SS Storstad

Storstad was a steam cargo ship built in 1910 by Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd of Newcastle for A. F. Klaveness & Co of Sandefjord. The ship was primarily employed as an ore and coal carrier doing tramp trade during her career. She is best known for accidentally ramming and sinking the ocean liner RMS Empress of Ireland in 1914, killing over 1,000 people.

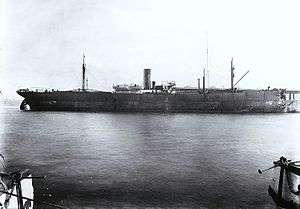

Storstad at Montreal in 1914, soon after colliding with the Empress of Ireland. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Storstad |

| Owner: | |

| Operator: | A/S "Maritim" (1911-1914) |

| Builder: | Armstrong, Whitworth & Co, Newcastle |

| Yard number: | 824 |

| Launched: | 4 October 1910 |

| Commissioned: | January 1911 |

| Homeport: | Kristiania |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | Sunk, 8 March 1917 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Cargo Ship |

| Tonnage: |

|

| Length: | 440 ft 0 in (134.11 m) |

| Beam: | 58 ft 1 in (17.70 m) |

| Depth: | 24 ft 6 in (7.47 m) |

| Installed power: | 447 Nhp[1] |

| Propulsion: | North Eastern Marine Engineering Co 3-cylinder triple expansion |

| Speed: | 13.0 knots |

Design and Construction

Storstad was laid down at Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Low Walker shipyard in Newcastle and launched on 4 October 1910 (yard number 824). As the ship was being launched, she struck a nearby steamship SS Dardania from Trieste, and had her stern damaged.[2][3] After successful completion of sea trials, during which the vessel was able to reach speed of 13.0 knots (15.0 mph; 24.1 km/h), Storstad was handed over to her owners and fully commissioned in January 1911. To operate the vessel, she was transferred to a separate company, Aktieselskabet "Maritim", owned by A. F. Klaveness.

The ship was built on the Isherwood longitudinal framing principle, and at the time of her launch was the largest vessel to be constructed in this manner. The ship was specifically designed for coal and iron ore carriage, and had very large hatches built, with 10 powerful winches installed for quick cargo discharge. As built, the ship was 440 feet 0 inches (134.11 m) long (between perpendiculars) and 58 feet 1 inch (17.70 m) abeam, a mean draft of 24 feet 6 inches (7.47 m).[1] Storstad was assessed at 6,028 GRT, 3,561 NRT and 10,650 DWT.[1] The vessel had a steel hull, and a single 447 nhp triple-expansion steam engine, with cylinders of 28 1⁄2-inch (72 cm), 47-inch (120 cm), and 78-inch (200 cm) diameter with a 54-inch (140 cm) stroke, that drove a single screw propeller, and moved the ship at up to 13.0 knots (15.0 mph; 24.1 km/h).[1]

Operational history

Upon delivery, Storstad departed on January 31, 1911 for her maiden voyage from Newcastle for Narvik and arrived there on February 4.[4][5] The vessel loaded 9,609 tons of iron ore and sailed for Philadelphia on February 11 reaching it on March 7. At the time, this was the largest cargo of iron ore unloaded in Philadelphia from a single ship.[6] Storstad then proceeded to Jacksonville where she took on 6,500 tons of phosphate rock on March 17, then continued on to Savannah and loaded 8,071 bales of cotton and departed for Hamburg on March 28.[7][8] Upon return from Europe on May 20, 1911 the ship was chartered to transport iron ore and coal from Wabana and North Sydney to Montreal and other ports along St. Lawrence River through the end of navigational season in late November.

In November 1911 the vessel was chartered for one trip to South America by the Barber Line. Storstad left New York on December 3, 1911 and arrived in Buenos Aires on December 30, after a call at Montevideo. She then continued on to Rosario and from there sailed out back to New York. Upon arrival, the vessel was chartered by the Lamport & Holt Line for one trip to Manchester. Storstad loaded general cargo, including 1,900 bales of cotton and some food supplies, including cottonseed oil, lard and bacon, and left New York on April 21, 1912.[9] The ship arrived in Liverpool on May 4 and upon discharging her cargo, sailed back to North America to resume her iron ore and coal trade in Canada.

After the end of navigational season in December 1912, Storstad was chartered by Gans Steamship Line and sailed to Tampa Bay, loaded 3,213 tons of phosphate pebble and then sailed to Port Eads, arriving there on December 20. The ship took on more cargo and then sailed for Antwerp arriving there on January 22, 1913. During her journey Storstad encountered some rough weather, and arrived in port with damage about her decks, including washed overboard portion of the deckload, and some deck equipment and covers. Her No. 5 hold was also full of water.[10] The ship arrived in Philadelphia on February 28 with iron ore from Narvik and after unloading continued to Florida. Storstad loaded 5,600 tons of phosphate pebble on March 19 at Boca Grande, then continued to Galveston where she took on 13,097 bales of cotton and departed for Hamburg on March 25.[11][12] After finishing her European charter, the ship returned to her usual Canadian trade in May 1913.

Upon fulfillment of her summer obligations, Storstad arrived at Norfolk on December 20, 1913 to load a cargo of grain bound for Italy. The vessel left on December 26 for Genoa, which she reached on January 16, 1914.[13][14] On her return journey, the ship sailed via Roses and Lisbon and arrived at Philadelphia on March 5 with a cargo of cork.

Upon unloading, Storstad sailed for Norfolk where she loaded 9,700 tons of coal plus 1,100 tons in bunkers and departed for Venice on March 20.[15] The vessel arrived in Italy on April 10, and upon discharging her cargo departed for Sydney arriving there on May 12, 1914. The vessel was chartered by the Dominion Coal Company to transport coal between Sydney and Montreal for the duration of summer navigational season.

Empress of Ireland disaster

On May 28, 1914 at 16:27 RMS Empress of Ireland, commanded by Captain Henry Kendall, departed from Quebec City with 1,057 passengers and 420 crew members on board bound for Liverpool. At around 01:30 on May 29 the liner, being just downstream of Rimouski came close to the shore to drop off her pilot near Father Point, and continued down the Saint Lawrence River. At the same time, Storstad who sailed from Sydney to Quebec loaded with about 10,400 tons of coal on May 26, was a short distance away down the river on her way to pick up the pilot. At around 01:38 a lookout on Empress of Ireland observed a ship off the starboard side about six miles east. Captain Kendall ordered to alter the course slightly in order to pass the oncoming ship starboard to starboard. As the course was changed, a thick fog bank rolled in and the liner was ordered Full Astern and three short blasts were given indicating she was reversing. Storstad replied with one long whistle which appeared to be coming from the starboard side.

He then ordered Full Stop and gave two more blasts, informing the oncoming vessel that Empress of Ireland was dead in the water, Storstad, with First Officer Alfred Toftenes on duty, again responded with one long blast. The watch crew on Storstad initially observed the liner green light on their port side and assumed she would continue to hold her course and pass green-to-green. However, as the liner approached, the freighter's crew sighted the lights moving as if the oncoming ship was making a maneuver changing her course. First Officer Toftenes assumed the oncoming ship was trying to pass them red-to-red instead, and ordered a slight change of course to port and stopped the engines. Fearing the current would carry his ship into the liner's path he soon ordered the engines to be restarted.

Around 01:55 Empress of Ireland crew suddenly saw Storstad appear out of the fog, heading directly for them. Moments later, Storstad and Empress of Ireland collided at around a 40° angle, with the much sturdier Storstad tearing a roughly 16-ft. wide gash in the liner's starboard side between her funnels and immediately shutting down the liner's engines. Captain Kendall, hoping to use Storstad as a plug, directed the freighter by megaphone to keep going Full Ahead, but due to her onward momentum and the strong current, Empress of Ireland kept slowly moving forward, while Storstad started drifting sideways and backwards, and the two vessels soon separated. As the ships moved apart, the water gushed in at a rate of about 60,000 gallons per second, quickly filling the liner, whose watertight doors were not closed. Fourteen minutes later, Empress of Ireland sank to the riverbed, taking 1,012 people down with her.

Due to the rapidity of the sinking, only 7 lifeboats were lowered from the liner. Storstad stood by and assisted the survivors, lowering her own lifeboats and pulling 485 people from the ice cold waters of the river. Twenty of them would later die from hypothermia on board the freighter. Another steamship, SS Lady Evelyn, came by later to help with the rescue and took the survivors to Rimouski. Storstad had her bow smashed in and twisted but managed to limp into the port of Montreal where she was detained.[16]

The Canadian Pacific Railway, which owned Empress of Ireland, filed a $2,000,000 lawsuit for damages against A. F. Klaveness & Co, the owners of Storstad.[17][18] A. F. Klaveness & Co. could not pay the $2,000,000, resulting in the Storstad itself being awarded to the CPR as recompense. The CPR sold the Storstad to Prudential Trust, an insurance company acting on behalf of A. F. Klaveness & Co., for $175,000.[19]

Loss

On 8 March 1917 during World War I, Storstad was sunk in the Atlantic Ocean 45 nautical miles (83 km) south west of the Fastnet Rock (51°20′N 11°50′W) by SM U-62 of the German Imperial Navy. Three crew members of Storstad were lost.[20]

Notes

- Lloyd's Register, Steamships and Motorships. London: Lloyd's Register. 1911–1912.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "Storstad". Norges Sjøfartstidende. 6 October 1910. p. 2.

- "Launches and Trial Trips". Marine Engineer. 33. November 1910. p. 141.

- "Skibsmeldinger". Kysten. 2 February 1911. p. 3.

- "Meldinger fra Rederne". Norges Sjøfartstidende. 7 February 1911. p. 3.

- "Selected Trade News". The Bulletin of the American Iron and Steel Association. 45 (4). Philadelphia, PA. 25 March 1911. p. 30.

- "Shipments of Phosphate Rock, 1911". American Fertilizer. 36 (2). 27 January 1912. p. 37.

- "Shipping News". The Commercial and Financial Chronicle. 92 (2388). 1 April 1911. p. 891.

- "Shipping News". The Commercial and Financial Chronicle. 94 (2444). 27 April 1912. p. 1197.

- "Schiffs-Unfälle". Hamburgischer Correspondent und neue hamburgische Börsen-Halle. 23 January 1913. p. 45.

- "Shipments of Phosphate Rock, 1912". American Fertilizer. 38 (8). 19 April 1913. p. 49.

- "Shipping News". The Commercial and Financial Chronicle. 96 (2492). 29 March 1913. p. 960.

- "Meldinger fra rederne". Norges Handels og Sjøfartstidende. 29 December 1913. p. 7.

- "Skibsliste". Morgenbladet. 17 January 1914. p. 6.

- "Coal Exports from Norfolk". The Black Diamond. 52 (14). 4 April 1914. p. 279.

- "Official Statement Defending the Storstad Says She Had Right of Way and Tried to Avoid Collision," The New York Times, 1 June 1914.

- "Defense of the Collier's Captain." The Independent [New York] 8 June 1914, 78th ed.: 443. Print.

- "Canadian Pacific Ry. Co. v. S.S. Storstad - SCC Cases (Lexum)". Scc-csc.lexum.com. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- "Storstad Bought at Montreal Sale." Toronto Sunday World 8 July 1914, 34th ed.: 6. Print.

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "Ships hit during WWI: Storstad". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

References

- Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada, RG 12, Transport, vol. 1245, dossier « Empress of Ireland »

- Dictionary of Disaster at Sea during the Age of Steam, page 667

- Ship history, page 32, item 116

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Storstad (ship, 1910). |