Subduction

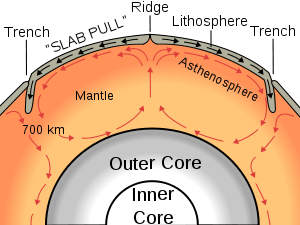

Subduction is a geological process that takes place at convergent boundaries of tectonic plates where one plate moves under another and is forced to sink due to high gravitational potential energy into the mantle.[1] Regions where this process occurs are known as subduction zones. Rates of subduction are typically measured in centimeters per year, with the average rate of convergence being approximately two to eight centimeters per year along most plate boundaries.[2]

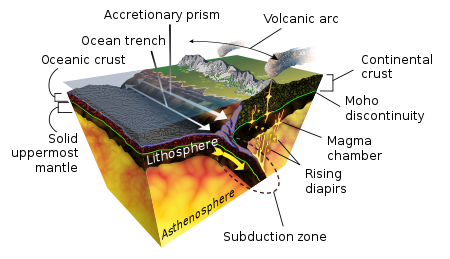

Plates include both oceanic crust and continental crust. Stable subduction zones involve the oceanic lithosphere of one plate sliding beneath the continental or oceanic lithosphere of another plate due to the higher density of the oceanic lithosphere. This means that the subducted lithosphere is always oceanic while the overriding lithosphere may or may not be oceanic. Subduction zones are sites that usually have a high rate of volcanism and earthquakes. Furthermore, subduction zones develop belts of deformation and metamorphism in the subducting crust, whose exhumation is part of orogeny and also leads to mountain building in addition to collisional thickening.

General description

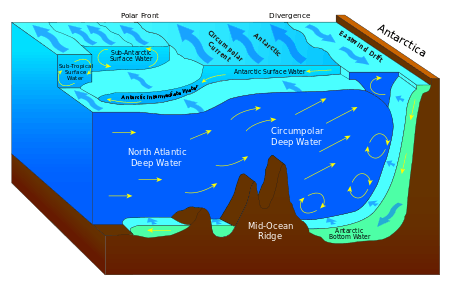

Subduction zones are sites of gravitational sinking of Earth's lithosphere (the crust plus the top non-convecting portion of the upper mantle).[3] Subduction zones exist at convergent plate boundaries where one plate of oceanic lithosphere converges with another plate. The descending slab, the subducting plate, is over-ridden by the leading edge of the other plate. The slab sinks at an angle of approximately twenty-five to forty-five degrees to Earth's surface. This sinking is driven by the temperature difference between the subducting oceanic lithosphere and the surrounding mantle asthenosphere, as the colder oceanic lithosphere has, on average, a greater density. At a depth of greater than 60 kilometers, the basalt of the oceanic crust is converted to a metamorphic rock called eclogite. At that point, the density of the oceanic crust increases and provides additional negative buoyancy (downwards force). It is at subduction zones that Earth's lithosphere, oceanic crust and continental crust, sedimentary layers and some trapped water are recycled into the deep mantle.

Earth is so far the only planet where subduction is known to occur. Subduction is the driving force behind plate tectonics, and without it, plate tectonics could not occur.

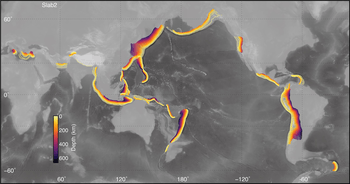

Oceanic subduction zones dive down into the mantle beneath 55,000 km (34,000 mi) of convergent plate margins (Lallemand, 1999), almost equal to the cumulative 60,000 km (37,000 mi) of mid-ocean ridges. Subduction zones burrow deeply but are imperfectly camouflaged, and geophysics and geochemistry can be used to study them. Not surprisingly, the shallowest portions of subduction zones are known best. Subduction zones are strongly asymmetric for the first several hundred kilometers of their descent. They start to go down at oceanic trenches. Their descents are marked by inclined zones of earthquakes that dip away from the trench beneath the volcanoes and extend down to the 660-kilometer discontinuity. Subduction zones are defined by the inclined array of earthquakes known as the Wadati–Benioff zone after the two scientists who first identified this distinctive aspect. Subduction zone earthquakes occur at greater depths (up to 600 km (370 mi)) than elsewhere on Earth (typically less than 20 km (12 mi) depth); such deep earthquakes may be driven by deep phase transformations, thermal runaway, or dehydration embrittlement.[4][5]

The subducting basalt and sediment are normally rich in hydrous minerals and clays. Additionally, large quantities of water are introduced into cracks and fractures created as the subducting slab bends downward.[6] During the transition from basalt to eclogite, these hydrous materials break down, producing copious quantities of water, which at such great pressure and temperature exists as a supercritical fluid. The supercritical water, which is hot and more buoyant than the surrounding rock, rises into the overlying mantle where it lowers the pressure in (and thus the melting temperature of) the mantle rock to the point of actual melting, generating magma. The magmas, in turn, rise (and become labeled diapirs) because they are less dense than the rocks of the mantle. The mantle-derived magmas (which are basaltic in composition) can continue to rise, ultimately to Earth's surface, resulting in a volcanic eruption. The chemical composition of the erupting lava depends upon the degree to which the mantle-derived basalt interacts with (melts) Earth's crust and/or undergoes fractional crystallization.

Above subduction zones, volcanoes exist in long chains called volcanic arcs. Volcanoes that exist along arcs tend to produce dangerous eruptions because they are rich in water (from the slab and sediments) and tend to be extremely explosive. Krakatoa, Nevado del Ruiz, and Mount Vesuvius are all examples of arc volcanoes. Arcs are also known to be associated with precious metals such as gold, silver and copper believed to be carried by water and concentrated in and around their host volcanoes in rock called "ore".

History

Harry Hammond Hess, who during World War II serving as part of the United States Navy Reserve became fascinated in the ocean floor, studied the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and proposed that hot molten rock was added to the crust at the ridge and expanded the seafloor outward. This theory was to become known as seafloor spreading. However, considering that throughout the geological history of the Earth there was never a change in its circumference, Hess supposed that somehow older seafloor had to be consumed somewhere else, and theorized this hypothetical process would take place at oceanic trenches, where the crust would be melted and recycled in the Earth's mantle.

In 1964, George Plafker conducted research on the Good Friday earthquake in Alaska. He concluded that the cause of the earthquake was a megathrust reaction in the Aleutian Trench, a result of the Alaskan continental crust overlapping the Pacific oceanic crust. This meant that the Pacific crust was being forced downward, or subducted, beneath the Alaskan crust. The concept of subduction would play a role in the development of the plate tectonics theory.

Theory on origin

Initiation

Although the process of subduction as it occurs today is fairly well understood, its origin remains a matter of discussion and continuing study. Subduction initiation can occur spontaneously if denser oceanic lithosphere is able to founder and sink beneath adjacent oceanic or continental lithosphere; alternatively, existing plate motions can induce new subduction zones by forcing oceanic lithosphere to rupture and sink into the asthenosphere.[7] Both models can eventually yield self-sustaining subduction zones, as oceanic crust is metamorphosed at great depth and becomes denser than the surrounding mantle rocks. Results from numerical models generally favor induced subduction initiation for most modern subduction zones,[8][9] which is supported by geologic studies,[10][11] but other analogue modeling shows the possibility of spontaneous subduction from inherent density differences between two plates at passive margins,[12][13] and observations from the Izu-Bonin-Mariana subduction system are compatible with spontaneous subduction nucleation.[14][15] Furthermore, subduction is likely to have spontaneously initiated at some point in Earth's history, as induced subduction nucleation requires existing plate motions, though an unorthodox proposal by A. Yin suggests that meteorite impacts may have contributed to subduction initiation on early Earth.[16]

Geophysicist Don L. Anderson has hypothesized that plate tectonics could not happen without the calcium carbonate laid down by bioforms at the edges of subduction zones. The massive weight of these sediments could be softening the underlying rocks, making them pliable enough to plunge.[17]

Modern-style subduction

Modern-style subduction is characterized by low geothermal gradients and the associated formation of high-pressure low temperature rocks such as eclogite and blueschist.[18][19] Likewise, rock assemblages called ophiolites, associated to modern-style subduction, also indicate such conditions.[18] Eclogite xenoliths found in the North China Craton provide evidence that modern-style subduction occurred at least as early as 1.8 Ga ago in the Paleoproterozoic Era.[18] Nevertheless, the eclogite itself was produced by oceanic subduction during the assembly of supercontinents at about 1.9–2.0 Ga.

Blueschist is a rock typical for present-day subduction settings. Absence of blueschist older than Neoproterozoic reflect more magnesium-rich compositions of Earth's oceanic crust during that period.[20] These more magnesium-rich rocks metamorphose into greenschist at conditions when modern oceanic crust rocks metamorphose into blueschist.[20] The ancient magnesium-rich rocks means that Earth's mantle was once hotter, but not that subduction conditions were hotter. Previously, lack of pre-Neoproterozoic blueschist was thought to indicate a different type of subduction.[20] Both lines of evidence refute previous conceptions of modern-style subduction having been initiated in the Neoproterozoic Era 1.0 Ga ago.[18][20]

Effects

Metamorphism

Volcanic activity

Volcanoes that occur above subduction zones, such as Mount St. Helens, Mount Etna and Mount Fuji, lie at approximately one hundred kilometers from the trench in arcuate chains, hence the term volcanic arc. Two kinds of arcs are generally observed on Earth: island arcs that form on oceanic lithosphere (for example, the Mariana and the Tonga island arcs), and continental arcs such as the Cascade Volcanic Arc, that form along the coast of continents. Island arcs are produced by the subduction of oceanic lithosphere beneath another oceanic lithosphere (ocean-ocean subduction) while continental arcs formed during subduction of oceanic lithosphere beneath a continental lithosphere (ocean-continent subduction). An example of a volcanic arc having both island and continental arc sections is found behind the Aleutian Trench subduction zone in Alaska.

The arc magmatism occurs one hundred to two hundred kilometers from the trench and approximately one hundred kilometers above the subducting slab. This depth of arc magma generation is the consequence of the interaction between hydrous fluids, released from the subducting slab, and the arc mantle wedge that is hot enough to melt with the addition of water. It has also been suggested that the mixing of fluids from a subducted tectonic plate and melted sediment is already occurring at the top of the slab before any mixing with the mantle takes place.[21]

Arcs produce about 25% of the total volume of magma produced each year on Earth (approximately thirty to thirty-five cubic kilometers), much less than the volume produced at mid-ocean ridges, and they contribute to the formation of new continental crust. Arc volcanism has the greatest impact on humans because many arc volcanoes lie above sea level and erupt violently. Aerosols injected into the stratosphere during violent eruptions can cause rapid cooling of Earth's climate and affect air travel.

Earthquakes and tsunamis

The strains caused by plate convergence in subduction zones cause at least three types of earthquakes. Earthquakes mainly propagate in the cold subducting slab and define the Wadati–Benioff zone. Seismicity shows that the slab can be tracked down to the upper mantle/lower mantle boundary (approximately six hundred kilometer depth).

Nine of the ten largest earthquakes of the last 100 years were subduction zone events, which included the 1960 Great Chilean earthquake, which, at M 9.5, was the largest earthquake ever recorded; the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami; and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. The subduction of cold oceanic crust into the mantle depresses the local geothermal gradient and causes a larger portion of Earth to deform in a more brittle fashion than it would in a normal geothermal gradient setting. Because earthquakes can occur only when a rock is deforming in a brittle fashion, subduction zones can cause large earthquakes. If such a quake causes rapid deformation of the sea floor, there is potential for tsunamis, such as the earthquake caused by subduction of the Indo-Australian Plate under the Euro-Asian Plate on December 26, 2004 that devastated the areas around the Indian Ocean. Small tremors which cause small, nondamaging tsunamis, also occur frequently.

A study published in 2016 suggested a new parameter to determine a subduction zone's ability to generate mega-earthquakes.[22] By examining subduction zone geometry and comparing the degree of curvature of the subducting plates in great historical earthquakes such as the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman and the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, it was determined that the magnitude of earthquakes in subduction zones is inversely proportional to the degree of the fault's curvature, meaning that "the flatter the contact between the two plates, the more likely it is that mega-earthquakes will occur."[23]

Outer rise earthquakes occur when normal faults oceanward of the subduction zone are activated by flexure of the plate as it bends into the subduction zone.[24] The 2009 Samoa earthquake is an example of this type of event. Displacement of the sea floor caused by this event generated a six-meter tsunami in nearby Samoa.

Anomalously deep events are a characteristic of subduction zones, which produce the deepest quakes on the planet. Earthquakes are generally restricted to the shallow, brittle parts of the crust, generally at depths of less than twenty kilometers. However, in subduction zones, quakes occur at depths as great as 700 km (430 mi). These quakes define inclined zones of seismicity known as Wadati–Benioff zones which trace the descending lithosphere.

Seismic tomography has helped detect subducted lithosphere, slabs, deep in the mantle where there are no earthquakes. About one hundred slabs have been described in terms of depth and their timing and location of subduction.[25] The great seismic discontinuities in the mantle, at 410 km (250 mi) depth and 670 km (420 mi), are disrupted by the descent of cold slabs in deep subduction zones. Some subducted slabs seem to have difficulty penetrating the major discontinuity that marks the boundary between upper mantle and lower mantle at a depth of about 670 kilometers. Other subducted oceanic plates have sunk all the way to the core-mantle boundary at 2890 km depth. Generally slabs decelerate during their descent into the mantle, from typically several cm/yr (up to ~10 cm/yr in some cases) at the subduction zone and in the uppermost mantle, to ~1 cm/yr in the lower mantle.[25] This leads to either folding or stacking of slabs at those depths, visible as thickened slabs in Seismic tomography. Below ~1700 km, there might be a limited acceleration of slabs due to lower viscosity as a result of inferred mineral phase changes until they approach and finally stall at the core-mantle boundary.[25] Here the slabs are heated up by the ambient heat and are not detected anymore ~300 Myr after subduction.[25]

Orogeny

Orogeny is the process of mountain building. Subducting plates can lead to orogeny by bringing oceanic islands, oceanic plateaus, and sediments to convergent margins. The material often does not subduct with the rest of the plate but instead is accreted (scraped off) to the continent, resulting in exotic terranes. The collision of this oceanic material causes crustal thickening and mountain-building. The accreted material is often referred to as an accretionary wedge, or prism. These accretionary wedges can be identified by ophiolites (uplifted ocean crust consisting of sediments, pillow basalts, sheeted dykes, gabbro, and peridotite).[26]

Subduction may also cause orogeny without bringing in oceanic material that collides with the overriding continent. When the subducting plate subducts at a shallow angle underneath a continent (something called "flat-slab subduction"), the subducting plate may have enough traction on the bottom of the continental plate to cause the upper plate to contract leading to folding, faulting, crustal thickening and mountain building. Flat-slab subduction causes mountain building and volcanism moving into the continent, away from the trench, and has been described in North America (i.e. Laramide orogeny), South America and East Asia.[25]

The processes described above allow subduction to continue while mountain building happens progressively, which is in contrast to continent-continent collision orogeny, which often leads to the termination of subduction.

Subduction angle

Subduction typically occurs at a moderately steep angle right at the point of the convergent plate boundary. However, anomalous shallower angles of subduction are known to exist as well as some that are extremely steep.[27]

- Flat-slab subduction (subducting angle less than 30°) occurs when subducting lithosphere, called a slab, subducts nearly horizontally. The relatively flat slab can extend for hundreds of kilometers. That is abnormal, as the dense slab typically sinks at a much steeper angle directly at the subduction zone. Because subduction of slabs to depth is necessary to drive subduction zone volcanism (through the destabilization and dewatering of minerals and the resultant flux melting of the mantle wedge), flat-slab subduction can be invoked to explain volcanic gaps. Flat-slab subduction is ongoing beneath part of the Andes causing segmentation of the Andean Volcanic Belt into four zones. The flat-slab subduction in northern Peru and the Norte Chico region of Chile is believed to be the result of the subduction of two buoyant aseismic ridges, the Nazca Ridge and the Juan Fernández Ridge, respectively. Around Taitao Peninsula flat-slab subduction is attributed to the subduction of the Chile Rise, a spreading ridge. The Laramide Orogeny in the Rocky Mountains of United States is attributed to flat-slab subduction.[28] Then, a broad volcanic gap appeared at the southwestern margin of North America, and deformation occurred much farther inland; it was during this time that the basement-cored mountain ranges of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, South Dakota, and New Mexico came into being. The most massive subduction zone earthquakes, so-called "megaquakes", have been found to occur in flat-slab subduction zones.[29]

- Steep-angle subduction (subducting angle greater than 70°) occurs in subduction zones where Earth's oceanic crust and lithosphere are old and thick and have, therefore, lost buoyancy. The steepest dipping subduction zone lies in the Mariana Trench, which is also where the oceanic crust, of Jurassic age, is the oldest on Earth exempting ophiolites. Steep-angle subduction is, in contrast to flat-slab subduction, associated with back-arc extension[30] of crust making volcanic arcs and fragments of continental crust wander away from continents over geological times leaving behind a marginal sea.

Importance

Subduction zones are important for several reasons:

- Subduction Zone Physics: Sinking of the oceanic lithosphere (sediments, crust, mantle), by contrast of density between the cold and old lithosphere and the hot asthenospheric mantle wedge, is the strongest force (but not the only one) needed to drive plate motion and is the dominant mode of mantle convection.

- Subduction Zone Chemistry: The subducted sediments and crust dehydrate and release water-rich (aqueous) fluids into the overlying mantle, causing mantle melting and fractionation of elements between surface and deep mantle reservoirs, producing island arcs and continental crust. Hot fluids in subduction zones also alter the mineral compositions of the subducting sediments and potentially the habitability of the sediments for microorganisms.[31]

- Subduction zones drag down subducted oceanic sediments, oceanic crust, and mantle lithosphere that interact with the hot asthenospheric mantle from the over-riding plate to produce calc-alkaline series melts, ore deposits, and continental crust.

- Subduction zones pose significant threats to lives, property, economic vitality, cultural and natural resources, and quality of life. The tremendous magnitudes of earthquakes or volcanic eruptions can also have knock-on effects with global impact.[32]

Subduction zones have also been considered as possible disposal sites for nuclear waste in which the action of subduction itself would carry the material into the planetary mantle, safely away from any possible influence on humanity or the surface environment. However, that method of disposal is currently banned by international agreement.[33][34][35][36] Furthermore, plate subduction zones are associated with very large megathrust earthquakes, making the effects on using any specific site for disposal unpredictable and possibly adverse to the safety of longterm disposal.[34]

See also

- Plate tectonics – The scientific theory that describes the large-scale motions of Earth's lithosphere

- Divergent boundary – Linear feature that exists between two tectonic plates that are moving away from each other

- Back-arc basin – Submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones

- Divergent double subduction – Two parallel subduction zones with different directions are developed on the same oceanic plate

- List of tectonic plate interactions – Definitions and examples of the interactions between the relatively mobile sections of the lithosphere

- Obduction – The overthrusting of oceanic lithosphere onto continental lithosphere at a convergent plate boundary

- Oceanic trench – Long and narrow depressions of the sea floor

- Paired metamorphic belts – Sets of juxtaposed linear rock units that display contrasting metamorphic mineral assemblages

- Slab window – A gap that forms in a subducted oceanic plate when a mid-ocean ridge meets with a subduction zone and the ridge is subducted

References

- Stern, Robert J. (2002), "Subduction zones", Reviews of Geophysics, 40 (4): 1012, Bibcode:2002RvGeo..40.1012S, doi:10.1029/2001RG000108

- Defant, M. J. (1998). Voyage of Discovery: From the Big Bang to the Ice Age. Mancorp. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-931541-61-2.

- Zheng, YF; Chen, YX (2016). "Continental versus oceanic subduction zones". National Science Review. 3 (4): 495–519. doi:10.1093/nsr/nww049.

- Frolich, C. (1989). "The Nature of Deep Focus Earthquakes". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 17: 227–254. Bibcode:1989AREPS..17..227F. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.17.050189.001303.

- Hacker, B.; et al. (2003). "Subduction factory 2. Are intermediate-depth earthquakes in subducting slabs linked to metamorphic dehydration reactions?" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (B1): 2030. Bibcode:2003JGRB..108.2030H. doi:10.1029/2001JB001129.

- Fujie, Gou; et al. (2013). "Systematic changes in the incoming plate structure at the Kuril trench". Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (1): 88–93. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40...88F. doi:10.1029/2012GL054340.

- Stern, R.J. (2004). "Subduction initiation: spontaneous and induced". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 226 (3–4): 275–292. Bibcode:2004E&PSL.226..275S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.08.007.

- Hall, C.E.; et al. (2003). "Catastrophic initiation of subduction following forced convergence across fracture zones". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 212 (1–2): 15–30. Bibcode:2003E&PSL.212...15H. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00242-5.

- Gurnis, M.; et al. (2004). "Evolving force balance during incipient subduction". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 5 (7): Q07001. Bibcode:2004GGG.....5.7001G. doi:10.1029/2003GC000681.

- Keenan, Timothy E.; Encarnación, John; Buchwaldt, Robert; Fernandez, Dan; Mattinson, James; Rasoazanamparany, Christine; Luetkemeyer, P. Benjamin (2016). "Rapid conversion of an oceanic spreading center to a subduction zone inferred from high-precision geochronology". PNAS. 113 (47): E7359–E7366. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E7359K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1609999113. PMC 5127376. PMID 27821756.

- House, M. A.; Gurnis, M.; Kamp, P. J. J.; Sutherland, R. (September 2002). "Uplift in the Fiordland Region, New Zealand: Implications for Incipient Subduction" (PDF). Science. 297 (5589): 2038–2041. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.2038H. doi:10.1126/science.1075328. PMID 12242439.

- Mart, Y., Aharonov, E., Mulugeta, G., Ryan, W.B.F., Tentler, T., Goren, L. (2005). "Analog modeling of the initiation of subduction". Geophys. J. Int. 160 (3): 1081–1091. Bibcode:2005GeoJI.160.1081M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2005.02544.x.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Goren, L.; E. Aharonov; G. Mulugeta; H. A. Koyi; Y. Mart (2008). "Ductile Deformation of Passive Margins: A New Mechanism for Subduction Initiation". J. Geophys. Res. 113: B08411. Bibcode:2008JGRB..11308411G. doi:10.1029/2005JB004179.

- Stern, R.J.; Bloomer, S.H. (1992). "Subduction zone infancy: examples from the Eocene Izu-Bonin-Mariana and Jurassic California arcs". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 104 (12): 1621–1636. Bibcode:1992GSAB..104.1621S. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1992)104<1621:SZIEFT>2.3.CO;2.

- Arculus, R.J.; et al. (2015). "A record of spontaneous subduction initiation in the Izu–Bonin–Mariana arc" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 8 (9): 728–733. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..728A. doi:10.1038/ngeo2515.

- Yin, A. (2012). "An episodic slab-rollback model for the origin of the Tharsis rise on Mars: Implications for initiation of local plate subduction and final unification of a kinematically linked global plate-tectonic network on Earth". Lithosphere. 4 (6): 553–593. Bibcode:2012Lsphe...4..553Y. doi:10.1130/L195.1.

- Harding, Stephan (2006). Animated Earth Science, Intuition and Gaia. Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-933392-29-5.

- Xu, Cheng; Kynický, Jindřich; Song, Wenlei; Tao, Renbiao; Lü, Zeng; Li, Yunxiu; Yang, Yueheng; Miroslav, Pohanka; Galiova, Michaela V.; Zhang, Lifei; Fei, Yingwei (2018). "Cold deep subduction recorded by remnants of a Paleoproterozoic carbonated slab". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 2790. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.2790X. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05140-5. PMC 6050299. PMID 30018373.

- Stern, Robert J. (2005). "Evidence from ophiolites, blueschists, and ultrahigh-pressure metamorphic terranes that the modern episode of subduction tectonics began in Neoproterozoic time". Geology. 33 (7): 557–560. Bibcode:2005Geo....33..557S. doi:10.1130/G21365.1.

- Palin, Richard M.; White, Richard W. (2016). "Emergence of blueschists on Earth linked to secular changes in oceanic crust composition". Nature Geoscience. 9 (1): 60. Bibcode:2016NatGe...9...60P. doi:10.1038/ngeo2605.

- "Volcanic arcs form by deep melting of rock mixtures: Study changes our understanding of processes inside subduction zones". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- Bletery, Quentin; Thomas, Amanda M.; Rempel, Alan W.; Karlstrom, Leif; Sladen, Anthony; Barros, Louis De (2016-11-25). "Mega-earthquakes rupture flat megathrusts". Science. 354 (6315): 1027–1031. Bibcode:2016Sci...354.1027B. doi:10.1126/science.aag0482. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27885027.

- "Subduction zone geometry: Mega-earthquake risk indicator". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- Garcia-Castellanos, D.; M. Torné; M. Fernàndez (2000). "Slab pull effects from a flexural analysis of the Tonga and Kermadec Trenches (Pacific Plate)". Geophys. J. Int. 141 (2): 479–485. Bibcode:2000GeoJI.141..479G. doi:10.1046/j.1365-246x.2000.00096.x.

- "Atlas of the Underworld | Van der Meer, D.G., van Hinsbergen, D.J.J., and Spakman, W., 2017, Atlas of the Underworld: slab remnants in the mantle, their sinking history, and a new outlook on lower mantle viscosity, Tectonophysics". www.atlas-of-the-underworld.org. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- Matthews, John A., ed. (2014). Encyclopedia of Environmental Change. 1. Los Angeles: SAGE Reference.

- Zheng, YF; Chen, RX; Xu, Z; Zhang, SB (2016). "The transport of water in subduction zones". Science China Earth Sciences. 59 (4): 651–682. doi:10.1007/s11430-015-5258-4.

- W. P. Schellart; D. R. Stegman; R. J. Farrington; J. Freeman & L. Moresi (16 July 2010). "Cenozoic Tectonics of Western North America Controlled by Evolving Width of Farallon Slab". Science. 329 (5989): 316–319. Bibcode:2010Sci...329..316S. doi:10.1126/science.1190366. PMID 20647465.

- Bletery, Quentin; Thomas, Amanda M.; Rempel, Alan W.; Karlstrom, Leif; Sladen, Anthony; De Barros, Louis (2016-11-24). "Fault curvature may control where big quakes occur, Eurekalert 24-NOV-2016". Science. 354 (6315): 1027–1031. Bibcode:2016Sci...354.1027B. doi:10.1126/science.aag0482. PMID 27885027. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- Lallemand, Serge; Heuret, Arnauld; Boutelier, David (8 September 2005). "On the relationships between slab dip, back-arc stress, upper plate absolute motion, and crustal nature in subduction zones" (PDF). Geochemistry Geophysics Geosystems. 6 (9): Q09006. Bibcode:2005GGG.....609006L. doi:10.1029/2005GC000917.

- Tsang, Man-Yin; Bowden, Stephen A.; Wang, Zhibin; Mohammed, Abdalla; Tonai, Satoshi; Muirhead, David; Yang, Kiho; Yamamoto, Yuzuru; Kamiya, Nana; Okutsu, Natsumi; Hirose, Takehiro (2020-02-01). "Hot fluids, burial metamorphism and thermal histories in the underthrust sediments at IODP 370 site C0023, Nankai Accretionary Complex". Marine and Petroleum Geology. 112: 104080. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2019.104080. ISSN 0264-8172.

- "USGS publishes a new blueprint that can help make subduction zone areas more resilient". www.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- Hafemeister, David W. (2007). Physics of societal issues: calculations on national security, environment, and energy. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-387-95560-5.

- Kingsley, Marvin G.; Rogers, Kenneth H. (2007). Calculated risks: highly radioactive waste and homeland security. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-7546-7133-6.

- "Dumping and Loss overview". Oceans in the Nuclear Age. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "Storage and Disposal Options. World Nuclear Organization (date unknown)". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2012.

- Lallemand, S (1999). La Subduction Oceanique (in French). Newark, New Jersey: Gordon and Breach.

- Stern, R.J. (1998). "A Subduction Primer for Instructors of Introductory Geology Courses and Authors of Introductory Geology Textbooks". Journal of Geoscience Education. 46 (3): 221–228. Bibcode:1998JGeEd..46..221S. doi:10.5408/1089-9995-46.3.221.

- Stern, R.J. (2002). "Subduction zones". Reviews of Geophysics. 40 (4): 1012. Bibcode:2002RvGeo..40.1012S. doi:10.1029/2001RG000108.

- Tatsumi, Y. (2005). "The Subduction Factory: How it operates on Earth". GSA Today. 15 (7): 4–10. doi:10.1130/1052-5173(2005)015[4:TSFHIO]2.0.CO;2.

- Zheng, YF; Chen, YX (2016). "Continental versus oceanic subduction zones". National Science Review. 3 (4): 495–519. doi:10.1093/nsr/nww049.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Subduction. |

| The Wikibook Historical Geology has a page on the topic of: Subduction |

| Look up subduction in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Animation of a subduction zone.

- From the Seafloor to the Volcano's Top Video about the work of the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 574 Volatiles and Fluids in Subduction Zones in Chile by GEOMAR I Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel.

- Plate Tectonics Basics 1 - Creation and Destruction of Oceanic Lithosphere, University of Texas at Dallas (~ 9 minutes long).