Solar cycle 23

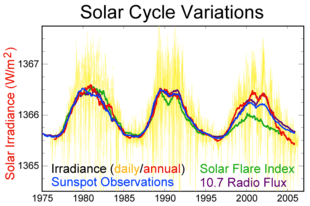

Solar cycle 23 was the 23rd solar cycle since 1755, when extensive recording of solar sunspot activity began.[1][2] The solar cycle lasted 12.3 years, beginning in August 1996 and ending in December 2008. The maximum smoothed sunspot number (SIDC formula) observed during the solar cycle was 180.3 (November 2001), and the starting minimum was 11.2.[3] During the minimum transit from solar cycle 23 to 24, there were a total of 817 days with no sunspots.[4][5][6] Compared to the last several solar cycles, it was fairly average in terms of activity.

| Solar cycle 23 | |

|---|---|

The Sun, with some sunspots visible, during solar cycle 23 (2003). | |

| Sunspot data | |

| Start date | August 1996 |

| End date | December 2008 |

| Duration (years) | 12.3 |

| Max count | 180.3 |

| Max count month | November 2001 |

| Min count | 11.2 |

| Spotless days | 817 |

| Cycle chronology | |

| Previous cycle | Solar cycle 22 (1986–1996) |

| Next cycle | Solar cycle 24 (2008-late 2019) |

History

Large solar flares occurred on 7 September 2005 (X17), 15 April 2001 (X14.4) and 29 October 2003 (X10), with auroras visible in mid-latitudes.

2000

One of the first major aurora displays of solar cycle 23 occurred on 6 April 2000, with bright red auroras visible as far south as Florida and South Europe.[7] On 14 July 2000, the Coronal Mass Ejection (CME) hurled by a X5.7 solar flare provoked an extreme (G5 level) geomagnetic storm the next day. Known as the Bastille Day event, this storm caused damage to GPS systems and some power companies. Auroras were visible as far south as Texas.[8]

2001

Another major aurora display was observed on 1 April 2001, due to a coronal mass ejection hitting the Earth's magnetosphere. Auroras were observed as far south as Mexico and South Europe. A large solar flare (the second-most powerful ever recorded) occurred on 2 April 2001, an X20-class, but the blast was directed away from Earth.

2003

In late October 2003, a series of large solar flares occurred. A X17.2-class flare ejected on 28 October 2003 produced auroras visible as far south as Florida and Texas. A G5 level geomagnetic storm blasted the Earth's magnetosphere over the next two days.[9] A few days later, the largest solar flare ever measured with instruments occurred on 4 November; initially measured at X28, it was later upgraded to an X45-class.[10][11] This flare was not Earth-oriented and thus only resulted in high-latitude auroras. The whole sequence of events that occurred from 28 October to 4 November is known as the Halloween Solar Storm.

See also

References

- Kane, R.P. (2002), "Some Implications Using the Group Sunspot Number Reconstruction", Solar Physics, 205 (2): 383–401, Bibcode:2002SoPh..205..383K, doi:10.1023/A:1014296529097

- "The Sun: Did You Say the Sun Has Spots?". Space Today Online. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- "SIDC Monthly Smoothed Sunspot Number".

- "Spotless Days".

- Dr. Tony Phillips (11 July 2008). "What's Wrong with the Sun? (Nothing)". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2008.

- "Solaemon's Spotless Days Page".

- "Brushfires in the Sky". nasa.gov. 25 April 2000. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- "A Solar Radiation Storm". nasa.gov. 14 July 2000. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- "Hotshot". nasa.gov. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- "Hotshot". nasa.gov. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- "Biggest ever solar flare was even bigger than thought". spaceref.com. 15 March 2004. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

External links

- "The Most Powerful Solar Flares Ever Recorded". spaceweather.com. Retrieved 18 November 2010.