Shuka

Shuka[1][2] (Sanskrit: शुक IAST: Śuka, also Shukadeva शुकदेव Śuka-deva, Shuka deva, Suka, Sukadev, Śukadeva Gosvāmī) was the son of the sage Vyasa (credited as the organizer of the Vedas and Puranas) and the main narrator of the Bhagavata Purana. Most of the Bhagavata Purana consists of Shuka reciting the story to the dying king Parikshit. Shuka is depicted as a sannyasi, renouncing the world in pursuit of moksha (liberation), which most narratives assert that he achieved.[3]

| Shuka | |

|---|---|

| Mahabharata character | |

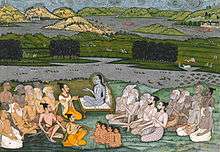

Shuka preaching to sages | |

| In-universe information | |

| Family | Vyasa (father) Pinjalaa (mother) |

| Spouse | Pivari |

According to the Mahabharata, after one hundred years of austerity by Vyasa, Shuka was churned out of a stick of fire, born with ascetic power and with the Vedas dwelling inside him, just like his father.

A slight different story is told in other scriptures. One day goddess Parvati asks Lord Shiva about the garland of skulls he always wears, asking whose skulls was it, and Lord Shiva replies that it is all the previous births of Parvati and he wears her skulls after she dies, as a momento of her. Surprised, Parvati asks why only she dies and not the lord with her? Lord Shiva says that he knows the secret of Amaratwa (immortality). Parvati requests the lord to tell her the secret of immortality. Lord Shiva shakes his damru so that every living being in the area leaves the place, so that the secret does not slip out to them. The lord says that he would close his eyes and recite the secret in a story form and she should make “hmm” sound so that he knows that she is listening. Nearby, there was an egg of a parrot on the verge of cracking, and when the parrot comes out, he too becomes the listener of the story, but no one knows that he was there. The story is started and Parvati makes the sound, but mid-way falls asleep. The parrot, however, continues to make the “hmm” sound and so the lord does not stop. Once the story is over, he finds that Parvati is asleep and that someone else eavesdropped and heard the secret. He notices the parrot and chases to kill him.

The tiny parrot flies into a nearby forest and enters into the womb of Vyasa’s wife through her mouth, when she was yawning. The lord arrives and demand that the parrot comes out, but Vyasa persuades to leave the parrot as if he truly knew the secret, it was no use killing it as it will be still alive just like Rahu. Then Vyasa asks the parrot to come out, but it refuses, stating that if he comes out, he will be termed as Vyasa’s son and he does not want any attachment, and only want moksha. This continues for 12 years and it makes Vyasa’s wife bear the pain, as the parrot is growing in her womb as a child for all those years. Vyasa prays to Lord Vishnu to help his wife. Lord Vishnu, who was present on the earth as Krishna, arrives. Krishna assures the parrot that no one would kill him and he would be incapable of attachment and eligible for moksha. The parrot then comes out in a human form and is named “Shuka” (Sanskrit for “parrot”).

The Mahabharata also recounts how Shuka was sent by Vyasa for training to King Janaka, who was considered to be a Jivanmukta or one who is liberated while still in a body. Shuka studied under Brihaspati and his own father, Vyasa. Shuka asked Janaka about the way to liberation, with Janaka recommending the traditional progression of the four ashramas, which included the householder stage. After expressing contempt for the householder life, Shuka questioned Janaka about the real need for following the householder path. Seeing Shuka's advanced state of realization, Janaka told him that there was no need in his case.[4]

Stories recount how Shuka surpassed his father in spiritual attainment. Once, when following his son, Vyasa encountered a group of celestial nymphs who were bathing. Shuka's purity was such that the nymphs did not consider him to be a distraction, even though he was naked, but covered themselves when faced with his father.[5][6] Shuka is sometimes portrayed as wandering about naked, due to his complete lack of self-consciousness.[7]

A completely different version of the later life of Shuka is given in the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, considered a secondary Purana (upapurana) by many, but an important work in the Shakta tradition. In this account, Shuka is convinced by Janaka to follow the ashrama tradition and returns home to marry and follow the path of yoga. He has five children with his wife Pivari—four sons and a daughter. The story concludes in the same vein as the common tradition, with Shuka achieving moksha.[8]

A place called Shukachari is believed to be the cave of Shuka, where he disappeared in cave stones as per local traditions. Shuka in Sanskrit means parrot and thus the name is derived from the large number of parrots found around the Shukachari hills. Shukachari literally means abode of parrots in the Sanskrit language.

See also

Further reading

- Shuka. In: Wilfried Huchzermeyer: Studies in the Mahabharata. Indian Culture, Dharma and Spirituality in the Great Epic. Karlsruhe 2018, ISBN 978-3-931172-32-9, pp. 164-178

Shuka. Being a Holy saint and having a distinction of founding Srimad Bhagavatam in the present elaborated form as received from Lord Veda Vyasa is the main Guru. Hence, is called as Sri Shukacharya or Shuka Muni with reverence. The Mangalacharan or the first verse of prayer to start Srimad Bhagavatam is offered to Sri Shukacharya in the Uttara Khanda of Padma Purana called The Glory and the Procedure to hear Srimad Bhagavatam immediately after that of Lord. Starting with Uttara Khand of Padma Purana has been a tradition. Here, Sri Shukacharya has been described as having the dominant attribute of dispassion to materialistic things including his body. Sri Madhvacharya has concluded Sri Shukachary as an incarnation of Rudra. Sri Shukacharya always appears as sixteen years old.

References

- Matchett, Freda (2001). Krishna, Lord or Avatara?: the relationship between Krishna and Vishnu. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2001). Rethinking the Mahābhārata: a reader's guide to the education of the dharma king. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-34054-8.

- Sullivan, Bruce M. (1990). Kṛṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vyāsa and the Mahābhārata: a new interpretation. BRILL. p. 40. ISBN 978-90-04-08898-6.

- Gier, Nicholas F. (2000). Spiritual Titanism: Indian, Chinese, and Western perspectives. SUNY series in constructive postmodern thought. SUNY Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-7914-4527-3.

- Venkatesananda, S. (1989). The Concise Srimad Bhagavatam. State University of New York Press.

- Purdy, S.B. (2006). "Whitman and the (National) Epic: a Sanskrit Parallel". Revue Francaise d Etudes Americaines. 108 (2006/2): 23–32. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- Prabhavananda, Swami (1979) [1962]. Spiritual Heritage of India. Vedanta Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-87481-035-6.

- Fort, Andrew O.; Patricia Y. Mumme (1996). Living liberation in Hindu thought. SUNY Press. pp. 170–173. ISBN 978-0-7914-2705-7.