Church of the SubGenius

The Church of the SubGenius is a parody religion[1] that satirizes better-known belief systems. It teaches a complex philosophy that focuses on J. R. "Bob" Dobbs, purportedly a salesman from the 1950s, who is revered as a prophet by the Church. SubGenius leaders have developed detailed narratives about Dobbs and his relationship to various gods and conspiracies. Their central deity, Jehovah 1, is accompanied by other gods drawn from ancient myth and popular fiction. SubGenius literature describes a grand conspiracy that seeks to brainwash the world and oppress Dobbs's followers. In its narratives, the Church presents a blend of cultural references in an elaborate remix of the sources.

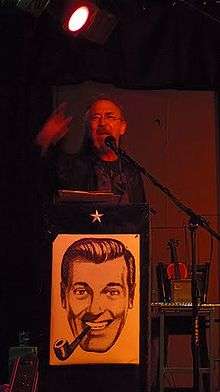

Ivan Stang, who co-founded the Church in the 1970s, serves as its leader and publicist. He has imitated actions of other religious leaders, using the tactic of culture jamming in an attempt to undermine better-known faiths. Church leaders instruct their followers to avoid mainstream commercialism and the belief in absolute truths. The group holds that the quality of "Slack" is of utmost importance, but it is never clearly defined. The number of followers is unknown, although the Church's message has been welcomed by college students and artists in the United States. The group is often compared to Discordianism. Journalists often consider the Church an elaborate joke, but some academics have defended it as a real system of deeply held beliefs.[2][3]

Origins

The Church of the SubGenius was founded by Ivan Stang (born Douglas St Clair Smith) and Philo Drummond (born Steve Wilcox)[4] as the SubGenius Foundation.[5] Dr. X (born Monte Dhooge) was also present at the group's inception.[6] The organization's first recorded activity was the publication of a photocopied document, Sub Genius Pamphlet #1, disseminated in Dallas, Texas in 1979. The document announced the impending end of the world and the possible deaths of its readers.[5] It criticized Christian conceptions of God and New Age perceptions of spirituality.[7]

Church leaders maintain that a man named J. R. "Bob" Dobbs founded the group in 1953.[5] SubGenius members constructed an elaborate account of Dobbs's life, which commentators describe as fictional.[8] They assert that he telepathically contacted Drummond in 1972, before meeting him in person the next year, and that Drummond persuaded Stang to join shortly afterward.[9] Stang has called himself Dobbs's "sacred scribe" and a "professional maven of weirdness".[10][11]

Beliefs

Deities

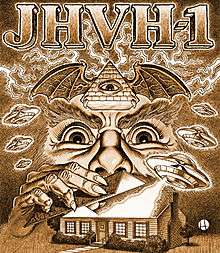

The Church of the SubGenius's ostensible beliefs defy categorization or a simple narrative, often striking outsiders as bizarre and convoluted.[10] The group has an intricate mythology involving gods, aliens, and mutants, which observers usually consider satire of other religions.[5] Its primary deity, generally known as Jehovah 1,[2] is an extraterrestrial who contacted Dobbs in the 1950s. Various accounts state that the encounter occurred while Dobbs was building a television or watching late-night television.[12][13] Jehovah 1 gave him supernatural knowledge of the past and future, in addition to incredible power.[12] Dobbs then posed deep questions to the alien, receiving mysterious answers.[14] Some of their discussion centered on a powerful conspiracy, to which the Church attributes command of the world.[2]

Jehovah 1 and his spouse Eris, regarded by the Church as "relatively evil", are classified as "rebel gods".[15] SubGenius leaders note that Jehovah 1 is wrathful, a quality expressed by his "stark fist of removal".[9] The Church teaches that they are part of the Elder Gods, who are committed to human pain, but that Jehovah 1 is "relatively good" in comparison. Yog-Sothoth, a character from H. P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos, is the Elder Gods' leader. In her 2010 study of the Church of the SubGenius, religious scholar Carole Cusack of the University of Sydney states that Lovecraft's work is a "model for the Church of the SubGenius's approach to scripture", in that aspects of his fiction were treated as real by some within paganism, just as the Church appropriates aspects of popular culture in its spirituality.[16]

J. R. "Bob" Dobbs

SubGenius leaders teach that Dobbs's nature is ineffable and consequently stylize his name with quotation marks.[17][18] They call him a "World Avatar"[9] and hold that he has died and been reborn many times.[10] The Church's primary symbol is an icon of his face in which he smokes a pipe.[2] Stang has said the image was taken from Yellow Pages clip art,[17] and it has been likened to Ward Cleaver,[10] Mark Trail,[13] or a 1950s-era salesman.[2] The Church's canon contains references to aspects of United States culture in that decade;[19] religious scholar Danielle Kirby of RMIT University argues that this type of reference "simultaneously critiques and subverts" the American dream.[20]

In the Church's mythology, Jehovah 1 intended Dobbs to lead a powerful conspiracy and brainwash individuals to make them work for a living. Dobbs refused; instead, he infiltrated the group and organized a counter-movement. Church leaders teach that he was a very intelligent child and, as he grew older, studied several religious traditions, including Sufism, Rosicrucianism, and the Fourth Way.[21] Another key event in his life occurred when he traveled to Tibet, where he learned vital truths about topics including Yetis; the Church teaches that SubGenius members are descended from them. The only relative of Dobbs the Church identifies is his mother, Jane McBride Dobbs—Church leaders cite his lack of resemblance to his mother's husband as the reason for not revealing his father.[21] Dobbs is married to a woman named Connie; SubGenius leaders identify the couple as archetypes of the genders in a belief that resembles Hindu doctrines about Shiva and Parvati.[12] Church literature has variously described Dobbs's occupation as "drilling equipment" or fluoride sales,[9][13] and accounts of his life generally emphasize his good fortune rather than intelligence.[19] SubGenius leaders believe he is capable of time travel, and that this results in occasional changes to doctrine (the "Sacred Doctrine of Erasability"). Consequently, members attempt to follow Dobbs by eschewing unchangeable plans.[19]

Conspiracy and "Slack"

The Church of the SubGenius's literature incorporates many aspects of conspiracy theories,[22] teaching that there is a grand conspiracy at the root of all lesser ones.[17] It says that there are many UFOs, most of which are used by the conspiracy leaders to monitor humans, though a few contain extraterrestrials. In the Church's view, this conspiracy uses a façade of empowering messages but manipulates people so that they become indoctrinated into its service.[9] The Church calls these individuals "pinks" and states that they are blissfully unaware of the organization's power and control.[23] SubGenius leaders teach that most cultural and religious mores are the conspiracy's propaganda.[19] They maintain that their followers, but not the pinks, are capable of developing an imagination; the Church teaches that Dobbs has empowered its members to see through these illusions. Owing to their descent from Yetis, the Church's followers have a capacity for deep understanding that the pinks lack.[9] Cultural studies scholar Solomon Davidoff states that the Church develops a "satiric commentary" on religion, morality, and conspiracies.[22]

SubGenius members believe that those in the service of the conspiracy seek to bar them from "Slack",[22] a quality promoted by the Church. Its teachings center on "Slack"[5] (always capitalized),[18] which is never concisely defined, though Dobbs is said to embody it.[2][24] Church members seek to acquire Slack and believe it will allow them the free, comfortable life (without hard work or responsibility) they claim as an entitlement.[12][25] Sex and the avoidance of work are taught as two key ways to gain Slack.[18] Davidoff believes that Slack is "the ability to effortlessly achieve your goals".[22] Cusack states that the Church's description of Slack as ineffable recalls the way that Tao is described,[9] and Kirby calls Slack a "unique magical system".[26]

Members

The Church of the SubGenius's founders were based in Dallas when they distributed their first document. The SubGenius Foundation moved to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1999.[5] In 2009, Stang claimed the Church had 40,000 members, but the actual number may have been much lower.[27] As of 2012, becoming a minister in the Church consists of paying a $35 fee;[28] Stang has estimated that there are 10,000 ministers[13][29][30] and that the Church's annual income has reached $100,000.[7] In October 2017, The Church moved to Glen Rose, Texas.

Most SubGenius members are male,[14] and, according to Stang, many are social outcasts.[11] He maintains that those who do not fit into society will ultimately triumph over those who do.[7] The Church has experienced success "converting" college students,[10] particularly at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[31] It has also gained popularity in several American cities, including San Francisco, Little Rock, and Cleveland.[11][32] A few Church members have voiced concerns and/or amusement about new members who took the Church too seriously, fearing that they acted like serious cult followers, the very concept the SubGenius parodies.[13] Stang has expressed concern that the Church's doctrines could exacerbate preexisting psychoses of mentally ill devotees, although he believes that the Church genuinely helps many adherents.[11]

Notable associates of the Church include Mark Mothersbaugh,[18] Mojo Nixon,[18] Paul Mavrides,[11] Paul Reubens,[33] members of Negativland,[18] David Byrne, and R. Crumb.[34] Crumb provided early publicity for the church by reprinting Sub Genius Pamphlet #1 in his comics anthology Weirdo.[7] References to the Church are present in several works of art,[35] including the Internet-based collaborative fiction Ong's Hat, the comic book The Middleman, the band Sublime's album 40oz. to Freedom, and the television program Pee-wee's Playhouse.[36][37][38]

Instructions

Church leaders have issued specific instructions to their followers;[39] Robert Latham of the University of California, Riverside, calls their ideology "anarcholibertarian".[40] Five specific commands particularly embody the group's values:

- Shun regular employment and stop working. This encapsulates the Church's view that to repent is to "SLACK OFF",[39] as opposed to working for a living.[20] SubGenius leaders say it is permissible for members to collect public assistance in lieu of maintaining employment.[39]

- Purchase products sold by the Church, which its leaders say Dobbs founded to gain wealth.[41] Unlike most religious groups, the Church proudly admits it is for-profit (presumably mocking religious groups that seem to have ulterior financial motives).[18] Cusack sees the instruction to buy as an ironic parody of the "greed is good" mentality of the 1980s,[39] and Kirby notes that although the group emphasizes "the consumption of popular cultural artefacts", this consumption is "simultaneously de-emphasized by the processes of remix".[42]

- Rebel against "law and order". Specifically, the Church condemns security cameras and encourages computer hacking. Cusack notes that this instruction recalls Robert Anton Wilson's critique of law and order.

- Rid the world of everyone who did not descend from Yetis.[39] SubGenius leaders teach that Dobbs hopes to rid the Earth of 90% of humanity, making the Earth "clear".[41] The group praises drug abuse and abortion as effective methods of culling unneeded individuals.

- Exploit fear, specifically that of people who are part of the conspiracy. Church leaders teach conspiracy members fear SubGenius devotees.[39]

Events

Devivals

Local groups of members of the Church of the SubGenius are known as "clenches". They host periodic events known as "devivals", which include sermons, music, and other art forms.[5] The term is used by both the Church of the Subgenius and Discordianism for a gathering or festival of followers. The name is a pun on Christian revivals.[43]

At devivals, leaders take comical names and give angry rants.[23] Many take place at bars or similar venues.[27] Cusack compares the style of the services to Pentecostal revivalism;[23] David Giffels of the Akron Beacon Journal calls them "campy preaching sessions".[11] Cusack posits that these events are examples of Peter Lamborn Wilson's concept of Temporary Autonomous Zones, spaces in which the ordinary constraints of social control are suspended.[44] On one occasion, the presence of a Church leader's wife at a SubGenius meeting that included public nudity and a goat costume contributed to her losing custody of her children in a court case. But the publicity surrounding the event was a boon to the Church's recruitment efforts.[45]

The Church also celebrates several holidays in honor of characters from fiction and popular culture, such as Monty Python, Dracula, and Klaatu.[46] The Association for Consciousness Exploration and pagan groups have occasionally assisted the Church in its events.[18][27] Some SubGenius members put little emphasis on meetings, citing the Church's focus on individualism, though the Book of the SubGenius discusses community.[47]

SubGenius devivals are not regularly scheduled, but are recorded on the SubGenius website.[48] Devivals have been held in multiple U.S. states, as well as China, the Netherlands, and Germany. The Church has also held Devivals at non-SubGenius events, such as Burning Man and the Starwood Festival.[49]

The Cyclone of Slack[50][51] was a devival in Portland, Oregon, in October 2009 put on by the Church of the Subgenius[52] and the organizers of Esozone. One of its more bizarre moments was when the alcohol and fire-and-brimstone sermon-fueled crowd in front of the stage began to sit down in twos and threes when the Duke of Uke began to play his ukulele.[53]

The "Go Fuck Yourself" devival was held in Astoria, New York, in October 2010 by the Church of the Subgenius at the Wonderland Collective.[54]

X-Day

In early SubGenius literature, July 5, 1998, was introduced as a significant date, later becoming known as "X-Day".[39] The Church held that Dobbs identified the date's significance in the 1950s,[30] claiming that the world was to experience a massive change on that date when Xists, beings from Planet X, would arrive on Earth.[29] SubGenius leaders said their paying members would be transported onto spaceships for union with goddesses as the world was destroyed,[55] though a few posited that they would be sent to a joyful hell.[11] In anticipation of the event, X-Day "drills" were held in 1996 and 1997.[56]

In July 1998, the Church held a large devival at a "clothing-optional" campground in Sherman, New York,[29][31] attended by about 400 members.[30] The event was ostensibly to celebrate the coming of aliens. When their appearance was not detected using the technology available at the time, Stang speculated that they might arrive in 8661, an inversion of 1998;[29] this has been interpreted as a satire of the way that religious groups have revised prophecies after their failures.[55] Some critics have dismissed the event as a prank or "performance art".[29] Another theory is that The Conspiracy has lied about what year the present year actually is (just as they have lied about everything else), so that the liberation date would seem to pass without fulfillment and cause followers to lose faith. As a precaution, SubGenius members continue to gather for X-Day every July 5. At these events, the non-appearance of the aliens is celebrated.[26][57] Cusack calls the productions carnivalesque[57] or an echo of ancient Greek satyr plays.[29]

Publishing

Online

The Church of the SubGenius established a website in May 1993,[58] and its members were very active on Usenet in the 1990s.[10]

Print

Although it has gained a significant online presence, it was successful before the advent of Internet communities.[59] The Church was a pioneer in the religious use of zines;[60] Cusack notes that its use of the medium can be seen as a rejection of the alienation of labor practices.[61]

The SubGenius Foundation has published several official teachings, as well as non-doctrinal works by Stang.[5] The Book of the SubGenius, which discusses Slack at length, was published by Simon & Schuster and sold 30,000 copies in its first five years in print.[32][62] Kirby calls it a "call to arms for the forces of absurdity".[26] Its juxtaposition, visual style, and content mirror the group as a whole.[63] It draws themes from fiction as well as established and new religions, parodying a number of topics, including the Church of the SubGenius itself.[26]

A number of SubGenius members have written stories to build their mythology, which have been compiled and published.[61] Their core texts are disordered, presented in the style of a collage.[64] Kirby notes that the group's texts are a bricolage of cultural artifacts remixed into a new creation.[20][63] In this process, Kirby argues, they interweave and juxtapose a variety of concepts, which she calls a "web of references".[20]

Radio

The Church of the SubGenius hosts several radio shows throughout the world, including broadcasters in Atlanta, Ohio, Maryland, and California. Several radio stations in the United States and two in Canada broadcast The Hour of Slack, the Church’s most popular audio production.[65]

Podcast

The Hour of Slack can also be heard in podcast form.[66][67]

Analysis and commentary

Comparative religion

The Church's teachings are often perceived as satirizing Christianity and Scientology,[2] earning them a reputation as a parody religion.[5] Church leaders have said that Dobbs met L. Ron Hubbard, and SubGenius narratives echo extraterrestrial themes found in Scientology.[68] Cusack notes Jehovah 1 bears noticeable similarities to Xenu, a powerful alien found in some Scientologist writings.[41] The Church's rhetoric has also been seen as a satirical imitation of the televangelism of the 1980s.[34] Cusack sees the Church's faux commercialism as culture jamming targeting prosperity theology,[46] calling it "a strikingly original innovation in contemporary religion".[35] Religious scholar Thomas Alberts of the University of London views the Church as attempting to "subvert the idea of authenticity in religion" by mirroring other religions to create a sense of both similarity and alterity.[69]

Cusack compares the Church of the SubGenius to the Ranters, a radical 17th-century pantheist movement in England that made statements that shocked many hearers, attacking traditional notions of religious orthodoxy and political authority. In her view, this demonstrates that the Church of the SubGenius has "legitimate pedigree in the history of Western religion".[70] The American journalist Michael Muhammad Knight likens the Church to the Moorish Orthodox Church of America, a 20th-century American syncretic religious movement, citing their shared emphasis on freedom.[38]

There are a number of similarities between the Church of the SubGenius and Discordianism. Eris, the goddess of chaos worshiped by adherents of the latter, is believed by members of the Church of the SubGenius to be Jehovah 1's wife and an ally to humans. Like Discordianism, the Church of the SubGenius rejects absolute truth and embraces contradictions and paradoxes.[19] Religious scholar David Chidester of the University of Cape Town views the Church as a "Discordian offshoot",[71] and Kirby sees it as "a child of the Discordians".[64] Both groups were heavily influenced by the writings of Robert Anton Wilson, whom SubGenius members call "Pope Bob".[19][72] Kirby states that the two groups have elements of bricolage and absurdity in common, but the Church of the SubGenius more explicitly remixes pop culture.[26]

Categorization

Scholars often have difficulty defining the Church.[73] Most commentators have placed the Church in the category of "joke religions", which is usually seen as pejorative. Kirby sees this categorization as partially accurate because irony is an essential aspect of the faith.[3] Other terms used to describe the Church include "faux cult",[34] "[postmodern] cult",[10] "satirical pseudoreligion",[62] "sophisticated joke religion",[73] "anti-religion religion",[30] and "high parody of cultdom".[13] Members of the Church, however, have consistently maintained that they practice a religion.[57] Stang has described the group as both "satire and a real stupid religion", and contends that it is more honest about its nature than are other religions.[45]

Cusack states that the Church "must be accorded the status of a functional equivalent of religion, at the very least, if not 'authentic' religion".[2] She sees it as "arguably a legitimate path to liberation", citing its culture jamming and activism against commercialism.[2] Kirby posits that the Church is a religion masquerading as a joke, rather than the reverse: in her view, it is a spiritual manifestation of a cultural shift toward irony.[3] Alberts believes there is broad agreement that the Church is fundamentally a different type of group than religions that date to antiquity; he prefers to use the term "fake religion" to describe it. He sees it, along with Discordianism, as part of a group of "popular movements that look and feel like religion, but whose apparent excess, irreverence and arbitrariness seem to mock religion".[74] Knight characterizes the Church as "at once a postmodern spoof of religion and a viable system in its own right".[38]

Appraisal

Kirby argues that the Church forms a counterpart to Jean Baudrillard's concept of hyperreality, arguing, "they create, rather than consume, popular culture in the practice of their spirituality".[75] She calls their remixing of popular culture sources an "explicitly creative process",[20] maintaining that it prompts the reader to adopt some of the group's views by forcing "the individual to reconsider normative methods of approaching the content".[20] She states that the group attempts to "strip references of their original meaning without necessarily losing their status as icons".[20]

Kirby also sees the Church's goal as deconstructing "normative modes of thought and behavior" in American culture;[59] she believes that it attempts to fight culturally ingrained thought patterns by shocking people.[26] She argues that traditional approaches to religion cast seriousness as a measure of devotion, an approach she believes has failed in contemporary society. She feels that irony is a common value that most religions have ignored. By embracing the quality, she maintains, the Church of the SubGenius offers a more accessible worldview than many groups.[3]

Literature scholar Paul Mann of Pomona College is critical of the Church of the SubGenius. He notes that the Church purports to present the truth through absurdity and faults it for insufficiently examining the concept of truth itself.[76] In addition, he believes that the group undermines its attempts to take a radical perspective with its "hysterical, literal, fantastic embrace" of criticism.[77]

Anarchist writer Bob Black, a former member, has criticized the Church, alleging that it has become conformist and submissive to authority. He believes that although it initially served to satirize cults, it later took on some of their aspects. In 1992, allegations of cultlike behavior also appeared in the newspaper Bedfordshire on Sunday after a spate of SubGenius-themed vandalism struck the English town of Bedford.[18]

Publications

Books

- SubGenius Foundation (1987). Book of the SubGenius. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-63810-8.

- Ivan Stang (1988). High Weirdness by Mail. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-64260-0.

- Ivan Stang (1990). Three-fisted tales of "Bob": Short Stories in the SubGenius Mythos. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-67190-7.

- Ivan Stang; SubGenius Foundation (1994). Revelation X: the "Bob" Apocryphon: Appointed to be Read in Churches. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-77006-8.

- Ivan Stang (2006). The SubGenius Psychlopaedia of Slack: The Bobliographon. Running Press. ISBN 978-1-56025-939-8.

- Dave DeLuca (2017). Neighborworld. SubGenius Foundation. ASIN B075W2QD9V.

Videos

- Stang, Ivan; Holland, Cordt; Robins, Hal (2006) [1991]. Arise!: the SubGenius Video (DVD-R). SubGenius Moving Pictures. OCLC 388112825.

See also

Notes

- Solomon, Dan (2 November 2017). "The Church of the SubGenius Finally Plays It Straight". Texas Monthly. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

Dan Solomon: The SubGenius has been a put-on for so long. What's it like to drop that mask and tell the story in a real way now? Ivan Stang: It's fun for me. I've been keeping a straight face for thirty-five years. Your face gets tired. I really would not drop character for a long, long time.

- Cusack 2010, p. 84.

- Kirby 2012, p. 43.

- Chryssides 2012, p. 95.

- Cusack 2010, p. 83.

- Shea 2006.

- Niesel 2000.

- Kinsella 2011, p. 67.

- Cusack 2010, p. 86.

- Batz 1995.

- Giffels 1995.

- Cusack 2010, p. 85.

- Rea 1985.

- Cusack 2010, p. 102.

- Cusack 2010, pp. 86 & 101.

- Cusack 2010, p. 101.

- Hart 1992.

- Leiby 1994.

- Cusack 2010, p. 88.

- Kirby 2012, p. 50.

- Cusack 2010, pp. 84–6.

- Davidoff 2003, p. 170.

- Cusack 2010, p. 93.

- Duncombe 2005, p. 222.

- Duncombe 2005, p. 226.

- Kirby 2012, p. 49.

- Cusack 2010, p. 106.

- SubGenius.com Sales.

- Cusack 2010, p. 90.

- Scoblionkov 1998.

- Yuen 1998.

- Ashbrook 1988.

- Cusack 2010, p. 94.

- Callahan 1996.

- Cusack 2010, p. 111.

- Kinsella 2011, p. 64–7.

- Lloyd 2008.

- Knight 2012, p. 96.

- Cusack 2010, p. 89.

- Latham 2002, p. 94.

- Cusack 2010, p. 87.

- Kirby 2012, p. 52.

- Cusack, Carole M. (2010), "The Church of the SubGenius: Science Fiction Mythos, Culture Jamming and the Sacredness of Slack", Invented Religions: Imagination, Fiction and Faith, Ashgate Publishing, p. 95, ISBN 978-0-7546-6780-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cusack 2010, p. 97.

- Cusack 2010, p. 107.

- Cusack 2010, p. 104.

- Cusack 2010, pp. 98–9.

- "Reports on Great Devivals of yore".

- "SubSite - Past Events". www.subgenius.com. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- "Salvation - $10". 2009-10-22. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- "Cyclone of Slack". Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- "Hour of Slack #1232 - Portland Cyclone of Slack Devival 1 - 59:08". Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- "Duke of Uke calms the Devival with the healing power of the ukulele". Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- "SUBGENIUS DEVIVAL IN ASTORIA".

- Gunn & Beard 2000, p. 269.

- SubGenius.com Devivals.

- Cusack 2010, p. 98.

- Ciolek 2003, p. 800.

- Kirby 2012, p. 44.

- Kinsella 2011, p. 64.

- Cusack 2010, p. 100.

- Stein 1993, p. 179.

- Kirby 2012, p. 51.

- Kirby 2012, p. 48.

- "SubSite - Radio". www.subgenius.com. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- "SubSite - Radio". www.subgenius.com. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- "hourofslack.libsyn.com". Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- Cusack 2010, p. 105.

- Alberts 2008, p. 127.

- Cusack 2010, pp. 106–7.

- Chidester 2005, p. 198.

- The Daily Telegraph, "Robert Anton Wilson".

- Cusack 2010, p. 109.

- Alberts 2008, p. 126.

- Kirby 2012, pp. 42–3.

- Mann 1999, p. 156.

- Mann 1999, p. 158.

References

Books

- Chidester, David (2005), Authentic Fakes: Religion and American Popular Culture, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24280-7CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chryssides, George (2012), Historical Dictionary of New Religious Movements, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-81086-194-7

- Ciolek, T. Matthew (2003), "Online Religion", in Hossein Bidgoli (ed.), The Internet Encyclopedia, 2, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-22204-0

- Cusack, Carole M. (2010), "The Church of the SubGenius: Science Fiction Mythos, Culture Jamming and the Sacredness of Slack", Invented Religions: Imagination, Fiction and Faith, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-6780-3CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidoff, Solomon (2003), Peter Knight (ed.), Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-812-9

- Duncombe, Stephen (2005), "Sabotage, Slack and the Zinester Search for Non-Alienated Labour", in Bell, David; Hollows, Joanne (eds.), Ordinary Lifestyles, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-335-22420-3

- Kinsella, Michael (2011), Legend-Tripping Online: Supernatural Folklore and the Search for Ong's Hat, University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 978-1-60473-983-1CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kirby, Danielle (2012), "Occultural Bricolage and Popular Culture: Remix and Art in Discordianism, the Church of the SubGenius, the Temple of Psychick Youth", in Adam Possamai (ed.), Handbook of Hyper-real Religions, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-21881-9

- Knight, Michael Muhammad (2012), William S. Burroughs vs. The Qur'an, Soft Skull Press, ISBN 978-1-59376-415-9

- Latham, Robert (2002), Consuming Youth: Vampires, Cyborgs, and the Culture of Consumption, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-46891-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mann, Paul (1999), "Stupid Undergrounds", Masocriticism, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-4032-2

Journals

- Alberts, Thomas (2008), "Virtually Real: Fake Religions and Problems of Authenticity in Religion", Culture and Religion, 9 (5): 125–39, doi:10.1080/14755610802211510

- Gunn, Joshua; Beard, David (2000), "On the Apocalyptic Sublime", Southern Communication Journal, 65 (4): 269–86, doi:10.1080/10417940009373176CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stein, Jean (1993), "Slacking toward Bethlehem", Grand Street (44): 176–88, JSTOR 25007625

Magazines

- Callahan, Maureen (March 4, 1996), "Slacking Off", New York, retrieved August 19, 2012

- Scoblionkov, Deborah (July 6, 1998), "Armageddon Ends Badly", Wired, retrieved August 28, 2012

- Shea, Mike (November 2006), "Douglass St. Clair Smith", Texas Monthly, retrieved August 5, 2013

Newspapers

- "Robert Anton Wilson", The Daily Telegraph, January 13, 2007, retrieved October 27, 2012

- Ashbrook, Tom (July 17, 1988), "'Saving' Souls Irreverently", The Boston Globe, archived from the original on May 17, 2013, retrieved August 19, 2012 (subscription required)

- Batz, Bob (February 17, 1995), "In 'Bob' they Trust", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, retrieved August 19, 2012 (subscription required)

- Giffels, David (August 2, 1995), "Eschew Normalcy Rev. Stang and his Church of SubGenius Prefer Satire to Sacredness", Akron Beacon Journal, retrieved August 19, 2012 (subscription required)

- Hart, Hugh (September 16, 1992), "Behind Every SubGenius Conspiracy Is An Ordinary Bob", The Chicago Tribune, retrieved August 20, 2012

- Leiby, Richard (February 8, 1995), "Holy Smoke, It's Bob!", The Washington Post, retrieved August 19, 2012 (subscription required)

- Lloyd, Robert (June 16, 2008), "Comic-Book Antics", Los Angeles Times, retrieved August 20, 2012 (subscription required)

- Niesel, Jeff (April 6, 2000), "Slack Is Back", Cleveland Scene, retrieved October 28, 2012

- Rea, Steven (May 4, 1985), "The 'Weirdest Supercult' Prepares to Gather the Flock to the Church of the SubGenius", The Philadelphia Inquirer, retrieved August 19, 2012 (subscription required)

- Yuen, Laura (July 5, 1998), "Apocalypse, nah", The Boston Globe, archived from the original on May 17, 2013, retrieved August 28, 2012 (subscription required)

Websites

- "Reports on Great Devivals of Yore", SubGenius.com, Hall of Mindless Fun, Church of the SubGenius, retrieved October 27, 2012

- "Salvation/Membership/Ordainment", SubGenius.com, Official Outreach Sales, Church of the SubGenius, retrieved October 27, 2012

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Church of the SubGenius. |

- Official website

- Burning ‘Bob’: Cacophony, Burning Man, and the Church of the SubGenius 2013 interview with Church founders Drummond and Stang, archived from the original May 22, 2014.

- Carleton, Lee (2014), Doctoral Dissertation "Rhetorical Ripples: The Church of the SubGenius, Kenneth Burke & Comic, Symbolic Tinkering"