Steam railcar

A steam railcar is a railcar that is self powered by a steam engine. The first steam railcar was an experimental unit designed and built in 1847 by James Samuel and William Bridges Adams in Britain. In 1848 they made the Fairfield steam carriage that they sold to the Bristol & Exeter Railway, who used it for two years on a branch line.

Origins

The first steam railcar was designed by James Samuel, the Eastern Counties Railway Locomotive Engineer, built by William Bridges Adams in 1847, and trialled between Shoreditch and Cambridge on 23 October 1847. An experimental unit, 12 feet 6 inches (3.81 m) long with a small vertical boiler and passenger accommodation was a bench seat around a box at the back.[1] The following year Samuel and Adams built the Fairfield steam carriage. This was much larger, 31 feet 6 inches (9.60 m) long, and built with an open third class section and a closed second class section. After trials in 1848, it was sold to the Bristol & Exeter Railway and ran for two years on the Tiverton branch.[2]

History by country

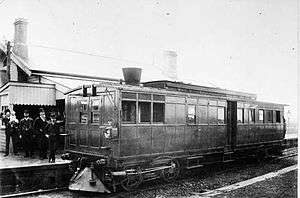

Australia

In 1883 the Victorian Railways purchased the Rowan steam railmotor.[3] A similar unit was imported from Belgium by the South Australian Railways in 1895.

In 1913, Kerr, Stuart and Company built a boiler, shipped it to Australia and the Victorian Railways assembled the Kerr Stuart steam railmotor.

Austria–Hungary

.jpg)

In 1880, Ringhoffer of Prague built a steam railcar for the Österreichische Lokaleisenbahngesellschaft (Austrian local railway). With 32 seats and a maximum speed of 18 kilometres per hour (11 mph), it had been withdrawn by 1900. In the early 20th century, the Imperial Royal Austrian State Railways ordered a railcar with a Serpollet boiler from Esslingen, followed by a number of cars with boilers from Komarek of Vienna and carriages from Ringhoffer. The Niederösterreichische Landesbahnen (Lower Austrian State Railway) also bought cars made by Komarek and Rohrbacher. Most cars had been withdrawn by the end of World War I, and those that remained when Austria-Hungary was divided in 1918 were divided between the Czechoslovak State Railways and the Austrian Federal Railways. All units having been withdrawn by the end of the 1950s, as of 2012 one car is preserved operational at the Czech Railway Museum in Lužná (Rakovník District).[4]

Between 1901 and 1908, Ganz Works of Budapest and de Dion-Bouton of Paris collaborated to build a number of railcars for the Hungarian State Railways together with units with de Dion-Bouton boilers, Ganz steam motors and equipments, and Raba carriages built by the Raba Hungarian Wagon and Machine Factory in Győr. In 1908, the Borzsavölgyi Gazdasági Vasút (BGV), a narrow-gauge railway in Carpathian Ruthenia (today's Ukraine), purchased five railcars from Ganz and four railcars from the Hungarian Royal State Railway Machine Factory with de Dion-Bouton boilers. The Ganz company started to export steam motor railcars to the United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Japan, Russia and Bulgaria.[5][6][7]

Britain

Steam railcars to be built in Britain in the early 20th century for the London & South Western Railway (L&SWR) and before entering passenger service one was lent to the Great Western Railway (GWR) for a trial run in the Stroud Valley between Chalford and Stonehouse in Gloucestershire.[8] Between 1902 and 1911, 197 steam railcars were built, 99 by the GWR.[9]

Introduced either due to competition from the new electric tramways or to provide an economic service on lightly used country branch lines, there were two main designs, either a powered bogie enclosed in a rigid body or an articulated engine unit and carriage, pivoting on a pin. However, with little reserve power steam railcars were inflexible and the ride quality was poor due to excessive vibration and oscillation. Most were replaced by an autotrain, adapted carriages and a push-pull steam locomotive as these were able to haul additional carriages or goods wagons.

After trials in 1924, the London and North Eastern Railway purchased three types of steam railcars from Sentinel-Cammell and Claytons.

| Railway | Number of railcars | Introduced | Withdrawn | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol & Exeter Railway | 1 | 1848 | 1850 | [2] | |

| Joint London, Brighton & South Coast Railway and London & South Western Railway | 2 | 1902 | 1919 | [10] | |

| Barry Railway | 2 | 1903 | 1913 | [11] | |

| Great Western Railway | 99 | 1903-08 | 1935 (many were converted to auto-trailers) |  | [12] |

| Taff Vale Railway | 18 | 1903-06 | early 1920s | .jpg) | [13] |

| Alexandra (Newport and South Wales) Docks and Railway | 2 | 1904 | 1911 1917 | [14] | |

| Midland Railway | 1 | 1904 | 1912?[lower-alpha 1] | [15] | |

| Glasgow and South Western Railway | 2 | 1904–5 | 1915–16 | [17] | |

| London & South Western Railway | 15 | 1904-06 | 1916-19 | [18] | |

| Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway | 18 | 1905-11 | 1927-48 | L&YR railmotors | [19] |

| Great Central Railway | 3 | 1904–5 | 1914 | [15] | |

| South Eastern & Chatham Railway | 8 | 1904-5 | 1914 | [15] | |

| North Staffordshire Railway | 3 | 1905 | 1922 | [20] | |

| London, Brighton & South Coast Railway | 2 | 1905 | 1909 | [20] | |

| Furness Railway | 2 | 1905 | 1914 | [21] | |

| Great North of Scotland Railway | 2 | 1905 | 1909–10 | [22] | |

| Great Northern Railway | 6 | 1905 | 1925-6 | [23] | |

| London & North Western Railway | 6 | 1905-07 | 1948 |  | [24] |

| Isle of Wight Railway | 1 | 1906 | 1912 | [25] | |

| Port Talbot Railway | 1 | 1907 | 1920[lower-alpha 2] | [27] | |

| Rhymney Railway | 2 | 1907 | 1909 1919 | [28] | |

| Cardiff Railway | 2[lower-alpha 3] | 1911 | 1917 | [29] | |

| Nidd Valley Light Railway | 1 | 1920[lower-alpha 4] | 1937 | [30] | |

| Millwall Extension Railway | 3 | 1920[lower-alpha 5] | 1926 | [31] | |

| London & North Eastern Railway | 81 | 1924 | 1947 | .jpg) | [32] |

| London, Midland and Scottish | 14 | 1925-27 | 1947 | [33] | |

| Cheshire Lines Railway | 4 | 1929 | 1944 | [34] | |

| Axholme Joint Railway | 1 | 1930 | 1944 | [34] | |

| Southern Railway | 1 | 1933 | 1936 | [35] | |

Notes

| |||||

Egypt

In 1951 Sentinel and Metro-Cammell built ten 3-car steam railcar units for the Egyptian National Railways. The units were articulated, with an oil-fired boiler supplying steam to two 6-cylinder steam motors. Withdrawn from service in 1962, as of 2012 one unit is under restoration at the Buckinghamshire Railway Centre.[36]

France

At the beginning of the 20th century Société Valentin Purrey patented a steam engine that was used in railcars. Built in Bordeaux by 1903 fifty cars had been built, including 40 to the Compagnie Générale des Omnibus-Paris.[37] Also, Buffaud & Robatel built a steam railcar for the metre gauge Chemin de fer de Kayes au Niger in Mali.

Germany

In 1879 Georg Thomas of the Hessian Ludwig Railway developed a double-decker steam railcar, for which he was granted a patent in 1881. The three-axle vehicle consisted of a single-axle engine unit and a two-axle double-deck carriage part, rigidly coupled together and separable only in the workshop. The Hessian Ludwig Railway built three in 1879-80, followed by the Royal Saxon State Railways, the Oels-Gniezno Railway and the Royal Württemberg State Railways. The Royal Bavarian State Railways built a similar Bavarian MCi in 1882. All had been withdrawn in the early 20th century.

In 1895 the Royal Württemberg State Railways ordered a steam railcar using a Serpollet boiler from Esslingen, followed by six more. At first, their performance was unsatisfactory, until Eugen Kittel of the Württemberg State Railways developed a new firebox. Seventeen were built for the Württemberg State Railways and railcars were also made for the Royal Saxon State Railways, Swiss Northeastern Railway and Imperial Royal Austrian State Railways, and the Grand Duchy of Baden State Railway in 1914-15.

In 1918 the Austrian State Railways unit passed to the Czechoslovak State Railways after Austria-Hungary was divided at the end of World War I. At the end of World War II units were divided between the Deutsche Reichsbahn of East Germany, Deutsche Bundesbahn of West Germany and SNCF of France and all units had been withdrawn by 1953.

In 1906 the Prussian state railways bought two steam railcars, one fired by coal and the other oil, from Hannoversche Maschinenbau AG.

Seven Bavarian MCCi units were built between 1906 and 1908 for the Royal Bavarian State Railways for suburban services in the Munich area, the coach bodies being manufactured by MAN and the engines by Maffei. These had all been withdrawn by the end of the 1920s.

A steam railcar, DR 59, was built by Wismar in 1937 to reduce the dependency on imported diesel or petrol. After the war ownership of the car passed to the Deutsche Reichsbahn of East Germany, and in 1959 was converted into a driving trailer and withdrawn in 1975.

Italy

In 1904 two steam railcars were ordered from Purrey; classified as FS 80 these were withdrawn in 1913.[37] Sixty-five railcars, classified as FS 60, were purchased in 1905 to 1907, but found to be under-powered and sixteen were converted into locomotives.[38] At the 1906 Milan Fair an FS 85 was exhibited and three were purchased, followed by 12 British built FS86s.

In 1936 three railcars using high-pressure steam were purchased and classified ALV72. This were converted into ALn72s three years later.

Mali

_Voiture_automotrice_%C3%A0_vapeur_KNVA_n%C2%B01.jpg)

French manufacturers Buffaud & Robatel built a steam railcar for the metre gauge Chemin de fer de Kayes au Niger in Mali.

New Zealand

In 1925 and 1926 two steam railcars were supplied to New Zealand Railways Department, one from Sentinel and Cammell and the other from Claytons. They were both withdrawn after a few years.

North America

In North America a railcar is known as a Doodlebug. In 1906 the Canadian Pacific Railway had an oil fired steam railcar.[39]

In 1911, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway built a steam-powered railcar combining a Jacobs-Schupert boiler and a Ganz Works power truck in an American Car and Foundry body. The resulting doodlebug was designated M-104. It operated experimentally under its own power for only three months. With the steam machinery removed and an unpowered bogie truck substituted, the car operated as an unpowered combine (combination baggage-coach car) until the 1960s.[40]

Sweden

Steam railcars were used in Sweden in the 1880s.

Switzerland

In 1889 steam railcars were built for the Pilatus Railway, a rack railway in Switzerland with a maximum gradient of 48%.

Cars nos. 1-9 were built by the Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works in Winterthur, followed by No. 10 in 1900 and no. 11 in 1909. The railway was electrified in 1937, and the cars scrapped except for two. Car no. 9 remained until 1981 as a reserve and has since been in the Swiss Transport Museum in Lucerne. Car no. 10 is on permanent loan to the Deutsches Museum in Munich.[41]

In 1902 a steam railcar was built by Maschinenfabrik Esslingen. Not a success, it was rebuilt in 1907 and sold to the Uerikon Bauma Railway. The railcar was withdrawn in 1950 and as of 2012 the railcar is restored.[42]

Notes and references

References

- Rush 1971, p. 16.

- Rush 1971, pp. 16–18.

- Victorian Railways Rolling Stock

- "Steam railcar M 124.001". cdmuszeum.cz. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Railroad Gazette - Volume 37 - Page 296 (printed in 1904)

- Modern Machinery - Volumes 19-20 - Page 206 (Printed in 1906)

- John Robertson Dunlap, Arthur Van Vlissingen, John Michael Carmody: Factory and Industrial Management - Volume 33 - Page 1003 (printed in 1907)

- "First trail in Gloucestershire - Great Western Railway History". Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Jenkinson 1996, p. 257.

- Rush 1971, pp. 22–24.

- Rush 1971, pp. 79–80.

- Rush 1971, p. 39.

- Rush 1971, p. 47.

- Rush 1971, pp. 81–83.

- Rush 1971, pp. 65–66.

- Hedges 1980, p. 136.

- Rush 1971, pp. 93–94.

- Rush 1971, p. 30.

- Rush 1971, p. 51.

- Rush 1971, pp. 72–73.

- Rush 1971, pp. 70–71.

- Rush 1971, pp. 95–97.

- Rush 1971, p. 63.

- Rush 1971, pp. 58–59.

- Rush 1971, pp. 76–77.

- Rush 1971, p. 89.

- Rush 1971, pp. 88–89.

- Rush 1971, pp. 84–85.

- Rush 1971, p. 90.

- Rush 1971, p. 32.

- Rush 1971, p. 33.

- Rush 1971, pp. 119, 123-125.

- Rush 1971, p. 123.

- Rush 1971, p. 124.

- Rush 1971, pp. 121–122.

- "Sentinel-Cammell Steam Railcar No. 5208". BRC Stockbook. 9 October 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- Cruciani, Marcello (May 1999). "Purrey in Italia". i treni (in Italian) (204): 17–21.

- Briano, Italo (1977). Storia delle ferrovie in Italia (in Italian). III. pp. 65–68. OCLC 490069757.

- "Steam Motor Car For the Canadian Pacific Railway". Railway Age: 254–255. August 1906. Accessible online at ebay.com. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Worley, E.D. (1965). Iron Horses of the Santa Fe Trail. US: Southwest Railroad Historical Society.

- Sources:

- R. J. Buckley; W. J. Wyse (1984). Tramways and Light Railways of Switzerland and Austria. Light Rail Transit Association. ISBN 978-0-900433-96-2.

- Chronik der Eisenbahn (in German). Heel Verlag GmbH. 20 December 2005. ISBN 978-3-89880-413-4.

- Moser, Alfred; Winter, Paul (1975). Der Dampfbetrieb der schweizerischen Eisenbahnen, 1847-1966 (in German). Birkhäuser. ISBN 3-7643-0742-0.

Sources and further reading

- Britain

- Hedges, Martin, ed. (1980). 150 Years of British Railways. Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-37655-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkinson, David (1996). History of British Railway Carriages, 1900–53. Atlantic Transport. ISBN 978-1899816033.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rush, R.W (1971). British Steam Railcars. Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-144-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tufnell, R.M. (1984). The British Railcar: AEC to HST. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8529-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Austria-Hungary

The following books are in German

- Adolph Giesl-Gieslingen (1981). Aera nach Golsdorf: Die letzten drei jahrzehnte des osterreichischen Dampflokomotivhaus. Slezak. ISBN 978-3-900134-37-2.

- Alfred Horn; Wilhelm Urbanczik (1972). Dampftriebwagen und Gepäcklokomotiven in Österreich, Ungarn, der Tschechoslowakei und Jugoslawien. Bohmann. ISBN 978-3-7002-0309-4.

- Dieter Bäzold, Rolf Löttgers, Günther Scheingraber u. a.: Preußen-Report, Band 9: Zahnrad- und Schmalspurlokomotiven, Triebwagen. Eisenbahn-Journal, Hermann Merker Verlag, Fürstenfeldbruck 1996 Modelleisenbahner Nr. 4: Preußische Dampftriebwagen der Bauart Stoltz, April 1988, S. 17–20

- Dieter Zoubek (2004). Erhaltene Dampflokomotiven in und aus Österreich 2004. Zoubek, Dieter. ISBN 978-3-200-00174-9.

- Helmut Griebel; Josef Otto Slezak; Hans Sternhardt (1 December 1985). BBÖ Lokomotiv-Chronik 1923-1938. Slezak. ISBN 978-3-85416-026-7.

- Johann Blieberger; Josef Pospichal (2011). Enzyklopädie der kkStB-Triebfahrzeuge, Band 4: Die Reihen 83 bis 100, Schmalspur- und nicht mit Dampf betriebene Bauarten. bahnmedien.at. ISBN 978-3-9502648-8-3.

- Friedrich Slezak; Josef Otto Slezak (1981). Vom Schiffskanal zur Eisenbahn: Wiener Neustädter kanal and Aspangbahn. Verlag Josef Otto Slezak. ISBN 978-3-900134-72-3.

- Verzeichnis der Lokomotiven, Tender, Wasserwagen und Triebwagen der k. k. österreichischen Staatsbahnen und der vom Staate betriebenen Privatbahnen nach dem Stande vom 30. Juni 1917, 14. Auflage, Verlag der k. k. österreichischen Staatsbahnen, Wien, 1918

The following books are in Czech

- Karel Beneš (1995). Železnice na Podkarpatské Rusi. Nakl. dopravy a turistiky. ISBN 978-80-85884-32-6.

- Karel Just (2001). Parní lokomotivy na úzkorozchodných tratích ČSD. Vydavatelství dopravní literatury Luděk Čada. ISBN 978-80-902706-5-7.

The following books are in Hungarian

- Ernő Lányi (1984). Nagyvasúti vontatójárművek Magyarországon. Közlekedési Dokumentációs Vállalat. ISBN 978-963-552-161-6.

- Villányi György (1996). Gőzmotorkocsik és kismozdonyok. Magyar Államvasutak Rt.

- Germany

These sources are in German

- Peter Henkel (1985). "Der Dampftriebwagen nach Thomas". Die Bahn und ihre Geschichte = Schriftenreihe des Landkreises Darmstadt-Dieburg 2. Darmstadt: Georg Wittenberger / Förderkreis Museen und Denkmalpflege Darmstadt-Dieburg).

- Deutsche Reichsbahn (1935). Hundert Jahre deutsche Eisenbahnen. Jubiläumsschrift zum hundertjährigen Bestehen der deutschen Eisenbahnen.

- Lutz Uebel; Wolfgang Richter (1994). MAN - 150 Jahre Schienenfahrzeuge aus Nürnberg.

- Peter Zander (1989). "Doppelstöckige Dampftriebwagen der Bauart Thomas". modell eisenbahner. Eisenbahn-Modellbahn-Zeitschrift.

- Hermann Lohr (1988). Lokomotiv Archiv Württemberg. Transpress. ISBN 978-3-344-00222-0.

- Hermann Lohr (1988). Lokomotiv Archiv Baden. Transpress. ISBN 978-3-344-00210-7.

- Wolfgang Valtin (1992). Verzeichnis aller Lokomotiven und Triebwagen: Dampflokomotiven und Dampftriebwagen. Transpress. ISBN 978-3-344-70740-8.

- Werner Willhaus (September 2008). Kittel-Dampftriebwagen: Innovation des Nahverkehrs vor über 100 Jahren. EK-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-88255-106-8.

- Rainer Zschech (1993). Dampf- und Verbrennungstriebwagen: Deutsche Reichsbahn-Gesellschaft, Deutsche Reichsbahn, Deutsche Bundesbahn. Transpress. ISBN 978-3-344-70766-8.

- Erich Preuß; Reiner Preuß (1991). Sächsische Staatseisenbahnen. Transpress. ISBN 978-3-344-70700-2.

- Fritz Näbrich, Günter Meyer, Reiner Preuß: Lokomotivarchiv Sachsen 2, Transpress VEB Verlag für Verkehrswesen, Berlin, 1983

- Krauss-Maffei, Deutsches Museum Munich (ca. 1977): Lokomotiven im Deutschen Museum

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steam railcars. |