[39]

Bronchiolitis

There is a lack of consensus as to whether inhaled nebulized epiniphrine is beneficial in the treatment of bronchiolitis, with most guidelines recommending against its use.[41]

Local anesthetics

When epinephrine is mixed with local anesthetic, such as bupivacaine or lidocaine, and used for local anesthesia or intrathecal injection, it prolongs the numbing effect and motor block effect of the anesthetic by up to an hour.[42] Epinephrine is frequently combined with local anesthetic and can cause panic attacks.[43]

Epinephrine is mixed with cocaine to form Moffett's solution, used in nasal surgery.[44]

Adverse effects

Adverse reactions to adrenaline include palpitations, tachycardia, arrhythmia, anxiety, panic attack, headache, tremor, hypertension, and acute pulmonary edema. The use of epinephrine based eye-drops, commonly used to treat glaucoma, may also lead to buildup of adrenochrome pigments in the conjunctiva, iris, lens, and retina.

Rarely, exposure to medically administered epinephrine may cause Takotsubo cardiomyopathy.[45]

Use is contraindicated in people on nonselective β-blockers, because severe hypertension and even cerebral hemorrhage may result.[46]

Mechanism of action

| Organ | Effects |

|---|---|

| Heart | Increases heart rate; contractility; conduction across AV node |

| Lungs | Increases respiratory rate; bronchodilation |

| Liver | Stimulates glycogenolysis |

| Brain | |

| Systemic | Vasoconstriction and vasodilation |

| Triggers lipolysis | |

| Muscle contraction |

As a hormone, epinephrine acts on nearly all body tissues. Its actions vary by tissue type and tissue expression of adrenergic receptors. For example, high levels of epinephrine causes smooth muscle relaxation in the airways but causes contraction of the smooth muscle that lines most arterioles.

Epinephrine acts by binding to a variety of adrenergic receptors. Epinephrine is a nonselective agonist of all adrenergic receptors, including the major subtypes α1, α2, β1, β2, and β3.[46] Epinephrine's binding to these receptors triggers a number of metabolic changes. Binding to α-adrenergic receptors inhibits insulin secretion by the pancreas, stimulates glycogenolysis in the liver and muscle,[47] and stimulates glycolysis and inhibits insulin-mediated glycogenesis in muscle.[48][49] β adrenergic receptor binding triggers glucagon secretion in the pancreas, increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion by the pituitary gland, and increased lipolysis by adipose tissue. Together, these effects lead to increased blood glucose and fatty acids, providing substrates for energy production within cells throughout the body.[49] In the heart, the coronary arteries have a predominance of β2 receptors, which cause vasodilation of the coronary arteries in the presence of epinephrine.[50]

Its actions are to increase peripheral resistance via α1 receptor-dependent vasoconstriction and to increase cardiac output via its binding to β1 receptors. The goal of reducing peripheral circulation is to increase coronary and cerebral perfusion pressures and therefore increase oxygen exchange at the cellular level.[51] While epinephrine does increase aortic, cerebral, and carotid circulation pressure, it lowers carotid blood flow and end-tidal CO2 or ETCO2 levels. It appears that epinephrine may be improving macrocirculation at the expense of the capillary beds where actual perfusion is taking place.[52]

History

Extracts of the adrenal gland were first obtained by Polish physiologist Napoleon Cybulski in 1895. These extracts, which he called nadnerczyna, contained adrenaline and other catecholamines.[53] American ophthalmologist William H. Bates discovered adrenaline's usage for eye surgeries prior to 20 April 1896.[54] Japanese chemist Jōkichi Takamine and his assistant Keizo Uenaka independently discovered adrenaline in 1900.[55][56] In 1901, Takamine successfully isolated and purified the hormone from the adrenal glands of sheep and oxen.[57] Adrenaline was first synthesized in the laboratory by Friedrich Stolz and Henry Drysdale Dakin, independently, in 1904.[56]

Society and culture

Cost

The wholesale cost of epinephrine in the developing world is between US$0.10 and US$0.95 a vial.[17] In the United States, the cost of the most commonly used autoinjector for anaphylaxis was about US$600 for two in 2016, while a generic version was about US$140 for two.[18] In Canada the wholesale cost of two cost is CA$190 as of 2019.[19]

Brand names

Common brand names include Asthmanefrin, Micronefrin, Nephron, VapoNefrin, and Primatene Mist.

Delivery forms

Epinephrine is available in an autoinjector delivery system.

There is an epinephrine metered-dose inhaler sold over-the-counter in the United States for the relief of bronchial asthma.[58][59] It was introduced in 1963 by Armstrong Pharmaceuticals.[60]

A common concentration for epinephrine is 2.25% w/v epinephrine in solution, which contains 22.5 mg/mL, while a 1% solution is typically used for aerosolization.

References

- El-Bahr, S. M.; Kahlbacher, H.; Patzl, M.; Palme, R. G. (2006). "Binding and Clearance of Radioactive Adrenaline and Noradrenaline in Sheep Blood". Veterinary Research Communications. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 30 (4): 423–432. doi:10.1007/s11259-006-3244-1. ISSN 0165-7380. PMID 16502110.

- Franksson, Gunhild; Änggård, Erik (2009-03-13). "The Plasma Protein Binding of Amphetamine, Catecholamines and Related Compounds". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. Wiley. 28 (3): 209–214. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1970.tb00546.x. ISSN 0001-6683.

- Peaston, R. T; Weinkove, C. (2004-01-01). "Measurement of catecholamines and their metabolites". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. SAGE Publications. 41 (1): 17–38. doi:10.1258/000456304322664663. ISSN 0004-5632.

- "Epinephrine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-09-06. Retrieved Aug 15, 2015.

- Nancy Caroline's emergency care in the streets (7th ed.). [S.l.]: Jones And Bartlett Learning. 2012. p. 557. ISBN 9781449645861. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Lieberman M, Marks A, Peet A (2013). Marks' Basic Medical Biochemistry: A Clinical Approach (4 ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 175. ISBN 9781608315727. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- "(-)-adrenaline". Guide to Pharmacology. IUPS/BPS. Archived from the original on 1 September 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- Everard ML (February 2009). "Acute bronchiolitis and croup". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 56 (1): 119–33, x–xi. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2008.10.007. PMID 19135584.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 157. ISBN 9780071481274.

Epinephrine occurs in only a small number of central neurons, all located in the medulla. Epinephrine is involved in visceral functions, such as the control of respiration. It is also produced by the adrenal medulla.

- Bell DR (2009). Medical physiology : principles for clinical medicine (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 312. ISBN 9780781768528. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Khurana (2008). Essentials of Medical Physiology. Elsevier India. p. 460. ISBN 9788131215661. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Buckley E (2013). Venomous Animals and Their Venoms: Venomous Vertebrates. Elsevier. p. 478. ISBN 9781483262888. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Animal Physiology: Adaptation and Environment (5 ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1997. p. 510. ISBN 9781107268500. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Wermuth CG (2008). The practice of medicinal chemistry (3 ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780080568775. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 541. ISBN 9783527607495.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Epinephrine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Ginger Skinner (August 11, 2016). "Can You Get A Cheaper EpiPen?". Consumer Reports. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016.

- "[119] Epinephrine autoinjectors available in Canada". Therapeutics Initiative. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Epinephrine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Epinephrine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Kempton, H (11 January 2019). "Standard dose epinephrine versus placebo in out of hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 37 (3): 511–517. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.12.055. PMID 30658877.

- Reardon PM, Magee K (2013). "Epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A critical review". World Journal of Emergency Medicine. 4 (2): 85–91. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2013.02.001. PMC 4129833. PMID 25215099.

- Lin S, Callaway CW, Shah PS, Wagner JD, Beyene J, Ziegler CP, Morrison LJ (June 2014). "Adrenaline for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Resuscitation. 85 (6): 732–40. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.03.008. PMID 24642404.

- Mark S, Link; Lauren C, Berkow; Peter J, Kudenchuk (2015). "Part 7: Adult Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support - Figures and Tables". Circulation. 132 (18 suppl 2): S444–S464. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000261. PMID 26472995.

- "Part 6: Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support Section 6: Pharmacology II: Agents to Optimize Cardiac Output and Blood Pressure". Circulation. 102 (Supp 1): I–129–I–135. 2000. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.102.suppl_1.I-129.

- Mylan Specialty L.P. "EPIPEN®- epinephrine injection, EPIPEN Jr®- epinephrine injection" (PDF). FDA Product Label. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ECC Committee, Subcommittees and Task Forces of the American Heart Association (2005). "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 10.6: Anaphylaxis". Circulation. 112 (24 suppl): IV–143–IV–145. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.105.166568.

- Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, Kudenchuk PJ, Ornato JP, McNally B, Silvers SM, Passman RS, White RD, Hess EP, Tang W, Davis D, Sinz E, Morrison LJ (November 2010). "Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S729–67. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. PMID 20956224.

- Lieberman P, Nicklas RA, Oppenheimer J, Kemp SF, Lang DM, Bernstein DI, et al. (September 2010). "The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis practice parameter: 2010 update". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 126 (3): 477–80.e1–42. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.022. PMID 20692689.

- Pennsylvania Patient Advisory. "Let's Stop this "Epi"demic!—Preventing Errors with Epinephrine". Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- McLean-Tooke AP, Bethune CA, Fay AC, Spickett GP (December 2003). "Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence?". BMJ. 327 (7427): 1332–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1332. PMC 286326. PMID 14656845.

- Koninckx M, Buysse C, de Hoog M (June 2013). "Management of status asthmaticus in children". Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 14 (2): 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2013.03.003. PMID 23578933.

- Soar, Perkins, et al (2010) European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation. Oct. pp.1400–1433

- Fisher, Brown, Cooke (Eds) (2006) Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee. UK Ambulance Clinical Practice Guidelines.

- Abroug F, Dachraoui F, Ouanes-Besbes L (March 2016). "Our paper 20 years later: the unfulfilled promises of nebulised adrenaline in acute severe asthma". Intensive Care Medicine. 42 (3): 429–31. doi:10.1007/s00134-016-4210-1. PMID 26825950.

- Bjornson CL, Johnson DW (January 2008). "Croup". Lancet. 371 (9609): 329–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60170-1. PMC 7138055. PMID 18295000.

- Thomas LP, Friedland LR (January 1998). "The cost-effective use of nebulized racemic epinephrine in the treatment of croup". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 16 (1): 87–9. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(98)90073-0. PMID 9451322.

- Malhotra A, Krilov LR (January 2001). "Viral croup". Pediatrics in Review. 22 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1542/pir.22-1-5. PMID 11139641.

- Kirolos A, Manti S, Blacow R, Tse G, Wilson T, Lister M, Cunningham S, Campbell A, Nair H, Reeves RM, Fernandes RM, Campbell H (August 2019). "A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis". J. Infect. Dis. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz240. PMID 31541233.

- Tschopp C, Tramèr MR, Schneider A, Zaarour M, Elia N (July 2018). "Benefit and Harm of Adding Epinephrine to a Local Anesthetic for Neuraxial and Locoregional Anesthesia: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials With Trial Sequential Analyses" (PDF). Anesth. Analg. 127 (1): 228–239. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000003417. PMID 29782398.

- Rahn R, Ball B (2001). Local Anesthesia in Dentistry: Articaine and Epinephrine for Dental Anesthesia (1 st ed.). Seefeld, Germany: 3M ESPE. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-00-008562-8.

- Benjamin E, Wong DK, Choa D (December 2004). "'Moffett's' solution: a review of the evidence and scientific basis for the topical preparation of the nose". Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences. 29 (6): 582–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00894.x. PMID 15533141.

- Nazir S, Lohani S, Tachamo N, Ghimire S, Poudel DR, Donato A (February 2017). "Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with epinephrine use: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Int. J. Cardiol. 229: 67–70. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.266. PMID 27889211.

- Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-59541-101-3.

- Arnall DA, Marker JC, Conlee RK, Winder WW (June 1986). "Effect of infusing epinephrine on liver and muscle glycogenolysis during exercise in rats". The American Journal of Physiology. 250 (6 Pt 1): E641–9. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1986.250.6.E641. PMID 3521311.

- Raz I, Katz A, Spencer MK (March 1991). "Epinephrine inhibits insulin-mediated glycogenesis but enhances glycolysis in human skeletal muscle". The American Journal of Physiology. 260 (3 Pt 1): E430–5. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.1991.260.3.E430. PMID 1900669.

- Sabyasachi Sircar (2007). Medical Physiology. Thieme Publishing Group. p. 536. ISBN 978-3-13-144061-7.

- Sun D, Huang A, Mital S, Kichuk MR, Marboe CC, Addonizio LJ, Michler RE, Koller A, Hintze TH, Kaley G (July 2002). "Norepinephrine elicits beta2-receptor-mediated dilation of isolated human coronary arterioles". Circulation. 106 (5): 550–5. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000023896.70583.9F. PMID 12147535.

- "Guideline 11.5: Medications in Adult Cardiac Arrest" (PDF). Australian Resuscitation Council. December 2010. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Burnett AM, Segal N, Salzman JG, McKnite MS, Frascone RJ (August 2012). "Potential negative effects of epinephrine on carotid blood flow and ETCO2 during active compression-decompression CPR utilizing an impedance threshold device". Resuscitation. 83 (8): 1021–4. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.03.018. PMID 22445865.

- Skalski JH, Kuch J (April 2006). "Polish thread in the history of circulatory physiology". Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 57 (Suppl 1): 5–41. PMID 16766800. Archived from the original on 2011-03-10.

- Bates WH (16 May 1896). "The Use of Extract of Suprarenal Capsule in the Eye". New York Medical Journal: 647–650. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- Yamashima T (May 2003). "Jokichi Takamine (1854-1922), the samurai chemist, and his work on adrenalin". Journal of Medical Biography. 11 (2): 95–102. doi:10.1177/096777200301100211. PMID 12717538.

- Bennett MR (June 1999). "One hundred years of adrenaline: the discovery of autoreceptors". Clinical Autonomic Research. 9 (3): 145–59. doi:10.1007/BF02281628. PMID 10454061.

- Takamine J (1901). The isolation of the active principle of the suprarenal gland. The Journal of Physiology. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxix–xxx.

- "Background". Armstrong Pharmaceuticals. Archived from the original on 2013-09-13. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- "Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., and Janet Woodcock, M.D., director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, on approval of OTC Primatene Mist to treat mild asthma". FDA archive.

- "Frequent Asked Questions". Armstrong Pharmaceuticals. Archived from the original on 2011-09-25. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

Primatene® Mist was launched in 1963. The Primatene® Mist brand has built a long-time heritage for over-the-counter relief of bronchial asthma.

- Wiebe K, Rowe BH (July 2007). "Nebulized racemic epinephrine used in the treatment of severe asthmatic exacerbation: a case report and literature review". Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 9 (4): 304–8. doi:10.1017/s1481803500015220. PMID 17626698.

- Davies MW, Davis PG (2002). "Nebulized racemic epinephrine for extubation of newborn infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD000506. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000506. PMC 7038644. PMID 11869578.

External links

- "Epinephrine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.