Sports before 1001

This article presents a chronology of sporting development and events from time immemorial until the end of the 10th century CE. The major sporting event of the ancient Greek and Roman periods was the original Olympic Games, which were held every four years at Olympia for over a thousand years. Gladiatorial contests and chariot racing were massively popular. Some modern sports such as archery, athletics, boxing, football, horse racing and wrestling can directly trace their origins back to this period while later sports like cricket and golf trace their evolution from basic activities such as hitting a stone with a stick.

Events of years in sports |

| Other years |

| before 1001 | 1001 to 1600 | 1601 to 1700 | 1701 to 1725 |

Ball and stick games

There are many modern games which call upon the basic action of hitting a ball with some kind of club or stick. These include baseball, cricket, croquet, golf, all forms of hockey, rounders and all forms of tennis. It can be argued that these sports share a common origin which dates back to time immemorial and, as such, can never be found.[1]

Boxing

Events

- ~3000 BCE — fist fighting is depicted in Sumerian relief carvings from the 3rd millennium BCE.[2]

- ~1500 BCE — the earliest evidence for fist fighting with gloves or other forms of hand protection, such as "cestae", is found on a carved vase from Minoan Crete.[2]

- ~1350 BCE — an ancient Egyptian relief from the 2nd millennium BCE depicts both fist-fighters and spectators.[2]

- ~675 BCE — Homer's Iliad (Book XXIII) contains the first detailed account of a boxing contest.[3]

- ~400 BCE — in ancient Greece, a form of cestae called meilichae (μειλίχαι) were in use; they were gloves consisting of strips of raw hide tied under the palm, leaving the fingers bare.[4]

- ~100 BCE — in ancient Rome, boxing was primarily a gladiatorial contest; gladiators wore lead cestae over their knuckles and heavy leather straps on their forearms for protection against blows.[4]

- ~400 CE — boxing apparently went into centuries-long decline after the rise of Christianity and the decline of the Roman Empire.[2]

Chariot racing

- Chariot racing was one of the most popular ancient Greek, Roman and Byzantine sports, despite being dangerous to both driver and horse as they frequently suffered serious injury and even death. In the Roman Empire, it was a major industry.[5]

- 648 BCE — chariot and mounted horse racing were events in the ancient Greek Olympics by this time and featured in the other Panhellenic Games.[6]

Football

Events

- 4th century BCE — the Greek playwright Antiphanes mentioned a team game called "ἐπίσκυρος" (Episkyros) which appears to have resembled rugby football.[7] Episkyros is recognised as an early form of football by FIFA.[8]

- 2nd century BCE — a Chinese game called Cuju (蹴鞠), Tsu' Chu, or Zuqiu (足球) has been recognised by FIFA as the first version of football with regular rules.[9]

- 2nd century BCE — the Roman game harpastum is believed to have been adapted from Episkyros.[10][11]

- 1st century BCE — Cicero (106–43 BCE) described the case of a man who was killed whilst having a shave when a ball was kicked into a barber's shop.[12]

- 644 CE — first evidence that the Japanese ball game of Kemari was being played in Kyoto; it is believed to have been influenced by Chinese Cuju.[13][14]

- 9th century — early reference to a ball game played by boys in Great Britain.[15]

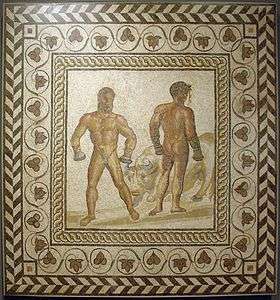

Gladiatorial combat

- the origin of gladiatorial combat is uncertain but possibly began during the Punic Wars of the 3rd century BCE.[16]

- it reached a peak of popularity through a 300-year period from the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE.[17]

- it became an essential feature of politics and social life during much of the Roman Empire period until the 5th century.[18]

Horse racing

Events

- Horse racing has been practised in civilisations across the world since ancient times and archaeological records indicate that it was popular in ancient Greece, Assyria, Babylonia and Egypt.[19] It also figures in myth and legend, such as the contest between the steeds of the god Odin and the giant Hrungnir in Norse mythology.[19]

- 648 BCE — chariot and mounted horse racing were events in the ancient Greek Olympics by this time and featured in the other Panhellenic Games.[6]

- in the Roman Empire, chariot and mounted horse racing were major industries.[5]

Olympic Games

Events

- 776 BCE — the original Ancient Olympic Games were first organised, traditionally in 776 BCE, as a panhellenic religious festival for Zeus. The festival was held four-yearly and this time span was called an Olympiad. Sporting events are believed to have been added to the festivities at a later date. They included footraces, javelin contests and wrestling matches.[21]

- 664 BCE, 660 BCE and 656 BCE — Chionis of Sparta was an outstanding athlete in jumping events.[22]

- 6th century BCE — Milo of Croton victorious in six Olympic Games.[23][24]

- 488 BCE, 484 BCE and 480 BCE — Astylos of Croton was an outstanding athlete in running events.[25]

- 396 BCE and 392 BCE — Cynisca, a Spartan princess, was the first woman to win an event at the Ancient Olympic Games, although she was not allowed to enter the stadium. She owned a successful four-horse chariot racing team that won at successive Olympics.[26]

- 2nd century BCE — the Olympics continued to be celebrated when Greece came under Roman rule.[21]

- 393 CE — Emperor Theodosius I outlawed the Olympics as part of the campaign to impose Christianity as the state religion of Rome.[21]

Polo

Events

- ~600 BCE — Polo originated in Ancient Persia; its invention is dated variously from the 6th century BCE to the 1st century CE.[27][28][29][30]

References

- Major, John (2007). More Than A Game. London: HarperCollins. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-00-718364-7.

- Michael Poliakoff. "Encyclopædia Britannica entry for Boxing". Britannica.com. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- "Iliad, book 23, line 624". Harvard University Press. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Horse racing in Rome". Forequestrians.com. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- "Ancient Greek Olympic Horse Racing". Hellenism.com. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- Nigel Wilson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece, Routledge, 2005, p. 310.

- FIFA.com (8 March 2013). "A gripping Greek derby". FIFA.

- FIFA.com. "History of Football - The Origins - FIFA.com".

- ἐπίσκυρος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007 Edition: "In ancient Greece a game with elements of football, episkuros, or harpaston, was played, and it had migrated to Rome as harpastum by the 2nd century BCE".

- E. Norman Gardiner: "Athletics in the Ancient World", Courier Dover Publications, 2002, ISBN 0-486-42486-3, p. 229.

- Allen Guttmann, Lee Austin Thompson (2001). Japanese sports: a history. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9780824824648. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- Witzig, Richard (2006). The Global Art of Soccer. CusiBoy Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 9780977668809. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- Historia Brittonum at the Medieval Sourcebook.

- Welch, Katherine E. (2007). The Roman Amphitheatre: From Its Origins to the Colosseum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 0-521-80944-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mouritsen, Henrik (2001). Plebs and Politics in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-521-79100-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kyle, Donald G. (2007). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 287. ISBN 0-631-22970-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Earliest record of horse racing". Libraryindex.com. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- Formenti, Federico; Minett, Alberto E. "Human locomotion on ice". Journal of Experimental Biology. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "History". Olympic Games. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- "Chronicle". Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- Poliakoff, Michael B. (1987). Combat Sports in the Ancient World. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 117–119, 182–183. ISBN 0-300-03768-6. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- Harris, H.A. (1964). Greek Athletes and Athletics. London: Hutchinson & Co. pp. 110–113. ISBN 0-313-20754-2.

- Siculus, Diodorus, Historical Library, University of Chicago, 11.1.2.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 3.8.1–3.

- "The History of Polo". Polomuseum.com. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "The origins and history of Polo". Historic-uk.com. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Polo". britannica.com. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- R. G. Goel, Veena Goel, Encyclopaedia of sports and games, Published by Vikas Pub. House, 1988, excerpt from page 318: Persian Polo.