So Far from the Bamboo Grove

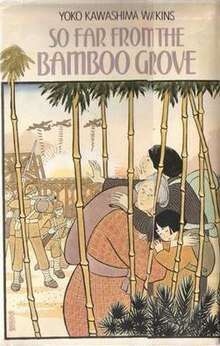

So Far from the Bamboo Grove is a semi-autobiographical novel written by Yoko Kawashima Watkins, a Japanese American writer.[1] It was originally published by Beech Tree in April 1986.

First edition | |

| Author | Yoko Kawashima Watkins |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Leo & Diane Dillon |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | War novel, Autobiographical novel |

| Publisher | William Morrow |

Publication date | April 1986 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 192 pp |

| ISBN | 978-0-688-13115-9 |

| OCLC | 426064992 |

| LC Class | PZ7.W3235 So 1994 |

| Followed by | My Brother, My Sister, and I |

Watkins's book takes place in the last days of 35 years of Korea's annexation by Japan. An eleven-year-old Japanese girl, Yoko Kawashima, whose father works for the Japanese government, must leave her home in Nanam, part of northern Korea, as her family escapes south to Seoul, then to Busan, to return to Japan.

Plot summary

The story begins with Yoko Kawashima (and her mother, brother and sister) living in Nanam. Yoko is 11 years old and living in North Korea during World War II while their father works as a Japanese government official in Manchuria, China. As the War draws towards a close, Yoko and her family realizes the danger of their situation and attempts to escape back to Japan as Communists troops close in on North Korea.

Her brother, Hideyo, also tries to leave but he is separated from his family because he has to serve at an ammunition factory for six days a week. The women of the family board a train to Seoul using a letter from a family diplomat but their trip is cut short by a bomb 45 miles away from Seoul. Yoko is injured from the bombing and the women are forced to walk the rest of the way. After receiving medical treatment in Seoul, Yoko, her sister, and mother board a train to Busan, and then a ship to Japan.

When Yoko, her sister Ko, and her mother reach Fukuoka, Japan, it is not the beautiful, comforting, welcoming place Yoko dreamed of. Once again, they find themselves living in a train station scrounging in the garbage for food to survive. Eventually, Yoko's mother travels to Kyoto to find her family. She then leaves for Aomori to seek help from their grandparents who she discovers are both dead. Their mother dies on the same day, leaving Yoko and Ko waiting for their brother Hideyo. Their mother's last words were to keep their wrapping cloth where she had hidden money for her children.

Yoko begins to attend a new school where she enters and wins an essay contest with a cash prize. News of her winning the contest is reported in the newspaper. Hideyo and the Korean family who took bid farewell and Hideyo finally reaches Busan where he finds the message left to him by Yoko. After reaching Japan, he sees signs with his name and Yoko and Ko's address. While asking directions from locals, he is spotted by Yoko and they are reunited.

Kawashima also wrote a sequel titled My Brother, My Sister, and I.

Translations

A Korean version of this book titled Yoko iyagi (요코이야기, "Yoko's tale") was published in 2005 and sold 4,000 copies of the first printing.[2] However, it was banned soon after.

A Japanese version of this book, Takebayashi haruka tōku : Nihonjin shōjo Yōko no sensō taikenki (竹林はるか遠く : 日本人少女ヨーコの戦争体験記, "Bamboo grove far distant: Japanese girl Yōko's war experience account") became available in June 2013.[3] As of June 7, 2013, the book was at No. 1 on the Amazon Best Sellers in Books in Japan.[4]

Controversy

Response in Korea

When this book was published in Korea as Yoko iyagi (요코 이야기, "Yoko's tale") in 2005, the sales were brisk partly due to a sales copy that said "why was this book banned in China and Japan?", but there was not much discernible social uproar about it.[5][6]

There had even been positive reviews written about it, accepting the book as delivering an anti-war and anti-colonial message.[7][8]

The situation completely changed in 2007, when it became a target of intense debate in Korea and in the United States. This development was triggered by the protests lodged by Korean-American students in the Greater Boston area in September, 2006.[9]

Response in Boston

The issue came to head after 2006, when 13 parents in a Greater Boston community urged the book be removed from the English curriculum of Dover-Sherborn Middle School, resulting in the convening of a schools committee which recommended a suspension of the book in November 2017.[10] The book was later reinstated at the school, to be used in a modified curriculum.[11]

The Boston Globe recapped the parents' position that they perceived the book as being "racist and sexually explicit". Both views were articulated by one parent in particular. The rape of Japanese refugee women by "Korean men" was disturbing, and he worried such a depiction could impart a stereotyped view on Korean men's treatment towards women to impressionable young minds.[lower-alpha 1][10] Broaching the subject of rape in the classrooms in this age group was inappropriate as well.[lower-alpha 2][10]

A Boston councilman[lower-alpha 3] also weighed in, stating that the Korean minority were being portrayed as the "bad guys", even though Japan was the one who had occupied Korea.[10] Given in narrative from the standpoint of the Japanese woman turned refugee at the end of World II, the book was felt as a distortion of the Korean experience under the colonial rule by Japan.[12]

The policies of the colonial rule that went unmentioned in the story included military draft and conscription of Koreans, as well as the killing and wounding of thousands of Koreans by the occupiers.[10]

Among staunch supporters of the book and author were teachers and parents, and they maintained that the book was an effective teaching tool and spoke out against censorship.[10] Even though vote was unanimous for suspending the book, the head of the panel acknowledged that the book could be taught in principle, if the issues could be addressed in the classroom, but they made the judgment call that the additional time made this impracticable.[10] And the ban was later revoked,[11] as already stated.

Other schools

Even prior to the Dover-Sherborn Middle School's decision to suspend the book, there have been other challenges tracked by The American Library Association,[10] some of which have been successful in removing the book from the curriculum and reading lists. Rye Country Day School in New York had acted swiftly by banning the book in September, 2006.[11]

One Catholic school and one private school, both in Massachusetts removed the book from their curricula in 2007.[11] A teacher at the latter[lower-alpha 4] wrote an opinion on the book which appeared in The English Journal.[13]

The school board of Montgomery County, Maryland struck the book off its recommended list in March, 2007.[14]

Author expresses contrition

The author said that she had no intention to disregard the history of Korea and apologized for any hard feelings felt by Korean readers. She stated her intention was to portray her childhood experiences in a softer way for young readers. She denied the accusations made by the Korean newspapers.[15][16]

Historical inaccuracies

The Korean media has characterized her book as "autobiographical fiction". It has believed there are several points of historical inaccuracies in her account. Certain "Korean historians" (unspecified) charge that some of her narrated incidents are imagined. However, the author insists she wrote her experience as she remembered it.[15]

U. S. bombers

Watkins gives in her book an account of sighting U. S. B-29 bombers (identified as that type by Mr. Enomoto). This has been characterized as suspect, since according to historians, there were no bombing in the area in July or August 1945. To which, the author retorted that she did not go so far as to say these airplanes bombarded her hometown of Nanam (Rannam).[15]

In fact, U.S. bombers were flying missions to the general area of Korea by this time, according to Yoshio Morita's book on evacuation from Korea: "From July 12 [1945] onward, American B-29's came almost every other day and regularly around 11:AM assaulting Rajin and Ungi in Northeast Korea, dropping many mines into the harbor".[lower-alpha 5][17]

An airplane attack on the train Yoko was aboard occurred, although she has not claimed she was able to identify the aircraft as American.[18] On this point, Korean media cast suspicion on this passage as anachronistic, since "American military did not bomb any part of North Korea during the time frame of the story".[19] The train was stalled by the attack 45 miles before reaching Seoul.[20]

Korean communist presence

Also, when pressed, she admitted she could not identify the armed uniformed militia that her family encountered as definitively "Korean Communists",[15] although that was the label she has given to her posing threat throughout the book.,[20] She explained that this had been the assumption she had made after hearing that the areas left behind in her trail had been overrun by communists. The book, in a different context,[lower-alpha 6] describes the mother telling Yoko that Koreans had formed what is known as an "Anti-Japanese Communist Army".[lower-alpha 7][21]

Harvard historian Carter Eckert had considered these points, and stated the only organized Korean "Communist Army" around this time would have been the guerrillas led by Soviet-trained Kim Il Sung, who "did not arrive in Korea until early September 1945", but there might have been "local Korean communist groups" present.[22]

Actually however, there was already a report that on August 8,[lower-alpha 8] a Korean contingent of 80 strong men was spotted with the Soviet Army, crossing the border into To-ri (土里; Japanese: Dori).[lower-alpha 9][23] It was only a short distance by speedboat across the Tumen River for them to arrive from Russia to this town.[23][lower-alpha 10]

"Korean Communist soldiers" were bereft of their uniforms for Yoko, her sister, and mother to use as disguise in the book.[lower-alpha 11][20] Some media coverage gave a forced reading saying this term can only have applicable meaning as soldiers of the "Korean People's Army", not established until 1948, so that Yoko was describing uniforms nonexistent at the time.[19]

Awards

Watkins was awarded the Literary Lights for Children Award by Associates of the Boston Public Library in 1998.[24] and also the Courage of Conscience Award by the Peace Abbey.[25][26]

See also

Explanatory notes

- Exact language in Kocian's piece in the Boston Globe: "..it will be the students' first exposure to Asian history"; and "You'll notice throughout the book these acts are committed by Korean men -- it is a pretty disturbing connotation of a group of people",... "The first impression you imprint in a child's mind is typically very hard to erase".

- He also criticized the teaching protocol for using this material without seeking parental consent.

- Sam Yoon. The Dover parents were not actually his constituents, as the Kiang & Tang (2009) study noted.

- Friends Academy, North Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

- Quote in Japanese:「[二十年]七月十二日以後、沖縄を基地とするアメリカのB29は、ほとんど隔日に、しかもきまって午後十一時ごろ、東北鮮の羅津、雄基に来襲し、そのつど多数の機雷を港内に投下していた。それ以前には"」

- In relation to the army eminent domaining some farmers' lands to expand its hospital.

- "Anti-Japanese Communist Army" (kōnichi kyōsangun, 抗日共産軍) has been used elsewhere to designate the China's People's Liberation Army. The Japanese of course would not dignify using Communist China's official name as the people's army.

- The day Russia formally declared war on Japan

- The group assaulted a police station in To-ri, and killed two Japanese officers.

- This town was about 60 miles north of Nanam, where Yoko lived.

- The locations is several nights' walk closer to Seoul than where their train derailed.

References

- Silvey, Anita (1995). Children's books and their creators. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-395-65380-7.

- `한국인 日소녀 강간` 美교재 국내 출간 (in Korean). 매경닷컴. 2007-01-17.

- 竹林はるか遠く―日本人少女ヨーコの戦争体験記 (in Japanese). ASIN 4892959219.

- ベストセラー [Best Sellers] (in Japanese). Amazon.co.jp. Archived from the original on 2013-06-07.

- Lee (H. K.) (2014), p. 38.

- Kim, Michael (December 2010). "The Lost Memories of Empire and the Korean Return from Manchuria, 1945-1950: Conceptualizing Manchuria in Modern Korean History" (PDF). Seoul Journal of Korean Studies. 23 (11): 195–223.

- Choi, Hyeon-mi (최현미) (2005-05-09). 日소녀가 본 日패망 풍경 : ‘요코 이야기’… 식민정책 비판 등 담아 [A Japanese girl's glimpse of defeated Japan: 'Yoko's Tale' includes criticism of colonial policy]. Munhwa Ilbo.

- Review in Yonhap News (March 3, 2005), cited by Kim (M.) (2010), p. 197, n5

- Lee (H. K.) (2014), p. 38–39.

- Kocian, Lisa (Nov 12, 2006). "Ban book from class, panel says". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22.

- Park Chung-a (Jan 23, 2007). "US: More American schools stop textbook falsifying Korea". Korea Times. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22.

- Kiang & Tang (2009), pp. 88–89.

- Walach, Stephen (January 2008), "So Far from the Bamboo Grove: Multiculturalism, Historical Context, and Close Reading" (PDF), The English Journal, 97 (3) JSTOR 30046824

- "Korean Americans Win Victory Over WWII Novel". Chosunilbo. March 19, 2007.

- "Controversial author stands by story of her war ordeal". JoongAng Daily. February 2, 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18.

- 왜곡 아니다 … 한국인에 상처준 건 죄송 (in Korean). JOINS. February 3, 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-09-09.

- Morita (1964), p. 28–29, possibly from cited source, Kitamura, Tomekichi/Ryūkichi, Razu dasshutsu no omoide 羅津脱出の思い出. Kitamura was buyun (府尹, 부윤) or city magistrate of Razu. (in Japanese)

- Watkins (1994), Chapter 2.

- "Korean Parents Angry over "Distorted" U.S. School Book". Chosunilbo. January 18, 2007.

- Watkins (1994), Chapter 3.

- Watkins (1994), p. 9.

- Eckert, Carter (December 16, 2006). "A Matter of Context". The Boston Globe. Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2009-09-10.

- Morita (1964), pp. 28–29.

- Brown, J. J. (September 20, 1998). "Library group to honor 5 children's-book authors at awards ceremony". The Boston Globe. p. 293. Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- "Literary Lights for Children". The Boston Public Library. Archived from the original on 2014-01-07.

- "Courage of Conscience Award Recipients". The Peace Abbey. Archived from the original on 2014-06-10.

Bibliography

- Kiang, Peter; Tang, Shirley (2009), Collet; Lien (eds.), "Transnational Dimensions of Community Empowerment: The Victories of Chanrithy Uong and Sam Yoon", The Transnational Politics of Asian Americans, Temple University Press, pp. 88–91, ISBN 9781592138623CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)pdf

- Lee, Hye Kyoung (李恵慶) (2014). "Tekusuto wo uragiru tekusuto: Takebayashi haruka tōku ni okeru sensō no kioku to kioku no sensō" テクストを裏切るテクスト―『sensō 』における戦争の記憶と記憶の戦争 [Memory, Nostalgia and Nationalism: Unlocking The Textual Unconscious in Yoko Kawashima Watkins's So Far From The Bamboo Grove] (PDF). Asia-Pacific Review アジア太平洋レビュー (in Japanese) (11): 38–52. (published by the Osaka University of Economics and Law)

- Morita, Yoshio (森田芳夫) (1964). Chōsen shūsen no kiroku: Bei So ryōgun to nihonjin no hikiage 朝鮮終戦の記錄: 米ソ両軍の進駐と日本人の引揚 (in Japanese). Gannando.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watkins, Yoko Kawashima (1994) [1986]. So Far from the Bamboo Grove. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-6881-3115-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)