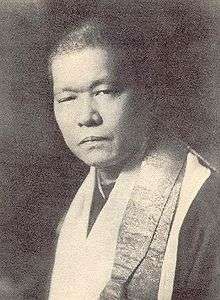

Sokei-an

Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki (佐々木 指月 (曹渓庵); March 10, 1882 – May 17, 1945), born Yeita Sasaki (佐々木 栄多), was a Japanese Rinzai monk who founded the Buddhist Society of America (now the First Zen Institute of America) in New York City in 1930. Influential in the growth of Zen Buddhism in the United States, Sokei-an was one of the first Japanese masters to live and teach in America. In 1944 he married American Ruth Fuller Everett. He died in May 1945 without leaving behind a Dharma heir. One of his better known students was Alan Watts, who studied under him briefly. Watts was a student of Sokei-an in the late 1930s.[1]

Sokei-an Sasaki | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Roshi |

| Personal | |

| Born | Yeita Sasaki March 10, 1882 |

| Died | May 17, 1945 (age 63) |

| Religion | Zen Buddhism |

| Spouse | Tomé Sasaki Ruth Fuller Sasaki |

| Children | Shintaro Seiko Shioko |

| School | Rinzai |

| Education | Imperial Academy of Art (Tokyo) California Institute of Art |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Sokatsu Shaku Soyen Shaku |

| Based in | Buddhist Society of America |

| Predecessor | Sokatsu Shaku |

| Successor | None |

Students

| |

| Website | www.firstzen.org/ |

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Persons Chán in China Classical

Contemporary

Zen in Japan Seon in Korea Thiền in Vietnam Zen / Chán in the USA Category: Zen Buddhists |

|

Doctrines

|

|

Awakening |

|

Practice |

|

Schools

|

|

Related schools |

| Part of a series on |

| Western Buddhism |

|---|

.jpeg) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exchange

|

|

General Buddhism

|

Biography

Sokei-an was born in Japan in 1882 as Yeita Sasaki. He was raised by his father, a Shinto priest, and his father's wife, though his birth mother was his father's concubine. Beginning at age four, his father taught him Chinese and soon had him reading Confucian texts.[2] Following the death of his father when he was fifteen, he became an apprentice sculptor and came to study under Japan's renowned Koun Takamura at the Imperial Academy of Art in Tokyo.[3] While in school he began his study of Rinzai Zen under Sokatsu Shaku, (a Dharma heir of Soyen Shaku), graduating from the academy in 1905.[2] Following graduation he was drafted by the Japanese Imperial Army and served briefly during the Russo-Japanese War on the border of Manchuria. Sasaki was discharged when the war ended shortly after in 1906, and soon married his first wife, Tomé, a fellow student of Sokatsu.[4] The newlyweds followed Sokatsu to San Francisco, California that year as part of a delegation of fourteen. The couple soon had their first child, Shintaro. In California with the hope of establishing a Zen community, the group farmed strawberries in Hayward, California with little success. Sasaki then studied painting under Richard Partington[2] at the California Institute of Art, where he met Nyogen Senzaki.[3] By 1910 the delegation's Zen community had proven unsuccessful. All members of the original fourteen, with the exception of Sasaki, made return trips back to Japan.[3][4]

Sokei-an then moved to Oregon without Tomé and Shintaro to work for a short while, being rejoined by them in Seattle Washington (where his wife gave birth to their second child, Seiko,[2] a girl). In Seattle, Sasaki worked as a picture frame maker[2] and wrote various articles and essays for Japanese publications such as Chuo Koron and Hokubei Shinpo. He traveled the Oregon and Washington countrysides selling subscriptions to Hokubei Shinpo.[2] His wife, who had become pregnant again, moved back to Japan in 1913 to raise their children. Over the next few years he made a living doing various jobs, when in 1916 he moved to Greenwich Village in Manhattan, New York, where he encountered the poet and magus Aleister Crowley.[5] Sometime during this period he was interviewed by the US Army but not drafted due to lingering allegiances to Japan.[6] In New York he worked both as a janitor and a translator for Maxwell Bodenheim. He also began to write poetry during his free time.[4] He returned to Japan in 1920 to continue his koan studies, first under Soyen Shaku and then with Sokatsu.[3] In 1922 he returned to the United States and in 1924 or 1925 began giving talks on Buddhism at the Orientalia Bookstore on E. 58th Street in New York City, having received lay teaching credentials from Sokatsu. In 1928 he received inka from Sokatsu in Japan, the "final seal" of approval in the Rinzai school.[3] Then, on May 11, 1930, Sokei-an and some American students founded the Buddhist Society of America, subsequently incorporated in 1931,[7] at 63 West 70th Street (originally with just four members).[8] Here he offered sanzen interviews and gave Dharma talks, also working on various translations of important Buddhist texts.[4] He made part of his living by sculpting Buddhist images and repairing art for Tiffany's.[9]

In 1938 his future wife, Ruth Fuller Everett, began studying under him and received her Buddhist name (Eryu); her daughter, Eleanor, was then the wife of Alan Watts (who also studied under Sokei-an that same year).[10] In 1941 Ruth purchased an apartment at 124 E. 65th Street in New York City, which also served as living quarters for Sokei-an and became the new home for the Buddhist Society of America (opened on December 6). Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Sokei-an was arrested by the FBI as an "enemy alien"[4] taken to Ellis Island on June 15 and then interned at a camp in Fort Meade, Maryland on October 2, 1942 (where he suffered from high blood pressure and several strokes). He was released from the internment camp on August 17, 1943 following the pleas of his students and returned to the Buddhist Society of America in New York City. In 1944 he divorced his wife in Little Rock, Arkansas, with whom he had been separated for several years. Soon after, on July 10, 1944, Sokei-an married Ruth Fuller Sasaki in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Sokei-an died on May 17, 1945 after years of bad health.[4] His ashes are interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York.[11] The Buddhist Society of America underwent a name change following his death in 1945, becoming the First Zen Institute of America.[12]

Teaching style

Sokei-an's primary way of teaching Zen Buddhism was by means of sanzen, "an interview during which the teacher would set the student a koan"[13]—and his Dharma talks were often delivered in the form of a teisho.[14] Sokei-an did not provide instruction in zazen or hold sesshins at the Buddhist Society of America. His primary focus was on koans and sanzen, relying on the Hakuin system.[15] According to Mary Farkas, "Sokei-an had no interest in reproducing the features of Japanese Zen monasticism, the strict and regimented training that aims at making people 'forget self.' In these establishments, individuality is stamped out, novices move together like a school of fish, their cross-legged position corrected with an ever-ready stick."[16]

Miscellaneous

Dwight Goddard (author of "A Buddhist Bible") has described Sokei-an as, "being from the autocratic and blunt 'old school' of Zen masters."[9] According to writer Robert Lopez, "Sokei-an lectured on Zen and Buddhism in English. But he communicated the essence of the Buddha’s teaching and in his daily life by his presence alone, in silence, and in a radiance achieved through, as he once said, 'nature’s orders.'"[4] Alan Watts has said of Sokei-an, "I felt that he was basically on the same team as I; that he bridged the spiritual and the earthy, and that he was as humorously earthy as he was spiritually awakened."[10] In his autobiography, Watts had this to say, "When he began to teach Zen he was still, as I understand, more the artist than the priest, but in the course of time he shaved his head and 'sobered up.' Yet not really. For Ruth was often apologizing for him and telling us not to take him too literally or too seriously when, for example, he would say that Zen is to realize that life is simply nonsense, without meaning other than itself or future purpose beyond itself. The trick was to dig the nonsense, for—as Tibetans say—you can tell the true yogi by his laugh."[17] Zen master Dae Gak has said, "Sokei-An has a good understanding of Western culture and this, combined with his enlightened perspective, is a trustworthy bridge from Zen in the East to Zen in the West. He finds that place where "East" and "West" no longer exist and articulates this wisdom brilliantly for all beings. A true bodhisattva."[18]

Notable students

- Alan Watts ("He (Watts) left after two weeks frustrated with the koan work he was doing."[19])

- Mary Farkas

- Ruth Fuller Sasaki

- Samuel L. Lewis

See also

References

- Shansky, Albert (2015). An American's Journey into Buddhism. McFarland. p. 214. ISBN 9780786484249.

- Stirling, 31-35

- Ford, 66-67

- Lopez

- The International [v12 # 2 and 4, 1918] ed. George Sylvester Viereck

- Sasaki, "Excluded Japanese and Exclusionary Americans" in Rediscovering America, p. 75.

- Prebish, 10

- Smith, Novack; 150-151

- Stirling, 20

- Tweti

- Stirling, 253-254

- Miller, 163

- Lachman, 114

- Skinner Keller, 638

- Watts, 134

- Farkas, 1

- Watts, 135

- Sokei-An Shigetsu Sasaki (1998-04-01). Zen Pivots: Lectures On Buddhism And Zen. Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0416-6.

- "Watts, Alan". sweepingzen.com. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

Bibliography

- Delp, Michael (1997). The Coast of Nowhere: Meditations on Rivers, Lakes, and Streams. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-2711-7. OCLC 36942529.

- Farkas, Mary; Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki (1993). The Zen Eye: A Collection of Zen Talks by Sokei-an. Tokyo; New York: Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0272-4. OCLC 27266361.

- Ford, James Ishmael; James Ishmael Ford (2006). Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-509-8. OCLC 70174891.

- Lachman, Gary (2003). Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius. The Disinformation Company. ISBN 0-9713942-3-7. OCLC 52384670.

- Lopez, Robert (Spring 1997). "Zen in the Yawn of a Cat: Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Archived from the original on May 7, 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- Miller, Timothy (1995). America's Alternative Religions. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-2397-2. OCLC 30476551.

- Prebish, Charles S (1999). Luminous Passage: The Practice and Study of Buddhism in America. University of California Press. pp. 32, 33, 34. ISBN 0-520-21697-0.

- Skinner Keller, Rosemary; Rosemary Radford Ruether; Marie Cantlon (2006). The Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34685-1. OCLC 61711172.

- Smith, Huston; Philip Novak (2004). Buddhism: A Concise Introduction. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-073067-6. OCLC 57307393.

- Stirling, Isabel (2006). Zen Pioneer: The Life & Works of Ruth Fuller Sasaki. Shoemaker & Hoard Publishers. ISBN 1-59376-110-4. OCLC 65165357.

- Tweti, Mira (2007-08-06). "The Sensualist". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Archived from the original on 2007-10-31. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- Watts, Alan (2007). In My Own Way: An Autobiography, 1915-1965. New World Library. ISBN 1-57731-584-7. OCLC 84838304.

- Sasaki, Sokei-an Shigetsu (2011). "Excluded Japanese and Exclusionary Americans". In Duus, Peter (ed.). Rediscovering America: Japanese Perspectives on the American Century. University of California Press. pp. 69–76. ISBN 0520268431.

Further reading

- Farkas, Mary; Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki (1993). The Zen Eye: A Collection of Zen Talks by Sokei-an. Tokyo; New York: Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0272-4. OCLC 27266361.

- Farkas, Mary; Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki; Robert Lopez (1998). Zen Pivots: Lectures on Buddhism and Zen. New York: Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0416-6. OCLC 38120661.

- Fields, Rick (1981). How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America. Shambhala Publications/Random House. ISBN 0-87773-208-6. OCLC 7571910.

- Hotz, Michael; Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki (2003). Holding the Lotus to the Rock: The Autobiography of Sokei-an, America's First Zen Master. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 1-56858-248-X. OCLC 51203880.

- Sasaki, Sokei-an Shigetsu (1947). Cat's Yawn: The Thirteen Numbers Published from 1940 to 1941. New York: First Zen Institute of America. OCLC 21917701.

- Sasaki, Sokei-an Shigetsu (1931). The Story of the Giant Disciples of Buddha; Ananda and Maha-Kasyapa. First Zen Institute of America. OCLC 39794012.

- Sasaki, Sokei-an Shigetsu (1931). The Story of the Giant Disciples of Buddha; Ananda and Maha-Kasyapa. First Zen Institute of America. OCLC 39794012.