Stern sculling

Stern sculling is the use of a single oar over the stern of a boat to propel it with side-to-side motions that create forward lift in the water.[1] It is distinguished from sculling, which is rowing with two oars on either side of the boat [2] and from sweep rowing, whereby each boat crew member employs a single oar, complemented by another crew member on the opposite side with an oar, usually with each pulling an oar with two hands.[3]

Overview

Stern sculling is the process of propelling a watercraft by moving a single, stern-mounted oar from side to side while changing the angle of the blade so as to generate forward thrust on both strokes. The technique is very old and its origin uncertain, though it is thought to have developed independently in different locations and times. It is known to have been used in ancient China,[4] and on the Great Lakes of North America by pre-Columbian Americans.

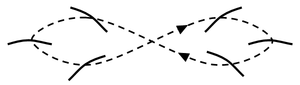

In stern sculling, the oar pivots on the boat's stern, and the inboard end is pushed to one side with the blade turned so that it generates forward thrust; it is then twisted so that when pulled back on the return stroke, the blade also produces forward thrust. Backward thrust can also be generated by twisting the oar in the other direction and rowing. Steering, as in moving coxless sculling shells in crew, is accomplished by directing the thrust. The oar normally pivots in a simple notch cut into—or rowlock mounted on— the stern of the boat, and the sculler must angle the blade, by twisting the inboard end of the oar, to generate the thrust that not only pushes the boat forward but also holds the oar in its pivot. Specifically, the operation of the single sculling (oar) is unique as turning the blade of the oar in figure 8 motions operates them. It is not hoisted in and out of the water like any other traditional oars. The objective is to minimize the movement of the operator's hands, and the side-to-side movement of the boat, so the boat moves through the water slowly and steadily. This minimal rotation keeps the water moving over the top of the blade and results in forces that transfer to the multi directional row-lock, or pivoting mount, on the side of the hull thus pushing the boat forward. Steering the boat is a matter of rotating the oar to produce more thrust on a push or pull of the oar, depending upon which way the operator wants to go.

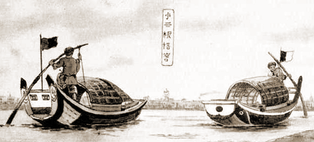

China

The Chinese "yuloh"[5] (from Chinese: 摇 橹; pinyin: yáolǔ; Wade–Giles: yaolu) is a large, heavy sculling oar with a socket on the underside of its shaft which fits over a stern-mounted pin, creating a pivot which allows the oar to swivel and rock from side to side. The weight of the oar, often supplemented by a rope lashing, holds the oar in place on the pivot. The weight of the outboard portion of the oar is counterbalanced by a rope running from the underside of the handle to the deck of the boat. The sculler mainly moves the oar by pushing and pulling on this rope, which causes the oar to rock on its pivot, automatically angling the blade to create forward thrust. This system allows multiple rowers to operate one oar, allowing large, heavy boats to be rowed if necessary. The efficiency of this system gave rise to the Chinese saying "a scull equals three oars".

In crew

Single-oar sculling can occur in competitive rowing when a sweep boat is locked-on at the starting line of a race and the coxswain needs to adjust the direction the boat is pointed in. In order to accomplish this without pulling the boat away from the starting line, the coxswain will command a rower in the bow half of the boat to "scull" the blade of the rower in the seat behind them. By maneuvering the boat in this manner, the coxswain will be able to adjust the point of the boat without disconnecting from the starting line.[6]

Modern use

Modern sculling vessels come in many shapes and sizes and range from being traditional cargo barges and fishing boats to being basic or fun modes of transportation. Either way, they are typically most identifiable by their often side-mounted, unidirectional oar-locks and oars, which allow the operator, ideally, to use one hand to operate the boat. One of the greater attractions to these vessels is that they are easy and inexpensive to operate.[7] The typical modern barge-shaped and "flats"-style boats are still made from materials ranging from a variety of wood products, fibreglass, reinforced concrete, or metals.[8] Some are simply converted old motor boats. The traditional advantages of the smaller sculling craft as a hunting boat are that the operator can quietly sneak up upon fish and fowl without splashing or otherwise disturbing the still calm of the water. New commercially available single sculling hunting boats use very light materials and slick shapes for greater speeds and responsiveness.[9] Notably, the oars of the more modern single sculling vessels are now more typically mounted to pivot off one side of the boat. The operator can face either forward or aft.

Sculling in swimming

Sculling can also refer to a specific swimming drill in which the arms and hands of the swimmer are used to propel them forwards or backwards through the water. The swimmer is typically face-down in the water with their arms extended above their head or down by their hips, depending on the technique. In this position, the swimmer moves their cupped hands in a constant back-and-forth motion: wrists down with palms facing forward to move backwards, wrists slightly up with palms facing slightly back to move forward.[10]

See also

- Gondola

- Oars

- Sampan

- Single scull

- Watercraft rowing

References

- Mcgrail, Sean (11 June 2014). Ancient Boats in North-West Europe: The Archaeology of Water Transport to AD 1500. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-88238-1.

- Woodgate, Walter Bradford (1874). Oars and Sculls. J. Watson.

- Stevens, Arthur Wesselhoeft (1906). Practical Rowing with Scull and Sweep. New York: Little, Brown, & Co. p. 90.

- "The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China" by Joseph Needham, Colin A. Ronan, Cambridge University Press, 1978 ISBN 0-521-31560-3, ISBN 978-0-521-31560-9

- "Cranks with Planks". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- "How to Scull". Jesterinfo.org. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- Chad Dolbeare (22 February 1999). "Scull Boats: Waterfowl Stealth Hunting". LiveOutdoors. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- "What Are the Four Different Sculling Techniques? | Chron.com". Livehealthy.chron.com. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

External links

| Look up sculling in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "How To Scull A Boat" (Good article including several diagrams).

- "Rowing 101" (Much pertinent information about competitive rowing)