Stallion

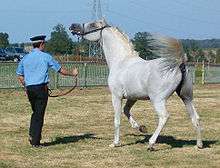

A stallion is a male horse that has not been gelded (castrated). Stallions follow the conformation and phenotype of their breed, but within that standard, the presence of hormones such as testosterone may give stallions a thicker, "cresty" neck, as well as a somewhat more muscular physique as compared to female horses, known as mares, and castrated males, called geldings.

Temperament varies widely based on genetics, and training, but because of their instincts as herd animals, they may be prone to aggressive behavior, particularly toward other stallions, and thus require careful management by knowledgeable handlers. However, with proper training and management, stallions are effective equine athletes at the highest levels of many disciplines, including horse racing, horse shows, and international Olympic competition.

The term "stallion" dates from the era of Henry VII, who passed a number of laws relating to the breeding and export of horses in an attempt to improve the British stock, under which it was forbidden to allow uncastrated male horses to be turned out in fields or on the commons; they had to be "kept within bounds and tied in stalls." (The term "stallion" for an uncastrated male horse dates from this time; stallion = stalled one.)[1] "Stallion" is also used to refer to males of other equids, including zebras and donkeys.

Herd behavior

Contrary to popular myths, many stallions do not live with a harem of mares. Nor, in natural settings, do they fight each other to the death in competition for mares. Being social animals, stallions who are not able to find or win a harem of mares usually band together in stallions-only "bachelor" groups which are composed of stallions of all ages. Even with a band of mares, the stallion is not the leader of a herd but defends and protects the herd from predators and other stallions. The leadership role in a herd is held by a mare, known colloquially as the "lead mare" or "boss mare." The mare determines the movement of the herd as it travels to obtain food, water, and shelter. She also determines the route the herd takes when fleeing from danger. When the herd is in motion, the dominant stallion herds the straggling members closer to the group and acts as a "rear guard" between the herd and a potential source of danger. When the herd is at rest, all members share the responsibility of keeping watch for danger. The stallion is usually on the edge of the group, to defend the herd if needed.

There is usually one dominant mature stallion for every mixed-sex herd of horses. The dominant stallion in the herd will tolerate both sexes of horses while young, but once they become sexually mature, often as yearlings or two-year-olds, the stallion will drive both colts and fillies from the herd. Colts may present competition for the stallion, but studies suggest that driving off young horses of both sexes may also be an instinctive behavior that minimizes the risk of inbreeding within the herd, as most young are the offspring of the dominant stallion in the group. In some cases, a single younger mature male may be tolerated on the fringes of the herd. One theory is that this young male is considered a potential successor, as in time the younger stallion will eventually drive out the older herd stallion.

Fillies usually soon join a different band with a dominant stallion different from the one that sired them. Colts or young stallions without mares of their own usually form small, all-male, "bachelor bands" in the wild. Living in a group gives these stallions the social and protective benefits of living in a herd. A bachelor herd may also contain older stallions who have lost their herd in a challenge.[2]

Other stallions may directly challenge a herd stallion, or may simply attempt to "steal" mares and form a new, smaller herd. In either case, if the two stallions meet, there rarely is a true fight; more often there will be bluffing behavior and the weaker horse will back off. Even if a fight for dominance occurs, rarely do opponents hurt each other in the wild because the weaker combatant has a chance to flee. Fights between stallions in captivity may result in serious injuries; fences and other forms of confinement make it more difficult for the losing animal to safely escape. In the wild, feral stallions have been known to steal or mate with domesticated mares.

Reproductive anatomy

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Equine male reproductive system. |

_(20669607015).jpg)

The stallion's reproductive system is responsible for his sexual behavior and secondary sex characteristics (such as a large crest). The external genitalia comprise:

- the testes, which are suspended horizontally within the scrotum. The testes of an average stallion are ovoids 8 to 12 cm (3.1 to 4.7 in) long, 6 to 7 cm (2.4 to 2.8 in) high by 5 cm (2.0 in) wide;[3]

- the penis, within the prepuce, also known as the "sheath".[4][5] Stallions have a vascular penis. When non-erect, it is quite flaccid and contained within the prepuce (foreskin, or sheath). The retractor penis muscle is relatively underdeveloped. Erection and protrusion take place gradually, by the increasing tumescence of the erectile vascular tissue in the corpus cavernosum penis.[6] When not erect, the penis is housed within the prepuce, 50 cm (20 in) long and 2.5 to 6 cm (0.98 to 2.36 in) in diameter with the distal end 15 to 20 cm (5.9 to 7.9 in). The retractor muscle contracts to retract the penis into the sheath and relaxes to allow the penis to extend from the sheath. When erect, the penis doubles in length and thickness and the glans increases by 3 to 4 times. The urethra opens within the urethral fossa, a small pouch at the distal end of the glans.[7] A structure called the urethral process projects beyond the glans.[8]

The internal genitalia comprise the accessory sex glands, which include the vesicular glands, the prostate gland and the bulbourethral glands.[9] These contribute fluid to the semen at ejaculation, but are not strictly necessary for fertility.[3][10]

Management and handling of domesticated stallions

Domesticated stallions are trained and managed in a variety of ways, depending on the region of the world, the owner's philosophy, and the individual stallion's temperament. In all cases, however, stallions have an inborn tendency to attempt to dominate both other horses and human handlers, and will be affected to some degree by proximity to other horses, especially mares in heat. They must be trained to behave with respect toward humans at all times or else their natural aggressiveness, particularly a tendency to bite, may pose a danger of serious injury.[2]

For this reason, regardless of management style, stallions must be treated as individuals and should only be handled by people who are experienced with horses and thus recognize and correct inappropriate behavior before it becomes a danger.[11] While some breeds are of a more gentle temperament than others, and individual stallions may be well-behaved enough to even be handled by inexperienced people for short periods of time, common sense must always be used. Even the most gentle stallion has natural instincts that may overcome human training. As a general rule, children should not handle stallions, particularly in a breeding environment.

Management of stallions usually follows one of the following models: confinement or "isolation" management, where the stallion is kept alone, or in management systems variously called "natural", "herd", or "pasture" management where the stallion is allowed to be with other horses. In the "harem" model, the stallion is allowed to run loose with mares akin to that of a feral or semi-feral herd. In the "bachelor herd" model, stallions are kept in a male-only group of stallions, or, in some cases, with stallions and geldings. Sometime stallions may periodically be managed in multiple systems, depending on the season of the year.

The advantage of natural types of management is that the stallion is allowed to behave "like a horse" and may exhibit fewer stable vices. In a harem model, the mares may "cycle" or achieve estrus more readily. Proponents of natural management also assert that mares are more likely to "settle" (become pregnant) in a natural herd setting. Some stallion managers keep a stallion with a mare herd year-round, others will only turn a stallion out with mares during the breeding season.[12]

In some places, young domesticated stallions are allowed to live separately in a "bachelor herd" while growing up, kept out of sight, sound or smell of mares. A Swiss study demonstrated that even mature breeding stallions kept well away from other horses could live peacefully together in a herd setting if proper precautions were taken while the initial herd hierarchy was established.[13]

As an example, in the New Forest, England, breeding stallions run out on the open Forest for about two to three months each year with the mares and youngstock. On being taken off the Forest, many of them stay together in bachelor herds for most of the rest of the year.[14][15][16] New Forest stallions, when not in their breeding work, take part on the annual round-ups, working alongside mares and geldings, and compete successfully in many disciplines.[17][18]

There are drawbacks to natural management, however. One is that the breeding date, and hence foaling date, of any given mare will be uncertain. Another problem is the risk of injury to the stallion or mare in the process of natural breeding, or the risk of injury while a hierarchy is established within an all-male herd. Some stallions become very anxious or temperamental in a herd setting and may lose considerable weight, sometimes to the point of a health risk. Some may become highly protective of their mares and thus more aggressive and dangerous to handle. There is also a greater risk that the stallion may escape from a pasture or be stolen. Stallions may break down fences between adjoining fields to fight another stallion or mate with the "wrong" herd of mares, thus putting the pedigree of ensuing foals in question.[19]

The other general method of managing stallions is to confine them individually, sometimes in a small pen or corral with a tall fence, other times in a stable, or, in certain places, in a small field (or paddock) with a strong fence. The advantages to individual confinement include less of a risk of injury to the stallion or to other horses, controlled periods for breeding mares, greater certainty of what mares are bred when, less risk of escape or theft, and ease of access by humans. Some stallions are of such a temperament, or develop vicious behavior due to improper socialization or poor handling, that they must be confined and cannot be kept in a natural setting, either because they behave in a dangerous manner toward other horses, or because they are dangerous to humans when loose.

The drawbacks to confinement vary with the details of the actual method used, but stallions kept out of a herd setting require a careful balance of nutrition and exercise for optimal health and fertility. Lack of exercise can be a serious concern; stallions without sufficient exercise may not only become fat, which may reduce both health and fertility, but also may become aggressive or develop stable vices due to pent-up energy. Some stallions within sight or sound of other horses may become aggressive or noisy, calling or challenging other horses. This sometimes is addressed by keeping stallions in complete isolation from other animals.

However, complete isolation has significant drawbacks; stallions may develop additional behavior problems with aggression due to frustration and pent-up energy. As a general rule, a stallion that has been isolated from the time of weaning or sexual maturity will have a more difficult time adapting to a herd environment than one allowed to live close to other animals. However, as horses are instinctively social creatures, even stallions are believed to benefit from being allowed social interaction with other horses, though proper management and cautions are needed.[13]

Some managers attempt to compromise between the two methods by providing stallions daily turnout by themselves in a field where they can see, smell, and hear other horses. They may be stabled in a barn where there are bars or a grille between stalls where they can look out and see other animals. In some cases, a stallion may be kept with or next to a gelding or a nonhorse companion animal such as a goat, a gelded donkey, a cat, or other creature.

Properly trained stallions can live and work close to mares and to one another. Examples include the Lipizzan stallions of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, Austria, where the entire group of stallions live part-time in a bachelor herd as young colts, then are stabled, train, perform, and travel worldwide as adults with few if any management problems. However, even stallions who are unfamiliar with each other can work safely in reasonable proximity if properly trained; the vast majority of Thoroughbred horses on the racetrack are stallions, as are many equine athletes in other forms of competition. Stallions are often shown together in the same ring at horse shows, particularly in halter classes where their conformation is evaluated. In horse show performance competition, stallions and mares often compete in the same arena with one another, particularly in Western and English "pleasure"-type classes where horses are worked as a group. Overall, stallions can be trained to keep focused on work and may be brilliant performers if properly handled.[20]

A breeding stallion is more apt to present challenging behavior to a human handler than one who has not bred mares, and stallions may be more difficult to handle in spring and summer, during the breeding season, than during the fall and winter. However, some stallions are used for both equestrian uses and for breeding at the same general time of year. Though compromises may need to be made in expectations for both athletic performance and fertility rate, well-trained stallions with good temperaments can be taught that breeding behavior is only allowed in a certain area, or with certain cues, equipment, or with a particular handler.[21][22] However, some stallions lack the temperament to focus on work if also breeding mares in the same general time period, and therefore are taken out of competition either temporarily or permanently to be used for breeding. When permitted by a breed registry, use of artificial insemination is another technique that may reduce behavior problems in stallions.

Cultural views of stallions

Attitudes toward stallions vary between different parts of the world. In some parts of the world, the practice of gelding is not widespread and stallions are common. In other places, most males are gelded and only a few stallions are kept as breeding stock. Horse breeders who produce purebred bloodstock often recommend that no more than the top 10 percent of all males be allowed to reproduce, to continually improve a given breed of horse.

People sometimes have inaccurate beliefs about stallions, both positive and negative. Some beliefs are that stallions are always mean and vicious or uncontrollable; other beliefs are that misbehaving stallions should be allowed to misbehave because they are being "natural", "spirited" or "noble." In some cases, fed by movies and fictional depictions of horses in literature, some people believe a stallion can bond to a single human individual to the exclusion of all others. However, like many other misconceptions, there is only partial truth to these beliefs. Some, though not all stallions can be vicious or hard to handle, occasionally due to genetics, but usually due to improper training. Others are very well-trained and have excellent manners. Misbehaving stallions may look pretty or be exhibiting instinctive behavior, but it can still become dangerous if not corrected. Some stallions do behave better for some people than others, but that can be true of some mares and geldings, as well.

In some parts of Asia and the Middle East, the riding of stallions is widespread, especially among male riders. The gelding of stallions is unusual, viewed culturally as either unnecessary or unnatural. In areas where gelding is not widely practised, stallions are still not needed in numbers as great as mares, and so many will be culled, either sold for horsemeat or simply sold to traders who will take them outside the area. Of those that remain, many will not be used for breeding purposes.

In Europe, Australia, and the Americas, keeping stallions is less common, primarily confined to purebred animals that are usually trained and placed into competition to test their quality as future breeding stock. The majority of stallions are gelded at an early age and then trained for use as everyday working or riding animals.

Geldings

If a stallion is not to be used for breeding, gelding the male horse will allow it to live full-time in a herd with both males and females, reduce aggressive or disruptive behavior, and allow the horse to be around other animals without being seriously distracted.[23] If a horse is not to be used for breeding, it can be gelded prior to reaching sexual maturity. A horse gelded young may grow taller[23] and behave better if this is done.[24] Older stallions that are sterile or otherwise no longer used for breeding may also be gelded and will exhibit calmer behavior, even if previously used for breeding. However, they are more likely to continue stallion-like behaviors than horses gelded at a younger age, especially if they have been used as a breeding stallion. Modern surgical techniques allow castration to be performed on a horse of almost any age with relatively few risks.[25]

In most cases, particularly in modern industrialized cultures, a male horse that is not of sufficient quality to be used for breeding will have a happier life without having to deal with the instinctive, hormone-driven behaviors that come with being left intact. Geldings are safer to handle and present fewer management problems.[24] They are also more widely accepted. Many boarding stables will refuse clients with stallions or charge considerably more money to keep them. Some types of equestrian activity, such as events involving children, or clubs that sponsor purely recreational events such as trail riding, may not permit stallions to participate.

However, just as some pet owners may have conflicting emotions about neutering a male dog or cat, some stallion owners may be unsure about gelding a stallion. One branch of the animal rights community maintains that castration is mutilation and damaging to the animal's psyche.[26]

Ridglings

A ridgling or "rig" is a cryptorchid, a stallion which has one or both testicles undescended. If both testicles are not descended, the horse may appear to be a gelding, but will still behave like a stallion. A gelding that displays stallion-like behaviors is sometimes called a "false rig".[27] In many cases, ridglings are infertile, or have fertility levels that are significantly reduced. The condition is most easily corrected by gelding the horse. A more complex and costly surgical procedure can sometimes correct the condition and restore the animal's fertility, though it is only cost-effective for a horse that has very high potential as a breeding stallion. This surgery generally removes the non-descended testicle, leaving the descended testicle, and creating a horse known as a monorchid stallion. Keeping cryptorchids or surgically-created monorchids as breeding stallions is controversial, as the condition is at least partially genetic and some handlers claim that cryptorchids tend to have greater levels of behavioral problems than normal stallions.[28][29]

See also

References

- Wortley Axe, J (2008), The Horse – Its Treatment in Health And Disease, Hewlett Press, pp. 541–542, ISBN 1-4437-7540-1

- Release, Press (June 29, 2007). "Gender Issues: Training Stallions". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "The Stallion: Breeding Soundness Examination & Reproductive Anatomy". University of Wisconsin-Madison. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- Schumacher, James. "Penis and prepuce." Equine surgery 2 (2006): 540–557.

- Hayes, Captain M. Horace; Knightbridge, Roy (2002). Veterinary Notes for Horse Owners: New Revised Edition of the Standard Work for More Than 100 Years. Simon and Schuster. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-7432-3419-1.

- Sarkar, A. (2003). Sexual Behaviour in Animals. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7141-746-9.

- McKinnon Angus O.; Squires, Edward L.; Vaala, Wendy E.; Varner, Dickson D. (2011). Equine Reproduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-96187-2.

- Equine Research (2005). Horseman's Veterinary Encyclopedia, Revised and Updated. Lyons Press. ISBN 978-0-7627-9451-5.

- Morel, M.C.G.D. (2008). Equine Reproductive Physiology, Breeding and Stud Management. CABI. ISBN 978-1-78064-073-0.

- Parker, Rick. Equine Science (4th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 240. ISBN 111113877X.

- Hatfield, Sandy. "Handle Stallions With Care". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- Strickland, Charlene (July 5, 2007). "Return to Nature With Pasture Breeding". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- Lesté-Lasserre, Christa (June 8, 2010). "Pasturing Stallions Together Can Work, Says Study". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "MINUTES of the Court of Verderers" (PDF). October 19, 2005. p. 3. Retrieved December 26, 2011.(Document refers to the local group-keeping of stallions: 15 stallions on winter grazing at New Park, 20 stallions at Cadland, and to free winter grazing to all stallions passed to run on the Forest, "all those stallions will now remain at our two secure grazing sites at New Park and the Manor of Cadland")

- "MINUTES of the Court of Verderers" (PDF). April 15, 2009. p. 3. Retrieved December 24, 2011.(Document refers to the group-keeping of 22 stallions at Cadland)

- "New Forest Pony Stallions". Nfstallions.info. October 2, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2011.(This site has photographs and video of group-kept stallions)

- "Ellingham show ringside attractions". Ellinghamshow.co.uk. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "Winning Olympia Quadrille". The New Forest Pony. December 18, 2010. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- McDonnell, Sue. "Keeping Horses in Harems". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- Strickland, Charlene. "Males as Athletes". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- Mendell, Chad (2005). "Stallion Handling (AAEP 2005)". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- McDonnell, Sue. "Keeping Stallions Focused". The Horse. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "The Advantages of Spaying and Castrating Horses". Netvet UK. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Hill, Cherry (2008). "Gelding and Aftercare". Cherry Hill. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Cable, Christina S. (April 1, 2001). "Castration in the Horse". The Horse. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Schmid, Mark (February 20, 2010). "What is Castration / Spaying / Neutering?". Organization for Animal Dignity. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- "When is a gelding actually a rig?". Horse & Hound. February 11, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Paulick, Ray (November 5, 2004). "Surgery to Address Roman Ruler's Ridgling Condition". The Horse. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Smith Thomas, Heater (July 1, 2004). "Stallion or Gelding?". The Horse. Retrieved March 3, 2014.