Supporting hyperplane

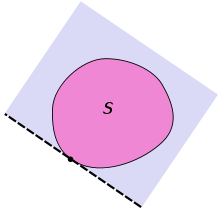

In geometry, a supporting hyperplane of a set in Euclidean space is a hyperplane that has both of the following two properties:[1]

- is entirely contained in one of the two closed half-spaces bounded by the hyperplane,

- has at least one boundary-point on the hyperplane.

Here, a closed half-space is the half-space that includes the points within the hyperplane.

Supporting hyperplane theorem

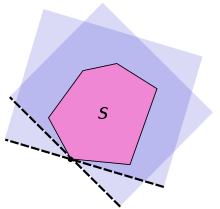

This theorem states that if is a convex set in the topological vector space and is a point on the boundary of then there exists a supporting hyperplane containing If ( is the dual space of , is a nonzero linear functional) such that for all , then

defines a supporting hyperplane.[2]

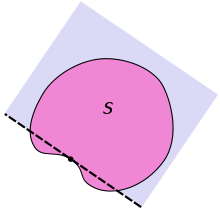

Conversely, if is a closed set with nonempty interior such that every point on the boundary has a supporting hyperplane, then is a convex set.[2]

The hyperplane in the theorem may not be unique, as noticed in the second picture on the right. If the closed set is not convex, the statement of the theorem is not true at all points on the boundary of as illustrated in the third picture on the right.

The supporting hyperplanes of convex sets are also called tac-planes or tac-hyperplanes.[3]

A related result is the separating hyperplane theorem, that every two disjoint convex sets can be separated by a hyperplane.

See also

- Support function

- Supporting line (supporting hyperplanes in )

Notes

- Luenberger, David G. (1969). Optimization by Vector Space Methods. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-471-18117-0.

- Boyd, Stephen P.; Vandenberghe, Lieven (2004). Convex Optimization (pdf). Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-521-83378-3. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- Cassels, John W. S. (1997), An Introduction to the Geometry of Numbers, Springer Classics in Mathematics (reprint of 1959[3] and 1971 Springer-Verlag ed.), Springer-Verlag.

References & further reading

- Ostaszewski, Adam (1990). Advanced mathematical methods. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-521-28964-5.

- Giaquinta, Mariano; Hildebrandt, Stefan (1996). Calculus of variations. Berlin; New York: Springer. p. 57. ISBN 3-540-50625-X.

- Goh, C. J.; Yang, X.Q. (2002). Duality in optimization and variational inequalities. London; New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 13. ISBN 0-415-27479-6.