Supervisory control

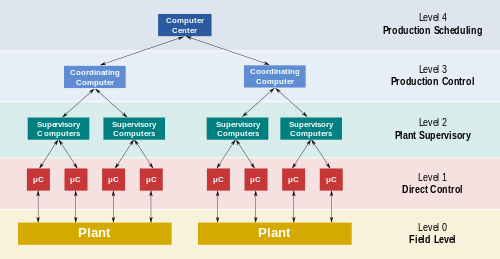

Supervisory control is a general term for control of many individual controllers or control loops, such as within a distributed control system. It refers to a high level of overall monitoring of individual process controllers, which is not necessary for the operation of each controller, but gives the operator an overall plant process view, and allows integration of operation between controllers.

A more specific use of the term is for a Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition system or SCADA, which refers to a specific class of system for use in process control, often on fairly small and remote applications such as a pipeline transport, water distribution, or wastewater utility system station.

Forms

Supervisory control often takes one of two forms. In one, the controlled machine or process continues autonomously. It is observed from time to time by a human who, when deeming it necessary, intervenes to modify the control algorithm in some way. In the other, the process accepts an instruction, carries it out autonomously, reports the results and awaits further commands. With manual control, the operator interacts directly with a controlled process or task using switches, levers, screws, valves etc., to control actuators. This concept was incorporated in the earliest machines which sought to extend the physical capabilities of man. In contrast, with automatic control, the machine adapts to changing circumstances and makes decisions in pursuit of some goal which can be as simple as switching a heating system on and off to maintain a room temperature within a specified range. Sheridan [1] defines supervisory control as follows: "in the strictest sense, supervisory control means that one or more human operators are intermittently programming and continually receiving information from a computer that itself closes an autonomous control loop through artificial effectors to the controlled process or task environment."

Other points

Robotics applications have traditionally aimed for automatic control. Automatic control requires sensing and responding appropriately to all combinations of circumstances which can present problems of overwhelming complexity. A supervisory control scheme offers the prospect of solving the automation problem incrementally and leaving those problems unsolved to be handled by the human supervisor.

Communications delay does not have the same impact on this control scheme. All time critical feedback occurs at the slave where the delays are negligible. Instability is thus avoided without modifying the feedback loop. Communications delay, in this case, slows the rate at which an operator can assign tasks to the slave and determine whether those tasks have been successfully carried out.

See also

- Human reliability and human factors for more on human supervisory control

- Thomas B. Sheridan, a researcher of supervisory control and other subjects and professor of mechanical engineering at MIT

- Supervisory control theory

References: Human Supervisory Control

- Amalberti, R. and Deblon, F (1992). Cognitive Modelling of Fighter Aircraft Process Control: A Step Towards an Intelligent On-Board Assistance System. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 36, 639-671.

- Hollnagel, E., Mancini, G. and Woods, D. (Eds.) (1986). Intelligent decision support in process environments. New York: Academic Press.

- Jones, P. M. and Jasek, C. A. (1997). Intelligent support for activity management (ISAM): An architecture to support distributed supervisory control. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Special issue on Human Interaction in Complex Systems, Vol. 27, No. 3, May 1997, 274-288.

- Jones, P. M. and Mitchell, C. M. (1995). Human-computer cooperative problem solving: Theory, design, and evaluation of an intelligent associate system for supervisory control. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 25, 7, July 1995, 1039-1053.

- Mailin, J. T., Schreckenghost, D. L., Woods, D. D., Potter, S. S., Johannsen, L., Holloway, M. and Forbus, K. D. (1991). Making intelligent systems team players: Case studies and design issues. Volume 1: Human-computer interaction design. NASA Technical Memorandum 104738, NASA Johnson Space Center.

- Mitchell, C. M. (1999). Model-based design of human interaction with complex systems. In A. P. Sage and W. B. Rouse (Eds.), Handbook of systems engineering and management (pp. 745 – 810). Wiley.

- Rasmussen, J., Pejtersen, A. and Goodstein, L. (1994). Cognitive systems engineering. New York: Wiley.

- Sarter, N. and Amalberti, R. (Eds.) (2000). Cognitive engineering in the aviation domain. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Sheridan, T. B. (1992). Telerobotics, automation, and human supervisory control. MIT Press.

- Sheridan, T. B. (2002). Humans and automation: System design and research issues. Wiley.

- Sheridan, T. B. (Ed.) (1976). Monitoring behavior and supervisory control. Springer.

- Woods, D. D. and Roth, E. M. (1988). Cognitive engineering: Human problem solving with tools. Human Factors, 30, 4, 415-430.

Citations

- Sheridan, Thomas B. (1992). Telerobotics, Automation, and Human Supervisory Control. MIT Press, Cambridge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-262-19316-0.