State of Revolution

State of Revolution is a two act play by Robert Bolt, written in 1977.[1] It deals with the Russian Revolution of 1917 and Civil War, the rise to power of Vladimir Lenin, and the struggles of his chief lieutenants – namely Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky – to gain power under Lenin in the chaos of the Revolution.[2][3]

| State of Revolution | |

|---|---|

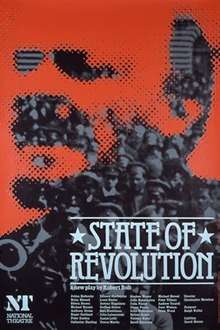

Original National Theatre poster | |

| Written by | Robert Bolt |

| Date premiered | 3 May 1977 |

| Place premiered | Birmingham Repertory Theatre |

| Original language | English |

The play originally opened at the Repertory Theatre in Birmingham on 3 May 1977, and the production then moved to the Lyttelton Theatre in London, where it opened on 18th May.[4]

Despite the painstaking work put into the show by Bolt (he spent almost three years researching the Revolution and then editing the script), State of Revolution was at best a modest success. He was particularly criticised for having a play which, many felt, lacked Bolt's usual humour and a clear point (see Times review below). Others criticised the play for depicting the Russian characters in too much of an Anglicized manner. The play received its share of positive reviews as well, but was ultimately not a box-office success.[3] It would prove to be Bolt's last stage production, though he would write several more film scripts.

Bolt himself was never satisfied with the play, feeling that he had failed to create strong and sympathetic lead characters. In the late 1970s (according to Bolt's biographer, Adrian Turner), Charlton Heston attempted to produce a film version, but Bolt himself talked Heston out of it.

Play synopsis

Act I

The play is framed by an address being given by Anatoly Lunacharsky to a group of Young Communists at an unspecified date in the future, on the anniversary of Lenin's death. Lunacharsky gives a speech which solidly toes the Communist Party line about the Revolution and its leaders, Joseph Stalin, Lenin, and Trotsky.

The narrative begins in Capri in 1910 at a meeting of several exiled Communist leaders – including Lenin, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Alexey Gorky, and Alexandra Kollontai. Lunacharsky's speech dissolves into a speech being given at this meeting, being proposed as a Communist thesis; all present support it except Lenin, who dismisses it as "shit". Lenin thinks his beliefs in supporting "the human ethic" is ridiculous and "merits abuse", and dismisses the majority opinion against him: "It's not a school for revolutionary activists you're getting ready here – it's a school in parliamentary procedure." Lenin continues to draw conflict with his peers and is depicted as being driven purely by ideology rather than any idealism.

The play cuts ahead to 1917, when Russia's struggles in World War I lead to the collapse of the Czar's government. The Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky wants to continue the war, but the radical Bolsheviks urge an end to the war at all costs while others in the Party – including Stalin – urge continuation of the fighting on the grounds that Russia's defeat will lead to the re-establishment of the Czar. When Lenin arrives in Finland Station, he is initially greeted warmly – until he calls for the establishment of a socialist regime and an end to the war – even if it means a German victory. Later on, the situation comes to a head as the Russian army finally collapses, and Lenin recruits Zhelnik – commander of the Kronstadt Sailors' Soviet – in his plan to capture Petrograd for the Bolsheviks.

Lenin instantly sets about organising his government, placing Trotsky, Stalin, Kollontai, and Lunacharsky in high-ranking positions. The government leaders proclaim a new system of freedoms and reforms, much to the delight of the Russian people. Trotsky is, however, forced to negotiate a peace treaty with the Germans and is unable to bargain on his own terms – apparently under the delusion that the German soldiers will desert and join the Revolution. The first signs of tension appear when Stalin refers to Trotsky – who volunteers to organise the Red Army – as "our Bonaparte", greatly insulting Trotsky for this suggestion of counter-revolutionary disloyalty. At this time, Dzerzhinsky is appointed head of the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. At the end of the act, in a private conversation, Lenin tells Stalin that he is "the most useful Comrade on the whole Committee."

Act II

Act II begins as Zhelnik angrily meets with Lenin, his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya, and Kollontai, reporting an incident where he and his men were ordered to massacre a group of peasants who would not turn over their stores of grain. Lenin argues the measure was justified because peasants are likely to be counter-revolutionaries, and Zhelnik's protests – "We're all – peasants!" – fall on deaf ears. Shortly thereafter, Lenin meets with Fanya Kaplan, a member of the Peasant Revolutionary Party, who protests the exclusion of all non-Bolshevik parties from the Soviets. At the end of the conversation, Kaplan produces a pistol and shoots Lenin, regretting only that she failed in her attempt.

The assassination coincides with the outbreak of full-scale Civil War and intervention of foreign powers, leading Dzerzhinsky to institute the Red Terror against all Russians suspected of being counter-revolutionary. At this time, Lunacharasky protests to Dzerzhinsky the extravagant production demands of the government – in turn, she is warned by him against protesting.

Zhelnik and the other Kronstadt sailors organise a revolt against the Soviet government. Trotsky and Kollontai meet with the sailors and refuse to give in to their demands; Trotsky resorts to violent force to put down the rebellion. Shortly after, Trotsky comes into conflict with Lenin and Stalin for proposing a limited market economy – which Stalin twists into being counter-revolution. At this point, Stalin proposes that the Party must be expunged of its less loyal members, and advocates a purge – which is supported by Lenin. The accusations against Trotsky grow, until even Lenin is almost convinced of his possible treachery. Gorky confronts Lenin over his treatment of Trotsky. Gorky angrily protests the imprisonment of provably innocent individuals by the Cheka, and Lenin accuses him too of being a traitor. Lenin then has a stroke, leaving him incapacitated and Stalin and Trotsky to fill in the void.

Stalin and Dzerzhinsky meet with Victor Mdvani, leader of the Georgian Communist Party, and interrogate him over disloyal statements made in a private letter and his alleged refusal to support Lenin's policies of collectivisation and unification in his republic. At the end of this meeting, a Cheka officer – Pratkov – is identified as Captain Draganov, a high-ranking member of the Czar's secret police, and Stalin orders him executed.

A crippled but still strong-willed Lenin speaks with his wife, expressing his dislike and distrust of Stalin. He plans to have Trotsky give a speech denouncing Stalin, but Trotsky is ill and Stalin ends up giving the same speech about Trotsky. Lenin dies shortly thereafter.

After Lenin's death, his colleagues organise a vote, hoping to have Trotsky appointed as Lenin's successor. Despite his distaste for Stalin, Trotsky refuses to brand him a counter-revolutionary, and Stalin wins the vote. The play ends with Lunacharsky's speech – discussing Trotsky's fall from grace and saying that the Revolution should not be remembered as a "pageant of Great Men", but rather as an inevitable event which was served by Lenin, Stalin, and others.

Original cast

- Brian Blessed ... Gorky

- Michael Bryant ... Vladimir Lenin

- Anthony Douse ... Martov/Czernin

- Peter Gordon ... Von Kuhlmann

- Godfrey James ... Mdvani/Russian General

- Sara Kestelman ... Kollontai

- Michael Kitchen ... Leon Trotsky

- John Labanowski ... Zhelnik

- Trevor Martin ... Minister

- Stephen Moore ... Anatoly Lunacharsky

- John Normington ... Felix Dzerzhinsky

- Terence Rigby ... Joseph Stalin

- June Watson ... Krupskaya

- Catherine Harding ... Spiridonovna

- Michael Stroud ... An Anarchist

- Louis Haslar ... Old Soldier

- Edwin Brown ... General Hoffman

References

- Bolt, Robert (16 November 1977). "State of Revolution: a play in two acts". Heinemann Educational [for] the National Theatre – via National Library of Australia (new catalog).

- "OBITUARY : Robert Bolt". The Independent. 23 February 1995.

- Nightingale, Benedict (19 June 1977). "Robert Bolt Takes a Detached Look at Lenin & Co" – via NYTimes.com.

- "Production of State of Revolution | Theatricalia". theatricalia.com.