Sumner, New Zealand

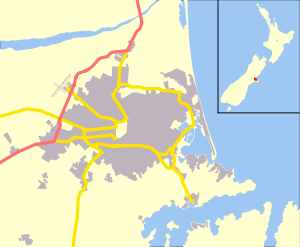

Sumner is a coastal seaside suburb of Christchurch, New Zealand and was surveyed and named in 1849 in honour of John Bird Sumner, the then newly appointed Archbishop of Canterbury and president of the Canterbury Association. Originally a separate borough, it was amalgamated with the city of Christchurch as communications improved and the economies of scale made small town boroughs uneconomic to operate.

Sumner | |

|---|---|

Looking down on Sumner (left) from Scarborough | |

Sumner | |

| Coordinates: 43.57144°S 172.76447°E | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.3178 km2 (3.5976 sq mi) |

| Population (2006) | |

| • Total | 3,978 |

| • Density | 430/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

History

.jpg)

The Māori name for the area is Ohikaparuparu ("o" means place of; "hika" means rubbing, kindling, or planting; "paruparu" means dirt, deeply laden, or a preparation of fermented cockles).[1]

Sumner was surveyed in 1849 by Edward Jollie for Captain Joseph Thomas, the advanced agent of the Canterbury Association. His map showed 527 sections and numerous reserved and provisions for churches, schools, cemeteries, town hall, emigration barracks and other town amenities. However, his plans were abandoned through lack of funds and a new survey on which Sumner is based was carried out in 1860.

Captain Thomas named the settlement for Bishop John Bird Sumner, one of the leading members of the Canterbury Association.

Sumner was at first under the control of the Canterbury Provincial Council.

The first European to carry out work in Sumner is believed to be Charles Crawford, a whaleboat owner, who transported materials from Port Cooper, now Lyttelton, under contract to build the headquarters and storeroom for Captain Thomas. Sumner was settled in late 1849 or early 1850 by work crews building the road to Lyttelton, Sumner is thus one of the oldest European settlements in the Christchurch area. The Day family was the first to settle permanently in Sumner followed by Edward Dobson and his family.

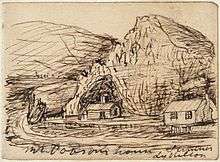

In December 1854, Commander Byron Drury, in HMS Pandora, surveyed the Sumner Bay, including the bar and mouth of the Avon-Heathcote Estuary for the Canterbury Provincial Council. Drury wrote a report and produced a detailed chart of the area, with soundings.[2] Commander Drury's 1854 chart locates several buildings on shore, including a store at the foot of the hill in Clifton Bay, Day's house, which is set well back from the foreshore on a bend in the road, as it turns away from the foot of Clifton hill, and Dobson's house, which is shown at end of the spur at the foot of Richmond Hill. Compared to a modern-day map, the Day's house would have been near the corner at the top end of Nayland Street while Dobson's house would be near the intersection of Nayland Street and Wakefield Avenue.

Sumner had its first shop early in 1870, and its proprietor, S.E. Horneman, was postmaster from 1873 until 1876.

In 1872, it came under the control of the Heathcote Road District. When provincial councils were disestablished in 1876 and replaced with counties, Sumner had a second parent body, the Selwyn County added to the continuing road board.[3] In 1883, Sumner was constituted as a town district and was run by a board of five elected commissioners.[4] The board elected its own chairmen, and the two people who filled that role were C. L. Wiggins (March 1883 – September 1884) and J. M. Wheeler (September 1884 – June 1891).[5] On 1 June 1891, Sumner was proclaimed a borough.[6] Mayoral elections were held on 27 June, and the last chairman was elected the first Mayor of Sumner.[7]

In 1885 the Harbour Board granted the concession to build a bath at the East end of Sumner beach. S.L. Bell enclosed some of the sea, built dressing sheds and a tea shop. The bathing pool was a great attraction but every year terrific storms would batter the bath and gradually dump fine sand. Eventually a flood filled the bath with clay and silt from the hills causing its closure.

In 1912 Sumner established its own gasworks and electricity was connected in 1918.[8] The Anglican evangelical leader William Orange was vicar of Sumner from 1930–1945.[9]

On 22 February 2011, Sumner was hit by the Christchurch earthquake, which destroyed or made uninhabitable a large number of the local houses and commercial buildings. On 13 June the same year, Sumner was hit by another earthquake of almost the same magnitude as the February event. These two earthquakes caused many of Sumner's iconic cliffs to collapse, and many areas to be cordoned off with both traditional fences and shipping containers.

Geography

Sumner is nestled in a coastal valley separated from the adjacent city suburbs by rugged volcanic hill ridges that end in cliffs that descend to the sea shore in places. Sumner Bay is the first bay on the northern side of Banks Peninsula and faces Pegasus Bay and the Pacific Ocean.

Because of its ocean exposure, a high surf can form in some swell conditions. The beach is gently sloping, with fine grey sand. It is a popular surf beach for these reasons.

Sand dunes have filled the river valley behind the beach. This has made housing construction relatively easy, although flooding at the head of the valley has been a problem in the past due to the reverse slope caused by the sand dunes filling the front of the valley. This has been addressed by a flood drain.

The rocky volcanic outcrop of Cave Rock dominates the beach. Until the mid-1860s, the feature was known as Cass Rock, after the surveyor Thomas Cass.[10] There are other rocky outcrops in the area and the volcanic nature of the geology is readily apparent from several of the exposed cliffs around the valley.

A sea wall and wide esplanade have been built along the length of the beach to prevent coastal erosion.

Sumner bar

The outlet of the Avon Heathcote Estuary at the western end of the beach, near another large volcanic outcrop known as Shag Rock, or Rapanui, forms the Sumner bar off shore of Cave Rock. The Sumner bar presents a major hazard to shipping, while the fast currents, strong rips and undertows in the area can be a danger to swimmers.

The Sumner Bar is a sand bar where the estuary meets the sea and is notoriously dangerous to cross. One regular vessel crossing the bar in the early days was the Mullogh, New Zealand's first iron hulled steamer. On 25 August 1865 the Mullogh ran onto Cave Rock, Sumner, in violent surf. Her cargo of liquor created keen interest on the beach. George Holmes of Pigeon Bay, the contractor for the Lyttelton Rail Tunnel, then bought the ship, refitted and used her until 1869.[11]

The NZ Trawler Muriel was stranded on Sumner Beach in 1937 and was a total loss and had to be dismantled where she lay.

Education

Sumner School

Sumner School was founded in 1876 and is these days a full primary school, teaching children from years 1 to 8. The school has, as of 2011, a roll of 435 pupils and is decile 10.[12][13]

Star of the Sea School

The Star of the Sea School is a Catholic full primary school, teaching children from years 1 to 8. In 2011, the school has a roll of 121 pupils and is decile 10.[14][15]

van Asch Deaf Education Centre

The van Asch Deaf Education Centre takes hearing-impaired children from all over the South Island and the southern North Island. Apart from the Sumner campus, it operates satellite classrooms at Sumner School and at Linwood High School. In 2011, the school has a roll of 28 pupils and is decile 4.[16][17]

Sumner Life Boat Institution

Because of the hazard posed by the Sumner Bar, Sumner has had a lifeboat of some kind almost since its settlement. There is no record of a formal or even informal lifeboat being available prior to the appointment of a pilot in September 1864. However, it is likely that small open rowing boats were available in the bay from the early 1850s.

The Sumner Life Boat Institution has operated a formal life boat or similar rescue craft in the bay since 1898. The traditional name of Rescue has been applied to many of the life boats.

Notes

- Reed, A. W. (2010). Peter Dowling (ed.). Place Names of New Zealand. Rosedale, North Shore: Raupo. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-14-320410-7.

- Amodeo, Colin (1998). Rescue: The Sumner community and its lifeboat. Sumner, Christchurch, New Zealand: Sumner Lifeboat Institution Incorporated. p. 2. ISBN 0 473 05164 8.

- Menzies 1941, p. 17.

- Menzies 1941, p. 19.

- Menzies 1941, p. 20.

- Menzies 1941, p. 30.

- Menzies 1941, pp. 30–31.

- de Their, Walter (1976). Sumner to Ferrymead, a Christchurch History. Pegasus Press, Christchurch. pp. 19–54. ISBN 1-877151-04-1.

- Clark, Jeremy J. "William Alfred Orange". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Harper, Margaret. "Christchurch Place Names: A-M" (PDF). Christchurch City Libraries. pp. 52–53. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- "The single screw Iron steam ship Mullogh of 1855". New Zealand Maritime Record. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "About Us". Sumner School. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "Sumner School". Te Kete Ipurangi. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "Welcome". Our Lady Star of the Sea School. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "Star of the Sea School". Te Kete Ipurangi. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "van Asch Deaf Education Centre, Christchurch, New Zealand". van Asch Deaf Education Centre. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- "Van Asch Deaf Education Centre". Te Kete Ipurangi. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sumner, New Zealand. |

- Menzies, J. F. (1941). Sumner (PDF). Christchurch: Simpson & Williams Ltd. Retrieved 31 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)