St Mary's Church, Chastleton

The Church of St Mary the Virgin is the Church of England parish church of Chastleton, Oxfordshire, England. It is a parish church in the parish of Little Compton, along with those of Cornwell, Daylesford and Little Rollright. The parish is part of the Team Benefice of Chipping Norton, along with the parishes of Chipping Norton with Over Norton, Churchill and Kingham.[1] The Benefice of Chipping Norton is part of the Diocese of Oxford.[2]

| St Mary the Virgin, Chastleton | |

|---|---|

St Mary's seen from the west from the grounds of Chastleton House | |

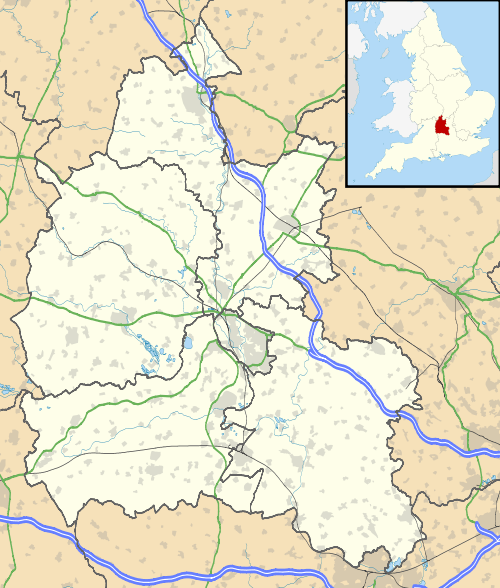

St Mary the Virgin, Chastleton Location in Oxfordshire | |

| OS grid reference | SP24862906 |

| Location | Chastleton, Oxfordhire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | Around the Benefice |

| History | |

| Dedication | St Mary the Virgin |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* listed |

| Designated | 27 August 1957 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Cotswold stone |

| Administration | |

| Deanery | Chipping Norton |

| Archdeaconry | Oxford |

| Diocese | Oxford |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Clergy | |

| Vicar(s) | Rev Canon Stephen Weston |

The church was built in about AD 1100 and enlarged in 1320.[3] The present bell-tower was added in 1689.[4] The church was restored in 1878–80 to designs by CE Powell[4] and is a Grade II* listed building.[5]

History

St Mary's parish church was built in about AD 1100. All that remains of the original Norman church are a door in the north wall, the arched pillars and possibly the baptismal font.

In about 1320 the chancel was built, part of the north wall was widened and the south aisle was added to form chantry chapels.[3]

South aisle chapel

The chapel received its charter as a chantry in 1336. Robert Trillowe, who lived on the site of Chastleton House, was probably the patron. The floor has medieval glazed fired floor-tiles which almost certainly date from the 14th century.

The east window depicts the four Evangelists. The South window shows scenes from the childhood of Jesus.

The panelling on the east wall is 17th century, as are the pews. The ceiling is Victorian and bears the coats of arms of five successive families of the Manor of Chastleton: Trillowe, Catesby, Jones, Whitmore and Whitmore-Jones. In a vault below the chapel lie the remains of some of these families.

The altar was designed in 1993 by Mr Poole from the nearby village of Oddington, Gloucestershire and matches the adjoining 14th century pillars.[3]

Chancel

The carved woodwork behind the altar may well be the remains of the rood screen which once stood above the chancel arch. Below the chancel were tombs of some of the Jones family, was well as those of some of the former parish rectors. Horatio Westmacott, rector in the 1880s was the third son of the famous Victorian sculptor Sir Richard Westmacott.

On the floor of the south aisle near the lectern are two brasses. One commemorates the grandmother of Robert Catesby, Katherine Throckmorton, who died in 1592. The other commemorates Edmund Ansley, who died in 1613.[4][5]

Pulpit and pews

The pulpit is Jacobean, possibly by the same craftsman who made much of the panelling in Chastleton House. It is marked with the date 1623.[5] Originally sited on the other side of the chancel arch, it was built as a triple-decker, with integral reading desk and clerk's desk.

The pews in the nave and chancel are Victorian. These replaced Jacobean oak benches and pews with high backs, of which three remain in the South aisle chapel.

North aisle and organ

The organ now hides a stone piscina,[5] which is the only sign of a former chantry chapel. J. W. Walker & Sons Ltd built and installed the present organ in 1937. For the 49 years before 1937 the organist was one Walter Newman. In the Middle Ages the church had a west gallery which would have been used by a West Gallery band.

Wall paintings

On the north wall are important examples of 17th and 18th century wall paintings which may formerly have covered the entire wall. Most of the paintings, which were uncovered in the 1930s, are post-mediaeval[5] and depict The Ten Commandments and/or The Lord's Prayer, A further painting on the south wall, depicting The Last Judgement, was uncovered in 1878 but was covered over again soon after.

West end

The west window is 14th century with glass dating from the 1900s. The gallery, accessed by a stairway, the small window for which remains, was removed in 1878. The font is thought to be 13th century or possibly earlier.

Bells

The tower has a ring of six bells. Richard Keene of Woodstock cast the third bell in 1696.[6] There were three bells until 1726, when the ring was increased to four. Henry III Bagley, who had a bell-foundry at Witney, cast the fourth and fifth bells in 1731.[6] Matthew III Bagley of Chacombe, Northamptonshire cast the second bell in 1762.[6] John Rudhall of Gloucester cast the treble bell in 1811[6] and the tenor bell in 1825,[6] increasing the ring to six.

Henry Bond of Burford refurbished the bells in 1900. In 1993 nearly £40,000 was raised for the bells to be re-tuned and re-hung. The Whitechapel Bell Foundry re-tuned them and Whites of Appleton re-hung them in a new steel frame.

The bells are rung regularly by a team from the village, supported by ringers from the nearby parish church at Salford. The bell ringing chamber is on the first floor of the tower which is entered by the south door in the base of the tower. The ringing chamber is accessed by a short flight of ladder type steps with a trap-door at the top, which is closed during ringing.[7]

Churchyard

On the north side of the church yard, adjoining Chastleton House and near the north door of the church, lies the tomb of Sir Richard Westmacott (1775–1855), perhaps the greatest monumental sculptor of the Victorian era.

Other notable burials in the churchyard include those of Alan Clutton-Brock of Chastleton House, Newbury Racecourse manager Geoffrey Freer and CLT Walwyn, father of racehorse trainer Peter Walwyn.

Families associated with the church

Trillowe

The Trillowe family lived on the site of Chastleton House from about 1302. There are records for three family members: John 1302; Robert, patron of the Chantry 1336; and another John 1360. His great-granddaughter Phillippa Bishopsden married William Catesby in the 15th Century.

Catesby

The son of William (husband of Phillippa) was William Catesby Minister to Richard III. The family line continued through George, Richard and two more Williams. The latter William married Anne Throckmorton of Courton. Their son Robert Catesby, the Gunpowder Plot conspirator, lived at Chastleton in 1601, although his son, Robert Catesby Junior, was christened at the church on 11 November 1595.[8] In 1602, after a heavy fine imposed for his involvement in the Essex Rebellion, Catesby was forced to sell Chastleton House to Walter Jones.

Throckmorton

In 1555 Anthony Throckmorton married Katherine, widow of William Catesby. Their nine children were John, Thomas, George, Robert, Mary, Katherine, Elizabeth, Anne and Margaret.

Ansley

Edmund Ansley married Margaret Throckmorton (see above). The Ansley family lived at Brookend, having taken it over from Eynsham Abbey at the Dissolution of the monasteries. Edmund died in 1613 and is buried in the chancel.

Greenwood

In about 1588 the Patronage of the Living of Chastleton passed to the Greenwood family, through George Greenwood's great-uncle Christopher Mychell, who was rector. The family retained the patronage until 1784. Greenwood's house was opposite the church, in what is known as The Park, but was destroyed in the 19th century. In 1608 George married Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Walter Jones.

Jones

Born in Witney in 1550, Walter Jones was the son of a wool merchant and bought Chastleton House in 1602. He may not have taken up residence until 1605. Jones married Elinor Pope, who was a maid of honour to Elizabeth I. Jones began building the present Chastleton House in 1603 and had largely completed it by 1614. He died in 1632 and was buried in the chancel, although his tombstone is no longer visible.

The line of succession for Chastleton ran from Walter to his eldest son Henry (died 1656), his son Arthur (died 1687), his son Henry (died 1688), his son Walter (died 1704), his wife Anne (died 1739), their son Henry (died 1761), his son John (died 1813), his brother Arthur (died 1828) and his cousin John Henry Whitmore.

In the church are wall-mounted monuments to members of the Jones family. Most notable are those to Sarah Jones (died 1687), with festoons and weeping putti and to Anne Jones, who died in 1708.[4][5]

Whitmore Jones

John Henry was required to change his name to Whitmore Jones to inherit the house. Of his four sons, who all remained unmarried, the last died in 1874 and the house passed to the eldest of six daughters, Mary. In 1900 she gave the house to her nephew Thomas Harris, who also changed his name to Whitmore Jones. He married his cousin Irene Dickins, who was the youngest daughter of the third daughter of John Whitmore. Mary died in 1915 and Thomas in 1917.

Irene moved into Chastleton House, from Dover House in the village, in 1933, when the Richardson family relinquished a 37-year tenancy.

Clutton-Brock

In 1937 Alan Clutton-Brock came to join Irene Whitmore Jones at Chastelton House. Soon afterwards he married Barbara Foy-Mitchell and the couple moved away. But when Irene died in 1955, the Foy Clutton-Brocks moved back to the house. Alan, who was a fellow of Kings College, Cambridge died in 1976, but Barbara remained until 1992, when the house was sold to the National Trust.

Richardson

Mr and Mrs CT Richardson were tenants at Chastleton House between 1896 and 1933 and made many important restorations to the layout of the gardens.

References

- Archbishops' Council (2015). "Benefice of Chipping Norton". A Church Near You. Church of England. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Archbishops' Council (2015). "St Mary the Virgin, Chastleton". A Church Near You. Church of England. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Yeomans 1998

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 531.

- Historic England. "Church of St Mary (Grade II*) (1183347)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Davies, Peter (12 December 2006). "Chastleton S Mary V". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- "St. Mary the Virgin, Chastleton, Oxon". Oxford Diocesan Guild of Church Bell Ringers. 19 October 2002. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- "Papers, photographs, maps and drawings relating to Robert Catesby and the Gunpowder Plot". Houses of Parliament. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

Bibliography

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 531. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yeomans, Gwen (1998). Chastleton Church, Oxfordshire. Chastleton: Parish of Saint Mary the Virgin, Chastleton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) for which the sources are:

- Dickins, Margaret (1938). A History of Chastleton. Banbury: Banbury Guardian.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambert, Stephen (n.d.). Chastleton Church History.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duncan Gordon Colebrook – Administrator of Chastleton House

- Stephen Freer – local historian

- Christopher Westmacott

- The Post Office

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Mary the Virgin Church, Chastleton. |