Staffordshire figure

Staffordshire figures are a type of popular pottery figurine made in England from the 18th century onward. Most Staffordshire figures made from 1740 to 1900 were produced by small potteries and makers' marks are generally absent. Most Victorian figures (1837 to 1900) were designed to stand on a shelf or mantlepiece and are therefore only modelled and decorated where visible from the front and sides. These are known as 'flatbacks'.

_MET_DP-1372-070_(cropped).jpg)

Figures were mainly made in Staffordshire but also in other counties and Scotland; all these may loosely be termed "Staffordshire figures". The figures described by the term are normally in earthenware, though early ones may be in stoneware, and the more expensive porcelain figures by the larger potteries in Staffordshire and elsewhere in England are not normally included under the term. These reflected metropolitan and international styles, and were more carefully modelled and painted. For a period at the end of the 18th century the finest Staffordshire figures attempted to compete in this market, but gradually makers abandoned these attempts and settled for a larger mass-market buying cheaper figures.

Of the huge variety of figures produced, the Staffordshire dog figurine was the most ubiquitous, especially as a pair of King Charles Spaniels for a mantelpiece. Once cheap, Staffordshire figures are extensively collected in the English-speaking world, and modern imitations and forgeries abound. The rarest figures, mostly early ones, can sometimes fetch prices into six figures. A pew group of c. 1745 sold for $168,000 at a Christie's auction in 2006,[3] and in 1987 Sotheby's sold one for $179,520.[4]

The figures vary considerably in size: around five to seven inches tall is the most typical for a standing figure, though equestrian figures and bocage groups often reach ten inches. The largest figures, from about 1780 to 1810, can be 20 inches tall, and the smallest as little as 2 inches. They have been keenly collected over the past century, although even the late mass-market figures are now expensive, and there is a considerable literature devoted to them.

Manufacture

Various manufacturing processes were in use at different periods of time,[5] frequently overlapping. What follows are brief summaries of the processes[6] involved.

- Circa 1740–1780 Early figures: rare salt-glazed stoneware with limited range of colours; coloured lead glazes applied to the 'biscuit' earthenware body, then fired[7].

- Circa 1780–1840 Pratt Ware figures, colours applied to the 'biscuit' body, then covered with clear lead glaze, then fired[8].

- Circa 1800–1837 Pre-Victorian Staffordshire figures, clear lead glaze applied to the 'biscuit' body and fired, then colours applied over the lead glaze and fired[9].

- Circa 1837–1900 Victorian Staffordshire figures, blue-tinged lead glaze applied to the 'biscuit' body and fired, then colours applied over the lead glaze and fired, finally gilt applied and fired[10].

Hawk figures, salt-glazed, circa 1750. MET 99567

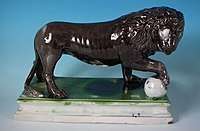

Hawk figures, salt-glazed, circa 1750. MET 99567 Medici lion figure by Ralph Wood, coloured glazes, circa 1780

Medici lion figure by Ralph Wood, coloured glazes, circa 1780

Medici lion, fine painted enamels on lead glaze, circa 1820

Medici lion, fine painted enamels on lead glaze, circa 1820

18th-century types

1740–1760s

Staffordshire figures began to be produced around the 1740s, or perhaps the 1730s. Initially they had little or no painted colour, typically black dots to highlight eyes, buttons, or shoes. Early subjects included genre figures of ladies and gentlemen, musicians, lovers, soldiers and the like. Two elaborate group subjects were the "arbour group", with two lovers seated in front of a bocage of foliage, and the "pew group" of figures sitting on a high-backed bench. The arbour group is a simplification of porcelain groups, whereas the pew group is more original to Staffordshire.[11] Typically it has two or three figures, with a woman in the centre; great attention is paid to details of hair and clothing. The setting is not church, as the usual name suggests, but a comfortable home or inn, where high-backed settles (protecting from draughts) were a common piece of furniture.[12]

The groups are usually in salt-glazed stoneware, but smaller single figures usually in glazed earthenware, which may be agateware, mixing white and brown clay immediately before shaping to give a marbling effect. The pew groups were apparently usually shaped and constructed individually, built up from "slabs" rolled flat,[13] except for the hands and faces,[14] but otherwise moulds were used to form even the early figures.

There are animal figures, with cats rather outnumbering dogs at this period. Some animals are very loosely copying the styles of equivalent animals in Chinese export porcelain. Animals are more likely to be in salt-glazed stoneware, with green, brown and blue glazes the main colours, applied in broad strokes as highlights.

The earliest figures cannot be attributed to specific makers, but by 1750 some figures are given to notable potters, such as Thomas Whieldon, who probably invented tortoiseshell ware in the late 1740s. Others, by his imitators, are called "Whieldon-type"; many were probably made by William Greatbatch, formerly with Whieldon.

.jpg) Pew group, c. 1745, salt-glazed stoneware

Pew group, c. 1745, salt-glazed stoneware.jpg) Arbour group, c. 1750; only the eyes have paint. The bocage behind is built up from moulded sections.

Arbour group, c. 1750; only the eyes have paint. The bocage behind is built up from moulded sections..jpg) The inflammatory High Church Anglican divine Henry Sacheverell (d. 1724), c. 1745, stoneware

The inflammatory High Church Anglican divine Henry Sacheverell (d. 1724), c. 1745, stoneware.jpg) Arbour group, c. 1750; lead-glazed earthenware

Arbour group, c. 1750; lead-glazed earthenware.jpg) Cat, c. 1745, with agateware effects, and underglaze blue highlights

Cat, c. 1745, with agateware effects, and underglaze blue highlights Cat, c. 1750, "Whieldon-type" in tortoiseshell ware

Cat, c. 1750, "Whieldon-type" in tortoiseshell ware.jpg) Oriental lady and her dog, c. 1750, tortoiseshell ware by Thomas Whieldon

Oriental lady and her dog, c. 1750, tortoiseshell ware by Thomas Whieldon.jpg) "Whieldon-type" milkmaid and her cow, with fanciful bocage, c. 1750s

"Whieldon-type" milkmaid and her cow, with fanciful bocage, c. 1750s.jpg) Soldier and man reading (not a pair), "Whieldon-type", c. 1760

Soldier and man reading (not a pair), "Whieldon-type", c. 1760 Pair of water buffalos and Chinese boys, "Whieldon-type", c. 1760

Pair of water buffalos and Chinese boys, "Whieldon-type", c. 1760

1770–1800

.jpg)

From about 1770, as the Staffordshire industry continued to grow, and improve its products, the artistic standards of the best figures improved considerably, though at the loss of most of the folk art charm of the previous period. The subjects became less rustic, and drew closer to those made in porcelain. These included allegorical sets of subjects such as the Four Seasons and personifications of virtues, and portraits of notable figues, often as busts, could be finely modelled. Like other Staffordshire wares, the figures were increasingly reaching the American market, shipped from Liverpool, and the Founding Fathers were well-represented; some of these were also no doubt sold in Britain.

More makers and modellers are identifiable, including three generations of Ralph Woods. Ralph Wood I had modelled for Whieldon, and was a cousin of Enoch Wood, whose father Aaron had also worked for Whieldon. Both families ran large potteries, making a wide range of wares. The Woods were themselves modellers, but other potteries who aimed to compete with porcelain used specialist modellers like John Voyez, who had been fired and then prosecuted by Josiah Wedgwood, and was jailed in 1769.

The figures were now typically painted, either in coloured lead-glazes or in overglaze enamels; this was generally very carefully done, much more so than in the next century, using a wide range of colours. Transfer-printing, which was becoming highly important for tablewares, was not really practical for figures,[15] and hand-painting in overglaze enamels became the norm. The large figures aimed at the top of the market are especially a feature of the period from about 1785 to 1815, but cheaper and cruder figures continued to be produced.

The Demosthenes model shown below first appears about 1785, by Enoch Wood. It is sometimes called Saint Paul Preaching or Eloquence, and possibly was sometimes marketed as such, but the relief scene on the podium strongly suggests it was designed to depict the Greek orator who trained himself by addressing the sea.[16]

As with porcelain figures, the same model might be produced in fully painted and plain versions, and the painting often varies greatly between different examples, especially when moulds were in use for several years. Many model types introduced in this period remained popular until at least the middle of the next century, for example the Parson and Moses type, derived from a print of 1736 by William Hogarth, The Sleeping Congregation.[17]

Couple with birdcage, John Voyez, c. 1765

Couple with birdcage, John Voyez, c. 1765 Woman feeding chickens, c. 1765

Woman feeding chickens, c. 1765 William III as a Roman emperor, Ralph Wood II, 1770s. Lead-glazed earthenware, 14 inches

William III as a Roman emperor, Ralph Wood II, 1770s. Lead-glazed earthenware, 14 inches_(one_of_a_pair)_MET_DP-1372-027.jpg) Chaucer and Isaac Newton, Ralph Wood II, c. 1790. About 12 inches (30 cm) tall

Chaucer and Isaac Newton, Ralph Wood II, c. 1790. About 12 inches (30 cm) tall Large classical figures for the wealthy, Prudence and Fortitude, c. 1790, 20ins tall. Probably Enoch Wood & Caldwell

Large classical figures for the wealthy, Prudence and Fortitude, c. 1790, 20ins tall. Probably Enoch Wood & Caldwell Demosthenes, version c. 1800 of a figure from the 1780s, over 18 inches tall (47.5 cm), by Enoch Wood

Demosthenes, version c. 1800 of a figure from the 1780s, over 18 inches tall (47.5 cm), by Enoch Wood

Social context

.jpg)

In the 19th century, especially after 1820, earthenware figures very largely abandoned attempts to compete with upmarket porcelain figures, and the larger firms pulled out of the earthenware figure market. In fact the taste for figures at the top of the market had greatly reduced even for the porcelain companies. Instead, increasing prosperity opened new popular markets for the figures, and Staffordshire figure manufacturers went downmarket, reducing the complexity of their shapes and painting, and gradually broadening their range of subjects. At the same time Staffordshire transfer-printed tablewares of excellent quality were becoming cheaper, but this market was becoming dominated by the larger potteries, perhaps pushing smaller operations into the figure market.

They were able to greatly increase the volume of figures by appealing to this new and much larger market, and more manufacturers were active in this area. These trends of increasing production, and decreasing quality and prices, continued for most of the century. From the mid-century, or even 1840, all figures were aimed at the low end of the market, and once again few makers are identifiable. Higher quality figures were made in porcelain, and new ceramic materials like Parian ware, as well as some types of stoneware, but in the 19th century "Staffordshire figure" comes to denote specifically the cheaper earthenware types.

Staffordshire figures document, in a unique and tangible manner, a particular aspect of the social history of 19th century England.[18] Oliver describes them as important English folk art, "of the people for the people".[19]

Very similar designs frequently appear in a number of different versions, as makers copied each others' designs, and as numbers of moulds were made for popular figures.

Industrialisation, an exodus from country to town, and population increase proceeded throughout the century.[20] For the first time in modern history, working class people had funds sufficient to buy figures if they so wished; the prices of the cheapest class of figure had dropped considerably. Manufacturers aimed to appeal to public taste, thereby leaving a physical record of the pursuits and interests of the time in a fascinating array of pottery figures.

19th-century types

Rural idylls, farm animals and pets

Figures reminding townspeople of their rural past proved immensely popular, with images of idealised pleasures and pastimes. However, these pastoral images had been more popular in the 18th century, and became less important as the 19th century went on.

"Contest", one of a pair, 1800-1815, pearlware

"Contest", one of a pair, 1800-1815, pearlware- "Perswaition", 1815-25, a misspelling of "Persuasion", but based on a print of 1809, not the Jane Austen novel of 1818.[21]

Bocage group, idyllic rural scene, circa 1820.

Bocage group, idyllic rural scene, circa 1820. The Tithe Pig, 1825-1830, pearlware. Like many images of the clergy, this has an element of satire.

The Tithe Pig, 1825-1830, pearlware. Like many images of the clergy, this has an element of satire. Fantasy depiction of a country cottage, circa 1860.

Fantasy depiction of a country cottage, circa 1860. Small staffordshire pottery figure of a castle 2.6ins tall, circa 1860.

Small staffordshire pottery figure of a castle 2.6ins tall, circa 1860. Small Staffordshire pottery figures of recumbent sheep, 2ins tall, circa 1855.

Small Staffordshire pottery figures of recumbent sheep, 2ins tall, circa 1855.

Domestic pets were another favourite. Queen Victoria's collection of animals and her popularity with the nation resulted in an explosion of cats, spaniels, whippets[22], parrots and others. These were often in pairs facing each other, for the mantelpiece. Much the most popular were pairs of Staffordshire dog figurines, usually with the King Charles spaniel.

Greyhound pen holders, c. 1825-1840

Greyhound pen holders, c. 1825-1840 Pair of Staffordshire cat figures, circa 1920.

Pair of Staffordshire cat figures, circa 1920. Pair of Whippets and Hares figures, circa 1860.

Pair of Whippets and Hares figures, circa 1860. Inkwell, parrot and lamb, circa 1860,

Inkwell, parrot and lamb, circa 1860, Recumbent Staffordshire spaniel figure, circa 1860.

Recumbent Staffordshire spaniel figure, circa 1860. Small staffordshire pottery figure of inkwell 2.1ins tall dogs on cushion, circa 1860

Small staffordshire pottery figure of inkwell 2.1ins tall dogs on cushion, circa 1860

Public life and sensations

Portrait figures of the era[23] depict all the best known personalities of the period and no small number who were briefly newsworthy only to fade from memory. Especially popular were those depicting figures involved in reforms, victories at war, hero's and heroines whose activities impacted directly on working people's lives. Characters from legend and fiction were also popular.

Freed Slave, marking the abolition of Slavery in the British Empire, 1833-34. The open book reads "BLESS GOD / THANK BRITON / ME NO SLAVE".

Freed Slave, marking the abolition of Slavery in the British Empire, 1833-34. The open book reads "BLESS GOD / THANK BRITON / ME NO SLAVE". Queen Victoria riding, c. 1838, at the start of her reign.

Queen Victoria riding, c. 1838, at the start of her reign. Portrait figure of Richard Oastler, effective campaigner for reform of factory conditions. Scroll reads 'WHITE SLAVERY'. Circa 1860.

Portrait figure of Richard Oastler, effective campaigner for reform of factory conditions. Scroll reads 'WHITE SLAVERY'. Circa 1860. Chief of Staff during Crimean War, General James Simpson captured Sebastopol in 1855, then knighted, c. 1855.

Chief of Staff during Crimean War, General James Simpson captured Sebastopol in 1855, then knighted, c. 1855. Sir Robert Peel, popular Prime Minister responsible for establishing organised police forces and Public Health Act of 1848, c. 1856.

Sir Robert Peel, popular Prime Minister responsible for establishing organised police forces and Public Health Act of 1848, c. 1856. Florence Nightingale, here with a wounded officer, demonstrated to Crimean War generals that cleanliness saved thousands of lives. Wrote first Nursing Manual and founded the first Nursing School. Circa 1856.

Florence Nightingale, here with a wounded officer, demonstrated to Crimean War generals that cleanliness saved thousands of lives. Wrote first Nursing Manual and founded the first Nursing School. Circa 1856. Figure labelled 'George Washington', though clearly depicting Benjamin Franklin, c. 1855.

Figure labelled 'George Washington', though clearly depicting Benjamin Franklin, c. 1855. Crimean war figure 'Soldier's Farewell', circa 1853.

Crimean war figure 'Soldier's Farewell', circa 1853. Bust of Mary Queen of Scots, c. 1815, pearlware

Bust of Mary Queen of Scots, c. 1815, pearlware- George Washington bust, Enoch Wood, c. 1818. Finely-modelled busts like this were less common than in the late 18th century.

Other figures celebrated scandals, murders, fashion, sport, and the life-transforming novelties of clean water and railways.

.jpg) The Death of Munrow, a notorious hunting accident in India in 1792, evidently still famous in the 1820s, when this was made.

The Death of Munrow, a notorious hunting accident in India in 1792, evidently still famous in the 1820s, when this was made.- Bull baiting group, 1820-1830

"Polito's Menagerie", a real touring show with "burds (sic) and beasts from all parts of the world", c. 1830.[24]

"Polito's Menagerie", a real touring show with "burds (sic) and beasts from all parts of the world", c. 1830.[24] 'Death of the Lion Queen'. Ellen Bright, trainer, mauled to death in front of a circus audience. Circa 1856.

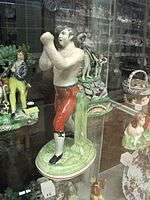

'Death of the Lion Queen'. Ellen Bright, trainer, mauled to death in front of a circus audience. Circa 1856. Leading boxers such as Tom Cribb (d. 1848) were popular subjects

Leading boxers such as Tom Cribb (d. 1848) were popular subjects Group possibly representing Euston Station in London, or generally celebrating the rapid expansion of rail travel, 1850s

Group possibly representing Euston Station in London, or generally celebrating the rapid expansion of rail travel, 1850s Staffordshire 'Stanfield Hall' figure, key location in famously popular murder case. Circa 1860.

Staffordshire 'Stanfield Hall' figure, key location in famously popular murder case. Circa 1860. 'Bloomers', a fashion craze. Circa 1860.

'Bloomers', a fashion craze. Circa 1860. Pair of whippets depicting the sport of hare coursing, c. 1860.

Pair of whippets depicting the sport of hare coursing, c. 1860. Staffordshire spill vase figure celebrating the arrival of clean water following the Great Stink and Public Health Act of 1848.

Staffordshire spill vase figure celebrating the arrival of clean water following the Great Stink and Public Health Act of 1848.

Literature and the theatre

Theatrical,[25] and literary subjects are common.

The actor David Garrick as 'Richard III', c. 1860

The actor David Garrick as 'Richard III', c. 1860- The fictional Uncle Tom and Eva, 1855-1860

From a Welsh legend, the bloodstained hound Gelert, a dead wolf, and the son of Llywelyn the Great, who returns and kills Gelert in error and never smiled again. c. 1860.

From a Welsh legend, the bloodstained hound Gelert, a dead wolf, and the son of Llywelyn the Great, who returns and kills Gelert in error and never smiled again. c. 1860. Ride of Mazeppa, based on Lord Byron's poem of 1818. Depicting the horse as a zebra is a flight of fancy. Spill vase, c. 1860.

Ride of Mazeppa, based on Lord Byron's poem of 1818. Depicting the horse as a zebra is a flight of fancy. Spill vase, c. 1860.

Exotic animals

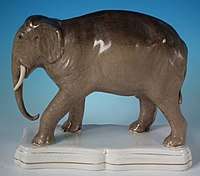

Lions[26], giraffes, tigers, zebras and elephants generated huge excitement, popularised by travelling menageries. Many artists could not resist the temptation to turn horses in zebras.

Leopard, 19th century

Leopard, 19th century Zebra attacked by a snake, 1850-1870

Zebra attacked by a snake, 1850-1870 Giraffe spill vases, 1845-1855

Giraffe spill vases, 1845-1855 Lion, glass eyes, spray decoration, 1890-1900.

Lion, glass eyes, spray decoration, 1890-1900. Large elephant figure, circa 1860.

Large elephant figure, circa 1860. Small staffordshire pottery figures of elephants 2.4ins tall, circa 1860.

Small staffordshire pottery figures of elephants 2.4ins tall, circa 1860. Private collection of zebra figures 1850-1880

Private collection of zebra figures 1850-1880

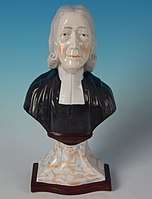

Religion

Religious,[27] and temperance subjects were in great demand[28] Staffordshire pottery owners included many Nonconformists, and John Wesley was the post-biblical religious figure most often depicted, with 18 versions of him and his brother from Victoria's reign alone.[29] A number of bible scenes and figures are depicted, mostly from the Old Testament, but including some New Testament ones, and sets of the Four Evangelists. Images from Catholic iconography, such as the Madonna and Child and some saints were produced, though they are not very common. Some were probably for export, at least to Ireland, and perhaps France.[30] Some 20 Nonconformist preachers, and some other leaders were given figures, with the star preacher Charles Spurgeon the most common contemporary figure, but there is a striking absence of portrait figures of Anglican clergy, though some leading Evangelical Anglican laypeople were depicted, and some Catholic clergy.[31]

Types from the late 18th century satirizing the clergy continued well into the 19th, but new types did not appear; the most popular remained Vicar and Moses, The Tithe Pig and the drunken Parson and Clerk (or Inebriation).[32]

John Wesley, an influential preacher in the Potteries, circa 1840. Derived from an Enoch Wood bust from the previous century.

John Wesley, an influential preacher in the Potteries, circa 1840. Derived from an Enoch Wood bust from the previous century. The charismatic Baptist preacher, Charles Spurgeon, c. 1860.

The charismatic Baptist preacher, Charles Spurgeon, c. 1860. Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, c. 1860.

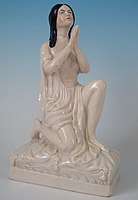

Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, c. 1860. Girl at prayer, circa 1860.

Girl at prayer, circa 1860. Temperance movement figure 'Band of Hope', a society for children who had taken the pledge, circa 1847.[33]

Temperance movement figure 'Band of Hope', a society for children who had taken the pledge, circa 1847.[33]

Notes

- Winterthur Museum, page about their collection

- Briggs, 63-64; "Vicar and Moses".

- A STAFFORDSHIRE CREAMWARE 'PEW GROUP', CIRCA 1745, Lot 500, Sale 1618, "Property From the Collection of Mrs. J. Insley Blair", New York, 21 January 2006.

- "PASSIONATE COLLECTORS SET NEW AUCTION HIGHS", by Rita Reif, 22 January 1987, New York Times

- A Collector's History of English Pottery, Griselda Lewis, Antique Collectors Club, 1999.

- Methods used to apply color to early antique Staffordshire pottery figures, Myrna Schkolne, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lFFjfAWzSoI

- English Earthenware Figures 1740–1840, Pat Halfpenny, 1991

- Pratt Ware 1780–1840, John and Griselda Lewis, 2005

- People, Passions, Pastimes, and Pleasures: Staffordshire Figures 1780–1840, Myrna Schkolne, 2006

- Victorian Staffordshire Figures 1835–1875 Books 1–4, A. & N. Harding, 2000

- Wood, 21–23

- Poole, 56–57 (online)

- Poole, 56–57

- "Pew Group", Fitzwilliam Museum

- Wood, 23

- "What's in a name", www.mystaffordshirefigures.com/blog

- "Vicar and Moses"; [File:The Sleeping Congregation MET DP824961.jpg Example in the Metropolitan]

- Modern Christianity and Cultural Aspirations, 2003, A & C Black, edited by David Bebbington, Timothy Larsen. "By the mid-nineteenth century a new mass-produced type of colourful flatback Staffordshire figure appeared…"

- Staffordshire Pottery: the Tribal Art of England, Anthony Oliver, 1981

- The population of England rose from 8.3 million in 1801, to 16.8 million in 1851 half now living in towns, to 30.5 million in 1901

- "Perswaition", mystaffordshirefigures.com/blog

- A-Z of Staffordshire Dogs, Clive Mason Pope, 1998, Thirty breeds referenced.

- Staffordshire Portrait Figures of the Victorian Age, P. D. Gordon Pugh, 1971

- V&A database

- The Oxford Handbook of the Georgian Theatre 1737-1832, OUP, 2014, edited by Julia Swindells, David Francis Taylor "By the mid-nineteenth century a new mass-produced type of colourful flatback Staffordshire figure appeared…"

- Antiques Trade Gazette, 2004"Combining exotic subject matter with rarity value, figures of the Victorian lion-tamer Isaac Van Amburgh are among the most desirable of all Staffordshire portrait figures."

- Briggs, throughout, 57-63 especially

- Briggs, 75-77; Victorian Staffordshire Pottery Religious Figures, Stephen Duckworth, 2016

- Briggs, 70

- Briggs, 58-63

- Briggs, throughout, especially 56-76

- Briggs, 63-65

- Briggs, 75

References

- Briggs, John, "Nonconformity and the Pottery Industry", in Modern Christianity and Cultural Aspirations, eds. David Bebbington, Timothy Larsen, 2003, A&C Black, ISBN 0826462626, 9780826462626, google books

- Poole, Julia, English Pottery (Fitzwilliam Museum Handbooks), 1995, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521475201

- Wood, Frank L., The World of British Stoneware: Its History, Manufacture and Wares, 2014, Troubador Publishing Ltd, ISBN 178306367X, 9781783063673

- Schkolne, Myrna, Obsession: Collection of Early English Pottery, Vol.1, 2020,

- Schkolne, Myrna, Obsession: Collection of Early English Pottery, Vol.2, 2020,

- Schkolne, Myrna, Obsession: Collection of Early English Pottery, Vol.3, 2020,

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Staffordshire figures. |