St Melangell's Church, Pennant Melangell

St Melangell's Church, Pennant Melangell is a small church located on a minor road which joins the B4391 near the village of Llangynog, Powys, Wales. It houses the restored shrine of Saint Melangell,[1] reputed to be the oldest Romanesque shrine in Great Britain.

| St Melangell's church, Pennant Melangell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Llangynog, Powys SY10 0HQ |

| Country | Wales |

| Denomination | Church in Wales |

| Website | The Shrine Church of Saint Melangell, Pennant Melangell |

| History | |

| Founded | 8th century |

| Founder(s) | Saint Melangell |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Historic |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Llangynog |

| Deanery | Llanfyllin |

| Diocese | St Asaph |

| Province | Church in Wales |

| Clergy | |

| Priest(s) | The Reverend Christine Browne |

History

The church of St Melangell is set in a circular churchyard, possibly once a Bronze Age burial site, ringed by ancient yew trees, which may also predate the Christian era. It sits at the foot of a breast-shaped hill,[2] at the edge of the road on the edge of the Berwyn mountains. Also located at the site is the restored shrine of St Melangell, which is reputedly the oldest Romanesque shrine in Britain, dating from the early 12th century.[3]

The shrine is known for the story of St Melangell,[4] who is said in the Historia Divae Monacellae[5] to have hidden a hare[6] in the folds of her cloak to save it from the hounds of Prince Brochwel of Powys: "the pursuing hounds, presumably aware that Melangell's body radiates sanctity, cower and refuse to go near the animal," Jane Cartwright notes, adding, "the power of her virginity protects the creature, since feminine sanctity and virginity are inextricably linked".[7] Though he encouraged his dogs, they could not be urged forward while the virgin remained at prayer, and when his huntsmen went to blow his horn, it stuck to his lips. So impressed was Brochwel by the beauty and courage of this virginal[8] young girl, who had fled from Ireland to avoid a forced marriage, that he gave her the land in the valley where her church still stands.[9] The hares were locally called "Melangell's lambs".[10] Thus like Oudoceus, and Cybi's goat, Melangell "won territory and rights of sanctuary through such animals." "Until the seventeenth century no one would kill a hare in the parish," Agnes Stonehewer remarked in 1876,[11] "and much later, when one was pursued by dogs, it was firmly believed that if anyone cried 'God and St. Monacella be with thee!' it was sure to escape." The hare is also noted as the animal with local sanctity, that must not be killed in Pennant Melangell, by N. W. Thomas in 1900.[12]

Building

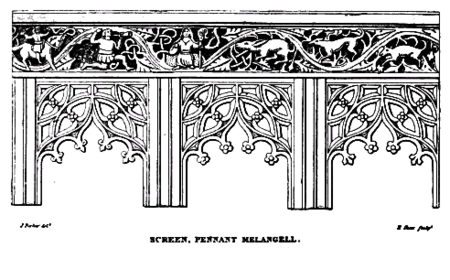

The church consists of a nave and chancel in one, an eastern apse, and at the west end a tower. The building is oriented slightly north of true east. Roofs consist of slates with stone ridge tiles and the base of a cross finial at the east end. Black ceramic ridge tiles adorn the porch.[13] The church contains a fine 15th-century oak rood screen with carvings that tell the story of Melangell and Prince Brochwel:

- "First compartment. Brochwel Yscythrog, Prince of Powys, on horseback; his bridle tied on the mane of the horse; both arms extended; in his right hand a sword which he is brandishing. He wears long hair under a flat cap; a close-fitting coat and girdle, both painted red, and sits in the high saddle of the Middle Ages. He is the most distant figure of the series.

- The second compartment is partly damaged in the branch-work, but the figure is entire. The huntsman, half-kneeling, tries in vain to remove the horn, which he was raising to his lips for the purpose of blowing it. when it remained fast and could not be sounded.

- In the third, St. Melangell, or Monacella, is represented as an abbess; her right hand slightly raised; her left hand grasping a foliated crozier; a veil upon her head. The figure, seated on a red cushion, is larger than that of Brochwel, and smaller than that of the huntsman.

- A hunted hare, crouching or scuttling towards the figure of the Saint. The hare is painted red.

- A greyhound in pursuit; the legs, entangled among the branches of the running border, can hardly be distinguished from them. The dog is painted of a pale colour.

- A nondescript animal, intended, I suppose, for a dog. In this and the 5th compartment the hounds are supposed to be further from the eye than the hare, which is the largest figure in the whole range.

- One tracery panel lies its gouge-work painted red; the gouge-work of the next is blue; that of the next is red; and so on alternately."

The screen itself, on the rood-loft of which the above formed a cornice or frieze, still remains in its position between the chancel and the nave. It comprises four compartments on each side of the doorway, or entrance, which is just double the width of the side divisions; the spandrels are filled with tracery of the same design, and of fourteenth-century character.[14]

There are also two medieval effigies, one of which is thought to represent the saint; a Norman font, a Georgian pulpit, chandelier and commandment board, a series of stone carvings of the hare by the sculptor Meical Watts, and the mysterious Giant’s Rib.[15]

Churchyard

The circular churchyard, possibly once a Bronze Age burial site, is ringed by ancient yew trees, which may also predate the Christian era. It contains the war graves of three British Army soldiers of World War I.[16]

Church services

St Melangell's Church has always been a Pilgrims' Church, attracting visitors come from all over Britain and beyond. Sunday services are held throughout the year at 3.00 p.m., an informal liturgy. On Thursday the Holy Eucharist is at noon throughout the year. There is a tradition of serving tea and cake following the Sunday afternoon service.

Pennant Melangell Church painted in 1795

Pennant Melangell Church painted in 1795- Church tower at Pennant Melangell with the breast-shaped hill in the background

- Grave Apse.

- Valley dawn at Pennant Melangell.

- A corner of St Melangell's shrine, the floor covered with hundreds of prayer cards.

- Shrine of St Melangell.

Footnotes

- Monacella, "little nun" is the Latin form of her name.

- Cheryl Straffon, The Goddess in the Landscape of Wales

- Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust

- Melangell is one of four named saints whose legends are told in W. Jenkyn Thomas, (Juliette Wood, introduction and appendix)The Welsh Fairy Book, (Cardiff, 1995), and William Eliot Griffis, Welsh Fairy Tales, (World Library reprint, 2007) ch. 1 "Welsh rabbit and hunted hares". She was included for the first time in the Oxford Dictionary of Saints in the 1997 edition.

- Huw Price, "A new edition of the Historia Divae Monacellae", Montgomeryshire Collections 82 (1994:23–40).

- Transformation into hares is a feature of Celtic mythology, notably in Welsh mythology where gwiddonod (witches) have this ability.

- Jane Cartwright, "Virginity and chastity tests in medieval Welsh prose", Anke Bernau, Ruth Evans and Sarah Salih, eds. Medieval virginities 2003:56–79, p. 60. "

- The emphasis on virginity in Welsh hagiography is examined by Jane Cartwright, "Dead virgins: feminine sanctity in medieval Wales", Medium Aevum 71 (2002:1–28).

- Ven. Archdeacon Thomas, "Montgomeryshire screens and roodlofts", Archaeologia Cambrensis, The Journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association, Vol. III, Sixth Series, London, 1903, p. 109]

- Griffis, Thomas, Wood.

- Agnes Stonehewer, "The Legend of St. Monacella", a preface to her blank verse "Monacella: a poem" (London: Henry King & Son) 1876.

- Thomas, "Animal Superstitions and Totemism", Folklore 11.3 (September 1900):227–267) p. 240; see also Elissa R. Henken, "The Saint as Secular Ruler: Aspects of Welsh Hagiography", Folklore 98.2 (1987:226–232) p. 229.

- Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust

- Thomas 1903: 112

- Thomas 1903.

- CWGC Cemetery report.

Further reading

- Nancy Edwards, "Celtic Saints and Early Medieval Archaeology," in Local saints and local churches in the early medieval West (Oxford University Press, 2002), pp. 234ff. online.