Somatic anxiety

Somatic anxiety, also known as somatization, is the physical manifestation of anxiety.[1] It is commonly contrasted with cognitive anxiety, which is the mental manifestation of anxiety, or the specific thought processes that occur during anxiety, such as concern or worry. These different components of anxiety are especially studied in sports psychology,[2] specifically relating to how the anxiety symptoms affect athletic performance.

"Symptoms typically associated with somatization of anxiety and other psychiatric disorders include abdominal pain, dyspepsia, chest pain, fatigue, dizziness, insomnia, and headache."[1] These symptoms can either happen alone or multiple can happen at once.

Somatic anxiety is often pushed to the side and is not being treated as seriously as other forms of anxiety. This is including sayings like "butterflies in my stomach."[3] A lot of people someway relate their pain to the culture they were raised in. An example given by Charlotte Hanlon and Abebaw Fekeddu was that someone of sub-Saharan African descent might describe their somatic pain as burning or crawling sensations all over the body.[3]

Children with this disorder tend to decline tremendously in school. This disorder also has the effect to make the person want to stop attending social events and activities. Most of the time, a child is sent to see a regular physician but in some cases a specialist is required. A common suggestion is to try to make the child attend social activities.

Increasing evidence shows that adults with this disorder often experienced it during their childhood years.[3] Some symptoms tend to be the same for adults struggling with social anxiety.

Although commonly overlooked, scientists are starting to study somatic anxiety more. Studies are actually starting to show that some medically overlooked cases that could not relate physical pain to any type of organ dysfunction typically could have been somatic anxiety.[1]

Anxiety-performance relationship theories

Drive theory

The Drive Theory (Zajonc 1965)[4] says that if an athlete is both skilled and driven (by somatic and cognitive anxiety) then the athlete will perform well.[5]

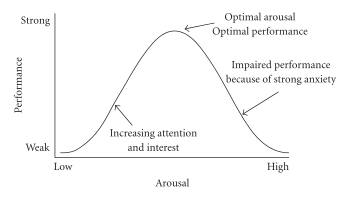

Inverted-U hypothesis

The Inverted-U Hypothesis (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908),[6] also known as the Yerkes-Dodson law (Yerkes 1908)[6] hypothesizes that as somatic and cognitive anxiety (the arousal) increase, performance will increase until a certain point. Once the arousal has increased past this point, performance will decrease.[5]

Multi-dimensional theory

The Multi-dimensional Theory of Anxiety (Martens, 1990)[7] is based on the distinction between somatic and cognitive anxiety. The theory predicts that there is a negative, linear relationship between somatic and cognitive anxiety, that there will be an Inverted-U relationship between somatic anxiety and performance, and that somatic anxiety should decline once performance begins although cognitive anxiety may remain high, if confidence is low.[8]

Catastrophe theory

The Catastrophe Theory (Hardy, 1987)[9] suggests that stress, combined with both somatic and cognitive anxiety, influences performance, that somatic anxiety will affect each athlete differently, and that performance will be affected uniquely, which will make it difficult to predict an outcome using general rules.[8]

Optimum arousal theory

The Optimum Arousal Theory (Hanin, 1997)[10] states that each athlete will perform at their best if their level of anxiety falls within an "optimum functioning zone".[5]

See also

References

- Gelenberg, A. J (2000). "Psychiatric and Somatic Markers of Anxiety: Identification and Pharmacologic Treatment". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2 (2): 49–54. doi:10.4088/PCC.v02n0204. PMC 181205. PMID 15014583.

- Rainer Martens; Robin S. Vealey; Damon Burton (1990), Competitive anxiety in sport, pp. 6 et seq, ISBN 9780873229357

- "Somatic anxiety". ScienceDirect.

- Zajonc, Robert B (1965). "Social Facilitation". Science. 149 (3681): 269–74. doi:10.1126/science.149.3681.269. JSTOR 1715944. PMID 14300526.

- "Competitive Anxiety". BrianMac. May 3, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- Yerkes, Robert M; Dodson, John D (1908). "The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology. 18 (5): 459–482. doi:10.1002/cne.920180503.

- Martens, R. et al. (1990) The Development of the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2). Human Kinetics

- McNally, Ivan M. (August 2002). "Contrasting Concepts of Competitive State-Anxiety in Sport: Multidimensional Anxiety and Catastrophe Theories". Athletic Insight. 4 (2): 10–22. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.629.5627.

- Hardy, L. & Fazey, J. (1987). The Inverted-U Hypothesis: A Catastrophe For Sport Psychology? Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the North American Society for the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity. Vancouver. June 1987.

- Hanin, Yuri L. (2003-01-31). "Performance Related Emotional States in Sport: A Qualitative Analysis". Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 4 (1). ISSN 1438-5627.

Additional references

- Schwartz, Gary E; Davidson, Richard J; Goleman, Daniel J (1978). "Patterning of Cognitive and Somatic Processes in the Self-Regulation of Anxiety: Effects of Meditation versus Exercise". Psychosomatic Medicine. 40 (4): 321–328. doi:10.1097/00006842-197806000-00004. PMID 356080.