Steindamm (Königsberg)

Steindamm was the oldest quarter of Königsberg, Germany. Its territory is now part of Kaliningrad, Russia.

History

Medieval Steindamm

After the Teutonic Knights conquered the region in 1255, they allowed the creation of a German settlement northwest of their newly built castle. However, this initial settlement was destroyed by Sambians led by Nalube during the 1262 Siege of Königsberg. When the new town of Altstadt south of the castle received its town charter in 1286, the area of the previous settlement was designated as Altstadt's Freiheit suburb and began to be redeveloped.

The resettled area, which became known as Steindamm (stone causeway or embankment) after its main thoroughfare, extended northwest of Königsberg Castle. Medieval Steindamm began at the original southern Steindamm Gate (Steindammsches Tor) by Koggenstraße, traveled north past Steindamm Bridge (Steindammsche Brücke) and the castle's moat, and ended at Altstadt's execution site (the later Heumarkt).[1] Medieval Steindamm contained a substantial population of Old Prussians.[2]

Early modern era

Steindamm received its own court seal from Altstadt's council in 1491.[3] The Dinghaus near the original southern Steindamm Gate served as Steindamm's courthouse from 1491 to 1724.[4] Steindamm was outside of the original medieval walls of Altstadt and the castle; it was first enclosed within the Baroque walls built during the 1620s. By the 17th century Steindamm was bordered by Tragheim to the east, Burgfreiheit to the southeast, Altstadt and Königsberg Castle to the south, and Neuroßgarten to the west. To the north Steindamm extended to the 17th century Baroque city walls, beyond which was Hufen.

By the Rathäusliche Reglement of 13 June 1724, King Frederick William I of Prussia merged Altstadt and Steindamm into the united city of Königsberg.[5] In 1725 Michael Lilienthal listed the suburb's main streets as including the eponymous wide thoroughfare (also known as Steindamm rechte Straße until 1900[1]), Rollberg, Strützel-Gasse, Mönchen-Gasse (later Heinrichsstraße), Todten-Gasse (later Wagnerstraße), Rosen-Gasse, Polnisch-Prediger-Gasse (later Nikolaistraße), the smaller and larger Büttel-Platz (later Strohmarkt and Heumarkt), Walsche-Gasse, and Wall-Gasse.[6] The city's post office was located at Poststraße, which became Burgfreiheit's Junkerstraße to the east.

.png)

Walsche Gasse was named after Pavao Skalić (Skalichius), considered by Königsbergers to be Welsch. Wagnerstraße was named after the director of the University of Königsberg's surgical clinic, Karl Ernst Albrecht Wagner, not Richard Wagner as commonly believed.[7] According to folklore, the hill Rollberg was named after an alleged Duke of Normandy named Rollo. The hill was also known as the Glappenberg; Peter of Dusburg wrote of a Warmian chief named Glappo who was hanged on the hill in 1320.[8]

Later history

Throughout its history, Steindamm Church, the oldest church in the city, served German, Polish, and Lithuanian parishioners. The Hotel de Berlin was a prominent hotel located in Steindamm. By 1890 the area from Neuroßgarten's Wagnerstraße through Steindamm to Tragheimer Pulverstraße was the most densely settled part of the city.[9]

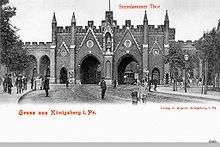

The northern Steindamm Gate (Steindammer Tor), the most architecturally impressive gate in the city walls, was dismantled in 1912 to allow further development in northern Königsberg, as Steindamm was one of the busiest thoroughfares in the city.[10] The arterial road connecting Steindamm and Hufen was known first as Kaiser-Wilhelm-Damm, then Hansaring in 1918, and then Adolf-Hitler-Straße in 1933.[10] Institutions located at the new square, Hansa-Platz (later Adolf-Hitler-Platz), included the Amtsgericht, Landgericht, and Polizeipräsidium.[10] Nearby was the Neues Schauspielhaus.

Steindamm was heavily damaged by the 1944 Bombing of Königsberg and 1945 Battle of Königsberg. The boulevard itself is now part of Leninskiy Prospekt in Kaliningrad.

Notes

- Mühlpfordt, p. 36

- Gause I, p. 117

- Armstedt, p. 50

- Bötticher, p. 236

- Gause II, p. 65

- Bötticher, p. 227

- Mühlpfordt, p. 162

- Mühlpfordt, p. 117

- Armstedt, Heimatkunde p. 22

- Gause II, p. 650

References

- Albinus, Robert (1985). Lexikon der Stadt Königsberg Pr. und Umgebung (in German). Leer: Verlag Gerhard Rautenberg. p. 371. ISBN 3-7921-0320-6.

- Armstedt, Richard (1895). Heimatkunde von Königsberg i. Pr (in German). Königsberg: Kommissionsverlag von Wilhelm Koch. p. 306.

- Bötticher, Adolf (1897). Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler der Provinz Ostpreußen (in German). Königsberg: Rautenberg. p. 395.

- Gause, Fritz (1965). Die Geschichte der Stadt Königsberg. Band I: Von der Gründung der Stadt bis zum letzten Kurfürsten (in German). Köln: Böhlau Verlag. p. 571.

- Gause, Fritz (1968). Die Geschichte der Stadt Königsberg. Band II: Von der Königskrönung bis zum Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkriegs (in German). Köln: Böhlau Verlag. p. 761.

- Mühlpfordt, Herbert Meinhard (1972). Königsberg von A bis Z (in German). München: Aufstieg-Verlag. p. 168. ISBN 3-7612-0092-7.