South Capitol Street

South Capitol Street is a major street dividing the southeast and southwest quadrants of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It runs south from the United States Capitol to the D.C.–Maryland line, intersecting with Southern Avenue. After it enters Maryland, the street becomes Indian Head Highway (Maryland Route 210) at the Eastover Shopping Center, a terminal or transfer point of many bus routes.

| South Capitol Street SW South Capitol Street SE | |

Looking north at the United States Capitol while standing on South Capitol Street | |

| Maintained by | DDOT |

|---|---|

| Width | 130 feet (40 m) (total width) 10 feet (3.0 m) (sidewalk)[1] |

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| South end | |

| Major junctions | Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue SE Suitland Parkway M Street Washington Avenue |

| North end | Independence Avenue |

| Construction | |

| Commissioned | 1791 |

| Completion | 1940 |

History

South Capitol Street from the United States Capitol to the Anacostia River was part of the L'Enfant Plan of streets for the District of Columbia. The Residence Act of 1790 gave President George Washington the authority to select the location for the national capital, and the area comprising the District of Columbia was chosen in late 1790.[2] A surveying commission was chosen in January 1791,[2] and in August 1791 Pierre Charles L'Enfant had delivered his plan for the city to Washington.[3] Construction of the segment of South Capitol Street from the Capitol to the Anacostia River occurred over the decade, as the roadway was surveyed, trees were felled, brush and stumps removed, a roadway graded, and the street later paved with a variety of surfaces (wood blocks, granite blocks, oiled earth, aggregate, and macadam).

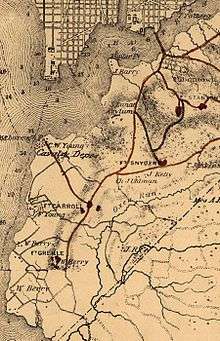

The area east of the Anacostia River remained mostly farms and forest with few roads. The area was served primarily by the Navy Yard Bridge, constructed in 1820.[4] The first residential development in the area was Uniontown (now the neighborhood of Anacostia), begun in 1854.[5] The following year, the federal government constructed the Government Hospital for the Insane (later known as St. Elizabeths Hospital). To serve the hospital, Asylum Avenue was constructed from the Navy Yard Bridge to the new hospital and then, running on the east side of a line of hills, down to the District–Maryland line.[6] Additional construction in the area occurred during the American Civil War (1861–1865). The United States Department of War constructed the George Washington Young cavalry magazine on 90 acres (360,000 m2) of land on Giesborough Point.[7] Two forts, Fort Carroll and Fort Greble, were constructed on the bluffs that began just west and adjacent to Asylum Road. After the war, the 375-acre (1,520,000 m2) Barry Farm housing development for freed slaves opened in 1867 and was rapidly occupied.[8] Aslyum Avenue was named Nichols Avenue in 1879 in honor of hospital superintendent Charles Henry Nichols.[9]

Asylum Avenue/Nichols Avenue was the only major southward road through the area until the 1890s, when the lower portion of South Capitol Street was constructed. A bridge connecting South Capitol Street to the area south of the Anacostia River was first proposed in 1889, but never acted on.[10] However, in 1890, Colonel Arthur E. Randle[lower-alpha 1][11] founded the settlement of Congress Heights.[12] The development was wildly successful, and he invested heavily in the Belt Railway, a local streetcar company.[13] In 1895, Randle founded the Capital Railway Company, which constructed streetcar lines over the Navy Yard Bridge and down Nichols Avenue to Congress Heights.[13][14][lower-alpha 2][14][15][16]

The rapid development of Congress Heights and the areas adjacent to the streetcar line on Nichols Avenue led the government of the District of Columbia to extend South Capitol Street into the area east of the Anacostia River. The topography of the area largely dictated the route. Beginning near St. Elizabeths Hospital, a line of bluffs extended roughly southward until it reached what is now Chesapeake Street SW. (Fort Greble sat atop the southernmost of these cliffs.) To the west of these bluffs were broad, flat lowlands which provided views of the Potomac River and the city of Alexandria, Virginia. In 1893, the city surveyed South Capitol along the western side of these bluffs, laying out a broad avenue.[7] Once the bluffs ended, the route followed existing local roads and curved eastward to connect with Livingston Road (now the Indian Head Highway) at the District-Maryland line. But because of the lack of development south of Congress Heights, South Capitol Street was only constructed to its intersection with Nichols Avenue.[17]

The two ends of South Capitol Street remained unconnected, however. Congress again considered building a South Capitol Street bridge in 1902 and 1926, but nothing came of these plans.[18][19] The Army Corps of Engineers finally extended South Capitol Street from Nichols Avenue to the District boundary in 1940.[17] Congress also approved a South Capitol Street bridge in 1940, but the onset of World War II prevented its funding and construction.[20]

The South Capitol Street bridge was finally constructed in 1949 at a cost of $5 million. It was dedicated to Frederick Douglass in October 1965.[20]

Route

North of the Anacostia River, South Capitol Street runs in a straight north–south line. South Capitol Street begins at Southwest Drive, an access road on the south side of the grounds of the United States Capitol. It travels a half block south, and crosses Independence Avenue. Since roads on the grounds of the Capitol are closed to the public, this intersection has traditionally been the beginning of South Capitol Street. It widens from a two-lane to four-lane thoroughfare just before reaching Washington Avenue SE, and then passes beneath Interstate 695. Northbound traffic on South Capitol Street may access Interstate 695 westbound, and eastbound Interstate 695 traffic may leave the elevated highway and access southbound South Capitol Street. South Capitol Street passed beneath M Street SE/SW via an underpass, although access roads on both sides of South Capitol Street provide service either way on M Street. South Capitol Street bifurcates alongside Nationals Park, home of the Washington Nationals major league baseball team. Its last intersection north of the Anacostia River is with Potomac Avenue SE.

South Capitol Street crosses the Anacostia via the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge, which is angled on a northwest–southeast line so that the bridge's southwest terminus does not occur on land owned by Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling. A "mixing bowl" of off- and on-ramps provides access to southbound Suitland Parkway, with an adjacent cloverleaf interchange giving access to Firth Sterling Avenue and the Anacostia Washington Metro station as well as northbound Interstate 295. South Capitol Street then follows a winding path along the eastern border of Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling. Deceleration lanes provide access to Malcolm X Avenue SE and the main gates of Joint Base Anacostia–Bolling and Interstate 295 again. South Capitol Street angles south-southeast at Overlook Avenue SW, passing below Interstate 295 and continues winding south-southeast until it reaches Southern Avenue. It is coterminous with Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue SE for a single block between Halley Place SE and 2nd Street SW before winding toward Southern Avenue and the District boundary line.

The section of South Capitol Street between Washington Avenue SW and Suitland Parkway is part of the National Highway System.

South Capitol Street forms the north-northeastern boundary of Oxon Run Park

Taxation Without Representation Street

The D.C. City Council attempted to rename a portion of South Capitol Street adjacent to Nationals Park in 2008 as "Taxation Without Representation Street" in order to bring attention to the city's lack of voting rights in Congress.[21] The goal, according to advocates, was to boost awareness by changing the address of Nationals Park.[22] The name change required congressional approval. Congress failed to act on the bill, and it never became law.

References

- Notes

- Randle, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, received the commission of colonel in the Mississippi State Militia from Andrew H. Longino, Governor of the state of Mississippi, in 1902.

- The Capitol, North O Street, and South Washington Railway Company was chartered by Congress on March 3, 1875. By act of Congress enacted on February 18, 1893, it changed its name to the Belt Railway. The Belt Railway was purchased on June 24, 1898, by the Anacostia and Potomac River Railway Company, which itself had been founded on May 19, 1872, but not chartered by Congress until February 18, 1875. Randle founded the Capital Railway Company on March 2, 1895, to own and construct the extension to Congress Heights, and made it a division of the Anacostia and Potomac River Railway in 1899. The Washington Railway and Electric Company purchased a controlling share in the Anacostia and Potomac River Railway on August 31, 1912.

- Citations

- National Capital Planning Commission and the District of Columbia Office of Planning & January 2003, p. 22.

- Reps 1965, p. 240-242.

- Stewart 1898, p. 52.

- Croggon, James (July 7, 1907). "Old 'Burnt Bridge'". Washington Evening Star.

- Burr 1920, pp. 171–172.

- Benedetto, Du Vall & Donovan 2001, p. 201.

- Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce 1894, p. 3.

- Davidson & Malloy 2009, pp. 132–133.

- Evelyn, Dickson & Ackerman 2008, p. 286.

- "The Proposed New Bridge". The Washington Post. September 3, 1889; "Mr. Clarke Complains". The Washington Post. January 11, 1890.

- "Col. Randle Kills Self in California". The Washington Post. July 5, 1929.

- General Services Administration 2012, p. 4—27.

- Proctor, Black & Williams 1930, p. 732.

- "Electric Railways". Municipal Journal & Public Works. February 26, 1908. p. 252.

- Fennell 1948, p. 15.

- Tindall 1918, pp. 39-41.

- "Plans for Street Projects Told By Whitehurst". The Washington Post. September 24, 1940.

- "Bridge to Congress Heights". The Washington Post. June 10, 1902.

- Gutheim & Lee 2006, p. 208.

- Myer 1974, p. 42.

- Gresko, Jessica (January 13, 2011). "D.C. Protest: Talk of Renaming Pennsylvania Avenue". The Associated Press.

- "Nats' Address May Become 'Taxation Without Representation Street'". WTOP. November 25, 2008. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

Bibliography

- Benedetto, Robert; Du Vall, Kathleen; Donovan, Jane (2001). Historical Dictionary of Washington, D.C. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810840942.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burr, Charles R. (1920). "A Brief History of Anacostia, Its Name, Origin, and Progress". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. The Society.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce (1894). "Survey of a Bridge Across the Eastern Branch of the Potomac. Senate Report No. 1210. 53rd Cong., 2d sess.". The Reports of the Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Fifty-Third Congress, 1893-94. Vol. 4. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davidson, Nestor M.; Malloy, Robin Paul (2009). Affordable Housing and Public-Private Partnerships. Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754694380.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evelyn, Douglas E.; Dickson, Paul; Ackerman, S.J. (2008). On This Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, D.C. Sterling, Va.: Capital Books. ISBN 9781933102702.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fennell, Margaret L. (1948). Corporations Chartered By Special Act of Congress. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- General Services Administration (2012). Department of Homeland Security Headquarters Consolidation at St. Elizabeths Master Plan Amendment, East Campus North Parcel: Environmental Impact Statement. Washington, D.C.: General Services Administration.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gutheim, Frederick A.; Lee, Antoinette (2006). Worthy of the Nation: Washington, D.C., From L'Enfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801883286.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Myer, Donald Beekman (1974). Bridges of the City of Washington. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Commission of Fine Arts.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- National Capital Planning Commission and the District of Columbia Office of Planning (January 2003). South Capitol Street Urban Design Study (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Capital Planning Commission.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Proctor, John Clagett; Black, Frank P.; Williams, E. Melvin (1930). Washington, Past and Present: A History. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reps, John William (1965). The Making of Urban America. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691006180.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart, John (1898). "Early Maps and Surveyors of the City of Washington, D.C". Records of the Columbia Historical Society. Retrieved May 4, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tindall, William (1918). "Beginnings of Street Railways in the National Capital". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C.: 24–86.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)