Stencil (numerical analysis)

In mathematics, especially the areas of numerical analysis concentrating on the numerical solution of partial differential equations, a stencil is a geometric arrangement of a nodal group that relate to the point of interest by using a numerical approximation routine. Stencils are the basis for many algorithms to numerically solve partial differential equations (PDE). Two examples of stencils are the five-point stencil and the Crank–Nicolson method stencil.

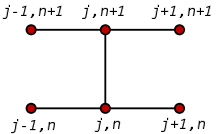

Stencils are classified into two categories: compact and non-compact, the difference being the layers from the point of interest that are also used for calculation.

In the notation used for one-dimensional stencils n-1, n, n+1 indicate the time steps where timestep n and n-1 have known solutions and time step n+1 is to be calculated. The spatial location of finite volumes used in the calculation are indicated by j-1, j and j+1.

Etymology

Graphical representations of node arrangements and their coefficients arose early in the study of PDEs. Authors continue to use varying terms for these such as "relaxation patterns", "operating instructions", "lozenges", or "point patterns".[1][2] The term "stencil" was coined for such patterns to reflect the concept of laying out a stencil in the usual sense over a computational grid to reveal just the numbers needed at a particular step.[2]

Calculation of coefficients

The finite difference coefficients for a given stencil are fixed by the choice of node points. The coefficients may be calculated by taking the derivative of the Lagrange polynomial interpolating between the node points,[3] by computing the Taylor expansion around each node point and solving a linear system,[4] or by enforcing that the stencil is exact for monomials up to the degree of the stencil.[3] For equi-spaced nodes, they may be calculated efficiently as the Padé approximant of , where is the order of the stencil and is the ratio of the distance between the leftmost derivative and the left function entries divided by the grid spacing.[5]

References

- Emmons, Howard W. (1 October 1944). "The numerical solution of partial differential equations" (PDF). Quarterly of Applied Mathematics. 2 (3): 173–195. doi:10.1090/qam/10680. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Milne, William Edmund (1953). Numerical solution of differential equations (1st ed.). Wiley. pp. 128–131. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- Fornberg, Bengt; Flyer, Natasha (2015). "Brief Summary of Finite Difference Methods". A Primer on Radial Basis Functions with Applications to the Geosciences. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. doi:10.1137/1.9781611974041.ch1. ISBN 9781611974027. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Taylor, Cameron. "Finite Difference Coefficients Calculator". web.media.mit.edu. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Fornberg, Bengt (January 1998). "Classroom Note: Calculation of Weights in Finite Difference Formulas". SIAM Review. 40 (3): 685–691. doi:10.1137/S0036144596322507.

- W. F. Spotz. High-Order Compact Finite Difference Schemes for Computational Mechanics. PhD thesis, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, 1995.

- Communications in Numerical Methods in Engineering, Copyright © 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.