Sokaogon Chippewa Community

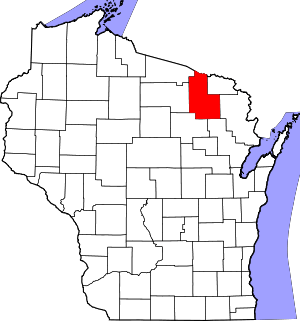

The Sokaogon Chippewa Community, or the Mole Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, is a band of the Lake Superior Chippewa, many of whom reside on the Mole Lake Indian Reservation, located at 45°29′52″N 88°59′20″W in the Town of Nashville, in Forest County, Wisconsin. The reservation is located partly in the community of Mole Lake, Wisconsin, which lies southwest of the city of Crandon.

The Mole Lake Indian Reservation is 4,904.2 acres (1984.7 ha) in size, and includes land around Rice Lake, Bishop Lake, and Mole Lake.[1] About 500 members of the tribe live on the reservation, while an additional 1,000 members of the community live off it. The tribe is active in the harvest of wild rice in the swampy areas on and off their reservation.[2]

History

The area was the site of the 1806 Battle of Mole Lake between Chippewa and Sioux warriors.

The constitution and by-laws of the Sokaogon Chippewa Community were approved November 9, 1938, and the charter was approved October 7, 1939 as part of the Indian Reorganization Act.[3]

The 1983 decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in the Lac Courte Oreilles v. Lester B. Voigt case, commonly called the Voigt decision, reaffirmed that the Sokaogon and other Chippewa tribes in northern Wisconsin should be allowed to exercise their treaty rights even off their reservations.[4] This allowed the Sokaogon to harvest rice even on areas that the tribe did not own.

Mole Lake is the site of one of Wisconsin's oldest surviving log cabins, now referred to as the Dinesen Log House. This special piece of historic American architecture built in the late 1860s–early 1870s was listed on Wisconsin's most endangered properties in 2003 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. It has undergone a complete restoration and opened to the public in April 2010.[5]

In the early 1870s, Wilhelm Dinesen, a Danish adventurer, traveled to northern Wisconsin and took residence in the cabin and became friends with the Mole Lake Chippewa. He called the cabin "Frydenlund", or "Grove of Joy". After 14 months of hunting, fishing, fur trapping, and roaming the wilderness, went back to Denmark.[6] He fathered a daughter when he returned to his homeland, who grew up as the author Karen Blixen, or Isak Dinesen and wrote a book entitled Out of Africa, which went on to become a major Hollywood motion picture.

As stated in the April 2003 issue of Wisconsin Trails magazine, "Wilhelm Dinesen's legacy among the Chippewa is assured. A few months after he left Denmark, you see, Kate, the Chippewa woman who had been his cook and housekeeper, bore a daughter, Emma, who went on to have children of her own."[7]

The log cabin will be the center of an annual August event and visitors may see and hear history, folk music, enjoy traditional Native American food, Native American arts and crafts, Woodland Indian beadwork, birch bark basketry, and buckskin moccasin demonstrations, wild rice soup, introduction to the Ojibwe language, walk-through of historical displays, early fur trappers and traders camp and more. This event promises to be the beginning of a new era of opportunity for Wisconsin and its citizens.[8]

Resistance to proposed Exxon mine

In the late 1960s, Exxon discovered a zinc-copper ore deposit near Mole Lake, one of the richest ore deposits of its kind in North America. In 1976, Exxon announced its plans to explore the zinc-copper resources, which were in close proximity to four indigenous communities (including rice fields used by the Sokaogon Chippewa).[9] The proposed mining spurred a controversy lasting three decades. "From the perspective of the area's Indian tribes—the Sokaogon Chippewa, the Potawatomi, the Menominee, and the Stockbridge Munsee—the environmental and social impacts of the proposed mine were inseparable. Any contamination of the area's surface of groundwaters was a threat to survival."[10] Concerns about the impact of the proposed mine were diverse. In addition to the Sokaogan Chippewa's concerns regarding the impact of the mine on their wild rice fields, further downstream, the Menominee took issue with the "3000 gallons of wastewater per minute" the mine was predicted to release into a tributary leading to the Wolf River.[11]

Along with the neighboring Forest County Potawatomi Community, the Sokaogon Chippewa took over ownership and bought the nearby Crandon mine at a price of $16.5 million to prevent its reopening. The tribes argued that the opening of the zinc and copper mine would harm the environment and jeopardize access to their rice fields. The land is now under the control of the two tribes and no mining is planned into the future.[12]

References

- Profile from the State of Wisconsin

- Profile from the EPA

- Cohen, Felix (1942). Handbook of Federal Indian Law. Washington D.C.: U.S. GPO. pp. 129 – via HathiTrust.

- Moving Beyond Argument: Racism and Treaty Rights. Odanah Wisconsin: Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, 1989.

- Loohauis-Bennett, Jackie (2 April 2010). "Cabin restored to 1860s glory". JSOnline, Milwaukee Wisconsin Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Wilhelm Dinesen in America". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Wilhelm Dinesen's Grandchildren". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Help Restore the Historic Log Cabin". Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- Gedicks, Al (1993). The New Resource Wars. Boston: South End Press. p. 61.

- Gedicks, Al (1993). The New Resource Wars. Boston: South End Press. p. 63.

- Gedicks, Al (1993). The New Resource Wars. Boston: South End Press. p. 66.

- http://grist.org/article/wiltenburg2/