Speed (1994 film)

Speed is a 1994 American action-thriller film directed by Jan de Bont, in his feature film directorial debut. The film stars Keanu Reeves, Dennis Hopper, Sandra Bullock, Joe Morton, and Jeff Daniels. It is about a bus that is rigged by a mad bomber: the bus bomb will arm itself once the bus reaches 50 miles per hour and it will explode if the bus subsequently drops below 50 miles per hour.

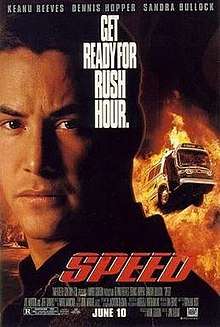

| Speed | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jan de Bont |

| Produced by | Mark Gordon |

| Written by | Graham Yost |

| Based on | Characters by Graham Yost |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Mark Mancina |

| Cinematography | Andrzej Bartkowiak |

| Edited by | John Wright |

Production company | Mark Gordon Productions |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[1][2][3] |

| Box office | $350.4 million[1] |

Released on June 10, 1994, it became critically and commercially successful, grossing $350.4 million on a $30 million budget and winning two Academy Awards, for Best Sound Effects Editing and Best Sound, at the 67th Academy Awards in 1995.

A critically panned sequel, Speed 2: Cruise Control, was released on June 13, 1997.

Plot

LAPD SWAT bomb defusal unit officers Jack Traven and Harry Temple thwart an attempt to hold an elevator full of people for a $3 million ransom by an extortionist bomber, who is later identified as Howard Payne. As they corner Payne, he holds Harry hostage. Jack intentionally shoots Harry in the leg, forcing the bomber to release him. Payne flees and sets off the bomb, seemingly dying in the process. Jack and Harry are praised by Lieutenant "Mac" McMahon and awarded medals for their heroism and Harry is promoted to Detective. However, Payne has somehow survived the incident, and is watching the ceremony from elsewhere.

The next morning, Jack witnesses a mass transit bus explode, killing its driver. Payne contacts Jack on a nearby payphone, explaining that a similar bomb is rigged on another bus. The bomb will activate itself once the bus reaches 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) and detonate if it drops below 50 miles per hour. The bomber demands a larger ransom of $3.7 million and threatens to detonate the bus if the passengers are offloaded. Jack races through freeway traffic and boards the bus, but the bomb is already armed. He explains the situation to Sam Silver, the bus driver. A small-time criminal on the bus, fearing that Jack is about to arrest him, wildly discharges his gun, accidentally wounding Sam. Another passenger, Annie Porter, begins to drive the bus, and when she tries to slow down so Sam can get help, Jack is forced to reveal the bus is rigged to blow if it slows down, to the passengers' shock and horror. Jack examines the bomb under the bus and phones Harry, who uses clues to identify the bomber.

After a harrowing adventure through city traffic, the police clear a route for the bus to an unopened freeway. Mac demands that they offload the passengers onto a flatbed trailer, but Jack warns about Payne's plot. Payne, witnessing the events on TV, calls Jack, reiterates his instructions that no one leaves the bus or he'll detonate the main bomb, but is convinced to allow the officers to offload the injured Sam for medical attention as a show of good will. However, he then detonates a smaller bomb, which kills Helen, another passenger who attempts to get off, causing her to be pulled under the bus and run over, after witnessing it on the live news feed of the event.

When Jack learns that part of the elevated freeway ahead is incomplete, he persuades Annie to accelerate the bus to jump over it, which narrowly succeeds. He directs her to the nearby airport to drive on the unobstructed runways. Meanwhile, Harry identifies Payne's name, his former role as a retired Atlanta police bomb squad officer, and his local Los Angeles address. Harry leads a SWAT team to Payne's home, but the property has been rigged with explosives which detonate, killing Harry and his crew.

In a last-ditch attempt to defuse the bomb, Jack goes under the bus on a towed sled, and he accidentally punctures the fuel tank when the sled breaks from its tow line. Once brought back aboard by the passengers, Jack learns that Harry has been killed and that Payne has been watching the passengers on the bus with a hidden surveillance camera. Mac has a local news crew record the transmission and rebroadcasts it in a loop to fool Payne, while the passengers are offloaded onto an airport bus. Jack and Annie escape the bus from a floor access panel. The empty bus explodes as it collides with a Boeing 707 cargo plane.

Jack and Mac go to Pershing Square to drop the ransom into a trash can. Realizing that he has been fooled, no one died in the bus explosion, and LAPD are waiting to arrest him when he comes for the ransom, Payne poses as a police officer, kidnaps Annie, and recovers the discarded ransom. Jack follows Payne into the Metro Red Line subway, where Annie is fitted with a vest covered with explosives rigged to a pressure-release detonator. Payne hijacks a subway train, handcuffs Annie to a pole, and sets the train in motion while Jack pursues them. After killing the train driver, Payne attempts a bribe with the ransom money, but is enraged when a dye pack in the money bag explodes on him, tainting the cash, and sending him into a crazed frenzy. He and Jack battle on the roof of the train, until Payne is decapitated by a subway tunnel light signal, ending his threat for good.

Jack deactivates the explosive vest from Annie, but cannot free Annie from the pole as she is still handcuffed and Payne had the key. Unable to stop the train, Jack instead cranks it to maximum speed, causing it to plow through a construction site and burst onto Hollywood Boulevard before coming to a stop and eventually freeing Annie. Out of the train, Jack and Annie share a kiss, while a crowd looks on in amusement.

Cast

- Keanu Reeves as Officer Jack Traven

- Dennis Hopper as Howard Payne

- Sandra Bullock as Annie Porter

- Joe Morton as Lieutenant Herb "Mac" McMahon

- Jeff Daniels as Detective Harry Temple

- Alan Ruck as Doug Stephens

- Carlos Carrasco as Ortiz

- Glenn Plummer as Maurice

- Richard Lineback as Sergeant Norwood

- Beth Grant as Helen

- Hawthorne James as Sam Silver

- Richard Schiff as Train Driver

- John Capodice as Bob

Production

Writing

Screenwriter Graham Yost was told by his father, Canadian television host Elwy Yost, about a 1985 film called Runaway Train starring Jon Voight, about a train that speeds out of control. The film was based on a 1963 concept by Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa. Elwy mistakenly believed that the train's situation was due to a bomb on board. Such a theme had in fact been used in a 1975 Japanese film, The Bullet Train. After seeing the Voight film, Graham decided that it would have been better if there had been a bomb on board a bus with the bus being forced to travel at 20 mph to prevent an actual explosion. A friend suggested that this be increased to 50 mph.[4] The film's end was inspired by the end of the 1976 film Silver Streak. Yost had initially named the film Minimum Speed reflecting on the plot element of the bus unable to drop below a speed. He realized that using "minimum" would immediately apply a negative connotation to the title, and simply renamed it to Speed.[5]

Yost's initial script would have the film completely occur on the bus; there was no initial elevator scene, the bus would have driven around Dodger Stadium due to the ability to drive around in circles, and would have culminated with the bus running into the Hollywood Sign and destroying it.[5] Upon finishing the script, Yost took his idea to Paramount Pictures, which expressed interest in green-lighting the film and chose John McTiernan due to his blockbuster films Predator, Die Hard, and The Hunt for Red October. However, McTiernan eventually declined to do so, feeling the script was too much of a Die Hard retread, and suggested Jan De Bont, who agreed to direct because he had the experience of being the photography director for action movies, including McTiernan's Die Hard and The Hunt for Red October. Despite a promising script, Paramount passed on the project, feeling audiences would not want to see a movie which takes place for two hours on a bus, so De Bont and Yost then took the project to 20th Century Fox which also distributed Die Hard.[6] Fox agreed to green-light the project on the condition there were action sequences in the film other than the bus. De Bont then suggested starting the film off with the bomb on an elevator in an office building, as he had an experience of being trapped in an elevator while working on Die Hard.[6] Yost used the opening elevator scene to establish Traven as being clever enough to overcome the villain, comparable to Perseus tricking Medusa into looking at her own reflection.[5] Yost then decided to conclude the film on a subway train to have a final plot twist not involving the action on the bus. Fox then immediately approved the project.[6][5]

In preparing the shooting script, one unnamed author had revised Yost's script in a manner that Yost had called "terrible".[5] Yost spent three days "reconfiguring" this draft.[5] Paul Attanasio was also brought in as a script doctor.[7] Jan de Bont brought in Joss Whedon a week before principal photography started to work on the script.[8] According to Yost: "Joss Whedon wrote 98.9 percent of the dialogue. We were very much in sync, it's just that I didn't write the dialogue as well as he did."[6] One of Whedon's contributions was reworking Traven's character once Keanu Reeves was cast. Reeves did not like how the Jack Traven character came across in Yost's original screenplay. He felt that there were "situations set up for one-liners and I felt it was forced—Die Hard mixed with some kind of screwball comedy."[9] With Reeves' input, Whedon changed Traven from being "a maverick hotshot" to "the polite guy trying not to get anybody killed,"[8] and removed the character's glib dialogue and made him more earnest.[9]

Yost also gave Whedon credit for the "Pop quiz, hotshot" line.[5] Another of Whedon's contributions was changing the character of Doug Stephens (Alan Ruck) from a lawyer ("a bad guy and he died", according to the writer) to a tourist, "just a nice, totally out-of-his-depth guy".[8] Whedon worked predominantly on the dialogue, but also created a few significant plot points, like the killing of Harry Temple.[8] Yost had originally planned for Temple to be the villain of the story, as he felt that having an off-screen antagonist would not be interesting. However, Yost recognized that there was a lot of work in the script to establish Temple as this villain. When Dennis Hopper was cast as Howard Payne, Yost recognized that Hopper's Payne readily worked as a villain, allowing them to rewrite Temple to be non-complicit in the bomb situation.[5]

Casting

Stephen Baldwin, the first choice for the role of Jack Traven, declined the offer because he felt the character (as written in the earlier version of the script) was too much like the John McClane character from Die Hard.[9] According to Yost, they had also considered Tom Cruise, Tom Hanks, Wesley Snipes and Woody Harrelson.[5] Director Jan de Bont ultimately cast Keanu Reeves as Jack Traven after seeing him in Point Break. He felt that the actor was "vulnerable on the screen. He's not threatening to men because he's not that bulky, and he looks great to women".[9] Reeves had dealt with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) before on Point Break, and learned about their concern for human life, which he incorporated into Traven.[9] The director did not want Traven to have long hair and wanted the character "to look strong and in control of himself".[9] To that end, Reeves shaved his head almost completely. The director remembers, "everyone at the studio was scared shitless when they first saw it. There was only like a millimeter. What you see in the movie is actually grown in".[9] Reeves also spent two months at Gold's Gym in Los Angeles to get in shape for the role.[9]

For the character of Annie, Yost said that they initially wrote the character as African American and as a paramedic as to justify how she would be able to handle driving a speeding bus through traffic. The role was offered to Halle Berry but she declined the part.[5] Later, the character had then been changed to a driver's education teacher, and made the character more of a comic-relief sidekick to Jack, with Ellen DeGeneres in mind for the part.[10] Instead, Annie became both Jack's sidekick and later love interest, leading to the casting of Sandra Bullock. Sandra Bullock came to read for Speed with Reeves to make sure there was the right chemistry between the two actors. She recalls that they had to do "all these really physical scenes together, rolling around on the floor and stuff."[11]

Filming

Principal photography began on September 7, 1993, and completed on December 23, 1993, in Los Angeles. De Bont used an 80-foot model of a 50-story elevator shaft for the opening sequence.[12] While Speed was in production, actor and Reeves's close friend River Phoenix died.[9] Immediately after Phoenix died, de Bont changed the shooting schedule to work around Reeves and decided to give him scenes that were easier to do. "It got to him emotionally. He became very quiet, and it took him quite a while to work it out by himself and calm down. It scared the hell out of him", de Bont recalls.[9] Initially, Reeves was nervous about the film's many action sequences but as the shooting progressed he became more involved. He wanted to do the stunt in which Traven jumps from a Jaguar onto the bus himself, and rehearsed it in secret after de Bont disapproved. On the day of the sequence, Reeves did the stunt himself, terrifying de Bont in the process.

Eleven GM New Look buses and three Grumman 870 buses[13] were used in the film's production. Two of them were blown up, one was used for the high-speed scenes, one had the front cut off for inside shots, and one was used solely for the "under bus" shots. Another bus was used for the bus jump scene, which was done in one take.[14]

.jpg)

Many of the film's freeway scenes were filmed on California's Interstate 105 and Interstate 110 at the stack interchange known today as the Judge Harry Pregerson Interchange, which was not officially open at the time of filming. While scouting this location, De Bont noticed big sections of road missing and told screenwriter Graham Yost to add the bus jump over the unfinished freeway to the script.[12] In the scene in which the bus must jump across a gap in an uncompleted elevated freeway-to-freeway ramp while still under construction, a ramp was used to give the bus the necessary lift off so that it could jump the full fifty feet. The bus used in the jump was empty except for the driver, who wore a shock-absorbing harness that suspended him mid-air above the seat, so he could handle the jolt on landing, and avoid spinal injury (as was the case for many stuntmen in previous years that were handling similar stunts). The highway section the bus jumped over is the directional ramp from I-105 WB to I-110 NB (not the HOV ramp from I-110 SB to I-105 WB as commonly believed),[15] and as the flyover was already constructed, a gap was added in the editing process using computer-generated imagery.[14] A 2009 episode of Mythbusters attempted to recreate the bus jump as proposed, including the various tricks that they knew were used by the filmmakers such as the ramp, and proved that the jump, as in the film, would never have been possible.[16]

On a commentary track on the region 1 DVD, De Bont reports that the bus jump stunt did not go as planned. To do the jump the bus had everything possible removed to make it lighter. On the first try the stunt driver missed the ramp and crashed the bus, making it unusable. This was not reported to the studio at the time. A second bus was prepared and two days later a second attempt was successful. But, again, things did not go as intended. Advised that the bus would only go about 20 feet, the director placed one of his multiple cameras in a position that was supposed to capture the bus landing. However, the bus traveled much farther airborne than anyone had thought possible. It crashed down on top of the camera and destroyed it. Luckily, another camera placed about 90 feet from the jump ramp recorded the event.

Filming of the final scenes occurred at Mojave Airport, which doubled for Los Angeles International Airport. The shots of the LACMTA Metro Red Line through the construction zone were shot using an 1/8 scale model of the Metro Red Line, except for the jump when it derailed.[14]

The MD520N helicopter used throughout the film, registration N599DB, Serial LN024, was sold to the Calgary Police Service[17] in 1995,[18] where it was in use until 2006; it was then sold to a private owner.[17]

Reception

Box office

Speed was released on June 10, 1994, in 2,138 theaters and debuted at the number one position, grossing $14.5 million on its opening weekend. It grossed $121.3 million domestically and $229.2 million internationally for a worldwide total of $350.5 million, well above its $30 million production budget.[1][2]

Critical response

Speed received positive reviews and has a "certified fresh" score of 94% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 65 reviews, with an average rating of 7.92/10. The critical consensus reads: "A terrific popcorn thriller, Speed is taut, tense, and energetic, with outstanding performances from Keanu Reeves, Dennis Hopper, and Sandra Bullock."[19] The film also has a score of 78 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 17 critics indicating "Generally favorable reviews."[20] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[21]

Roger Ebert gave the film four out of four stars and wrote, "Films like Speed belong to the genre I call Bruised Forearm Movies, because you're always grabbing the arm of the person sitting next to you. Done wrong, they seem like tired replays of old chase cliches. Done well, they're fun. Done as well as Speed, they generate a kind of manic exhilaration".[22] In his review for Rolling Stone magazine, Peter Travers wrote, "Action flicks are usually written off as a debased genre, unless, of course, they work. And Speed works like a charm. It's a reminder of how much movie escapism can still stir us when it's dished out with this kind of dazzle".[23] In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote, "Mr. Hopper finds nice new ways to convey crazy menace with each new role. Certainly he's the most colorful figure in a film that wastes no time on character development or personality".[24] Entertainment Weekly gave the film an "A" rating and Owen Gleiberman wrote, "It's a pleasure to be in the hands of an action filmmaker who respects the audience. De Bont's craftsmanship is so supple that even the triple ending feels justified, like the cataclysmic final stage of a Sega death match".[25] Time magazine's Richard Schickel wrote, "The movie has two virtues essential to good pop thrillers. First, it plugs uncomplicatedly into lurking anxieties—in this case the ones we brush aside when we daily surrender ourselves to mass transit in a world where the loonies are everywhere".[26] Filmmaker Quentin Tarantino named the film one of the twenty best films he had seen from 1992 to 2009.[27][28]

Entertainment Weekly magazine's Owen Gleiberman ranked Speed as 1994's eighth best film.[29] The magazine also ranked the film eighth on their "The Best Rock-'em, Sock-'em Movies of the Past 25 Years" list.[30] Speed also ranks 451 on Empire magazine's 2008 list of "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time".[31]

Mark Kermode of the BBC recalled having named Speed his film of the month working at Radio 1 at the time of release, and stated in 2017, having re-watched the film for the first time in many years, that it had stood the test of time and was a masterpiece.[32]

Home media

On November 8, 1994, Fox Video released Speed on VHS and LaserDisc formats for the very first time. Rental and video sales did very well and helped the film's domestic gross. The original VHS cassette was only available in standard 4/3 TV format at the time and in October 1996, Fox Video re-released a VHS version of the film in widescreen allowing the viewer to see the film in a similar format to its theatrical release. On November 3, 1999, 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment released Speed on DVD for the very first time. The DVD was in a widescreen format but, other than the film's theatrical trailer, the DVD contained no extras aside from the film. In 2002, Fox released a special collector's edition of the film with many extras and a remastered format of the film. Fox re-released this edition several times throughout the years with different covering and finally, in November 2006, Speed was released on a Blu-ray Disc format with over five hours of special features.

Accolades

Year-end lists

- 7th – Mack Bates, The Milwaukee Journal[33]

- 7th – John Hurley, Staten Island Advance[34]

- 9th – David Stupich, The Milwaukee Journal[35]

- 9th – Joan Vadeboncoeur, Syracuse Herald American[36]

- 9th – Michael Mills, The Palm Beach Post[37]

- 9th – Dan Craft, The Pantagraph[38]

- 9th – Christopher Sheid, The Munster Times[39]

- 10th – Bob Strauss, Los Angeles Daily News[40]

- 10th – Robert Denerstein, Rocky Mountain News[41]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Matt Zoller Seitz, Dallas Observer[42]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – William Arnold, Seattle Post-Intelligencer[43]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Eleanor Ringel, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution[44]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Steve Murray, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution[44]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Jeff Simon, The Buffalo News[45]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – Bob Carlton, The Birmingham News[46]

- Best "sleepers" (not ranked) – Dennis King, Tulsa World[47]

- "The second 10" (not ranked) – Sean P. Means, The Salt Lake Tribune[48]

- Top 3 Runner-ups (not ranked)nbsp;– Sandi Davis, The Oklahoman[49]

- Honorable mention – Mike Clark, USA Today[50]

- Honorable mention – Betsy Pickle, Knoxville News-Sentinel[51]

- Honorable mention – Duane Dudek, Milwaukee Sentinel[52]

- Honorable mention ("until the subway") – David Elliott, The San Diego Union-Tribune[53]

- Dishonorable mention – Glenn Lovell, San Jose Mercury News[54]

Awards

American Film Institute recognition:

- 100 Years...100 Thrills: No. 99[55]

- 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains: Jack Traven & Annie Porter - Nominated Heroes

Music

Soundtrack

A soundtrack album featuring "songs from and inspired by" the film was released on June 28, 1994 with the following tracks.[56] The soundtrack was commercially successful in Japan, being certified gold by the RIAJ in 2002.[57]

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Speed" | Billy Idol | 4:22 |

| 2. | "A Million Miles Away" | The Plimsouls | 3:41 |

| 3. | "Soul Deep" | Gin Blossoms | 3:06 |

| 4. | "Let's Go for a Ride" | Cracker | 3:07 |

| 5. | "Go Outside and Drive" | Blues Traveler | 4:51 |

| 6. | "Crash" | Ric Ocasek | 5:05 |

| 7. | "Rescue Me" | Pat Benatar | 3:01 |

| 8. | "Hard Road" | Rod Stewart | 4:28 |

| 9. | "Cot" | Carnival Strippers | 5:23 |

| 10. | "Cars ('93 Sprint Remix)" | Gary Numan | 4;02 |

| 11. | "Like a Motorway" | Saint Etienne | 5:43 |

| 12. | "Mr. Speed" | Kiss | 3:17 |

| Total length: | 50:04 | ||

Score

In addition to the soundtrack release, a separate album featuring 40 minutes of Mark Mancina's score from the film was released on August 30, 1994.[58] The CD track order does not follow the chronological order of the film's events.

La-La Land Records released a limited expanded version of Mark Mancina's score on February 28, 2012. The newly remastered release features 69:25 of music spread over 32 tracks (in chronological order). In addition, it includes the song "Speed" by Billy Idol.

Sequel

In 1997, a sequel, Speed 2: Cruise Control, was released. Sandra Bullock agreed to star again as Annie, for financial backing for another project, but Keanu Reeves declined the offer to return as Jack. As a result, Jason Patric was written into the story as Alex Shaw, Annie's new boyfriend, with her and Jack having broken up due to her worry about Jack's dangerous lifestyle. Willem Dafoe starred as the villain John Geiger, and Glenn Plummer (who played Reeves' carjacking victim) also cameos as the same character, this time driving a boat that Alex takes control of. The film is considered one of the worst sequels of all time, scoring only 4% (based on 69 reviews) on Rotten Tomatoes.[59]

See also

- The Bullet Train, a 1975 Japanese film in which a bomb will explode if a train slows down

- Runaway Train, a 1963 Akira Kurosawa screenplay with a similar premise that was later adapted into a 1985 Hollywood film

- The Doomsday Flight, a 1966 TV-movie in which a bomb will explode if a plane descends to land

Legacy

- MythBusters (2009 season), tested the reality of the iconic bus jump in the film

- The film is parodied in the UK Channel 4 sitcom Father Ted, in the episode "Speed 3", where Father Dougal drives a booby-trapped milk float that will explode if the speed falls below 4 mph.

- During the episode Boom! of the show Family Matters, which aired September 20, 1991, nearly three years before Speed was released, the episode featured Carl on a treadmill, which was booby-trapped to explode if he stepped off of it. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0577075/

- The film made a cameo in the 2020 Sonic the Hedgehog film.

References

- "Speed". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- Weinraub, Bernard (June 11, 1994). "Hurtling to the Top: A Director Is Born". The New York Times. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- Leong, Anthony. "Speed Movie Review". Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- Empire - Special Collectors' Edition - The Greatest Action Movies Ever (published in 2001)

- Bierly, Mandi (June 10, 2014). "'Speed' 20th anniversary: Screenwriter Graham Yost looks back". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- O'Hare, Kate (June 6, 2003). "The 'Bus Guy' triumphs". The Post-Star. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "Paul Attanasio Bio". iMDB.

- Kozak, Jim (August–September 2005). "Serenity Now!". In Focus. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Gerosa, Melina (June 10, 1994). "Speed Racer". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Bierly, Mandi (June 10, 2014). "'Speed' 20th anniversary: Screenwriter Graham Yost looks back". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- Svetkey, Benjamin (July 22, 1994). "Overdrive". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- McCabe, Bob (June 1999). "Speed". Empire. p. 121.

- "1979 Grumman Flxible 870 ADB in "Speed, 1994"". IMCDb.org. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- Dennis Hopper (host) (1994). The Making of 'Speed' (Documentary). 20th Century Fox.

- GJW. "Speed: Filming Locations - part 4".

- Mackie, Drew (June 13, 2014). "20 Reasons to Love Speed, 20 Years Later". People. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- "C-FCPS C-GCPS N599DB McDonnell Douglas MD520N C/N LN024".

- Service, Calgary Police (January 24, 2013). "Helicopter Air Watch for Community Safety HAWCS".

- "Speed (1994)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- "Speed". Metacritic.

- "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com.

- Ebert, Roger (June 10, 1994). "Speed". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- Travers, Peter (June 30, 1994). "Speed". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- Maslin, Janet (June 10, 1994). "An Express Bus in a Very Fast Lane". The New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Gleiberman, Owen (June 17, 1994). "Speed". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Schickel, Richard (June 13, 1994). "Brain Dead but Not Stupid". Time. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- Quentin Tarantino's Favourite Movies from 1992 to 2009... Quentin Tarantino interview Sky Movies at 4:30 via YouTube

- Brown, Lane (August 17, 2009). "Team America, Anything Else Among the Best Movies of the Past Seventeen Years, Claims Quentin Tarantino". Vulture. New York Magazine.

- Gleiberman, Owen (December 30, 1994). "The Best & Worst 1994/Movie". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- "The Action 25: The Best Rock-'em, Sock-'em Movies of the Past 25 Years". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on November 16, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- "The Need for Speed". December 8, 2017.

- Bates, Mack (January 19, 1995). "Originality of `Hoop Dreams' makes it the movie of the year". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 3.

- Hurley, John (December 30, 1994). "Movie Industry Hit Highs and Lows in '94". Staten Island Advance. p. D11.

- Stupich, David (January 19, 1995). "Even with gore, `Pulp Fiction' was film experience of the year". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 3.

- Vadeboncoeur, Joan (January 8, 1995). "Critically Acclaimed Best Movies of '94 Include Works from Tarantino, Burton, Demme, Redford, Disney and Speilberg". Syracuse Herald American (Final ed.). p. 16.

- Mills, Michael (December 30, 1994). "It's a Fact: 'Pulp Fiction' Year's Best". The Palm Beach Post (Final ed.). p. 7.

- Craft, Dan (December 30, 1994). "Success, Failure and a Lot of In-between; Movies '94". The Pantagraph. p. B1.

- Sheid, Christopher (December 30, 1994). "A year in review: Movies". The Munster Times.

- Strauss, Bob (December 30, 1994). "At the Movies: Quantity Over Quality". Los Angeles Daily News (Valley ed.). p. L6.

- Denerstein, Robert (January 1, 1995). "Perhaps It Was Best to Simply Fade to Black". Rocky Mountain News (Final ed.). p. 61A.

- Zoller Seitz, Matt (January 12, 1995). "Personal best From a year full of startling and memorable movies, here are our favorites". Dallas Observer.

- Arnold, William (December 30, 1994). "'94 Movies: Best and Worst". Seattle Post-Intelligencer (Final ed.). p. 20.

- "The Year's Best". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. December 25, 1994. p. K/1.

- Simon, Jeff (January 1, 1995). "Movies: Once More, with Feeling". The Buffalo News. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Carlton, Bob (December 29, 1994). "It Was a Good Year at Movies". The Birmingham News. p. 12-01.

- King, Dennis (December 25, 1994). "SCREEN SAVERS In a Year of Faulty Epics, The Oddest Little Movies Made The Biggest Impact". Tulsa World (Final Home ed.). p. E1.

- P. Means, Sean (January 1, 1995). "'Pulp and Circumstance' After the Rise of Quentin Tarantino, Hollywood Would Never Be the Same". The Salt Lake Tribune (Final ed.). p. E1.

- Davis, Sandi (January 1, 1995). "Oklahoman Movie Critics Rank Their Favorites for the Year "Forrest Gump" The Very Best, Sandi Declares". The Oklahoman. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- Clark, Mike (December 28, 1994). "Scoring with true life, `True Lies' and `Fiction.'". USA Today (Final ed.). p. 5D.

- Pickle, Betsy (December 30, 1994). "Searching for the Top 10... Whenever They May Be". Knoxville News-Sentinel. p. 3.

- Dudek, Duane (December 30, 1994). "1994 was a year of slim pickings". Milwaukee Sentinel. p. 3.

- Elliott, David (December 25, 1994). "On the big screen, color it a satisfying time". The San Diego Union-Tribune (1, 2 ed.). p. E=8.

- Lovell, Glenn (December 25, 1994). "The Past Picture Show the Good, the Bad and the Ugly -- a Year Worth's of Movie Memories". San Jose Mercury News (Morning Final ed.). p. 3.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills" (PDF). Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- "Speed: Songs From And Inspired By The Motion Picture (Soundtrack)". Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- "GOLD ALBUM 他認定作品 2002年2月度" [Gold Albums, and other certified works. February 2002 Edition] (PDF). The Record (Bulletin) (in Japanese). 509: 13. April 10, 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- "Speed: Original Motion Picture Score (Soundtrack)". Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- "Speed 2 - Cruise Control". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved August 4, 2013.