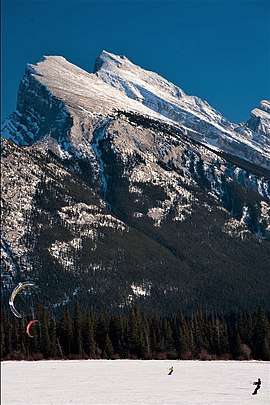

Snowkiting

Snowkiting or kite skiing is an outdoor winter sport where people use kite power to glide on snow or ice. The skier uses a kite to give them power over large jumps. The sport is similar to water-based kiteboarding, but with the footwear used in snowboarding or skiing. The principles of using the kite are the same, but in different terrain. In the early days of snowkiting, foil kites were the most common type; nowadays many kiteboarders use inflatable kites. However, since 2013, newly developed racing foil kites seem to dominate speed races and expedition races, like Red Bull Ragnarok (held on the Norwegian Hardangervidda plateau) and the Vake mini-expedition race (held at Norway's most northern Varanger peninsula). Snowkiting differs from other alpine sports in that it is possible for the snowkiter to travel uphill and downhill with any wind direction. Like kiteboarding, snowkiting can be very hazardous and should be learned and practiced with care. Snowkiting is becoming increasingly popular in places often associated with skiing and snowboarding, such as Russia, Canada, Iceland, France, Switzerland, Austria, Norway, Sweden and the Northern and Central United States. The sport is becoming more diverse as adventurers use kites to travel great distances and sports enthusiasts push the boundaries of freestyle, big air, speed and back country exploration.

History

20th century

As a child Dieter Strasilla, inspired by Otto Lilienthal, practiced gliding around Berchtesgaden and in the 1960s he began parapente experiments (also with his brother Udo in USA) in Germany and Switzerland, parachute-skiing in 1972 and later perfected a kiteskiing system using self-made paragliders and a ball-socket swivel allowing the pilot to kitesail upwind or uphill, but also to take off into the air at will, swivelling the body around to face the right way.[1]

Kiteskiers began kiteskiing on many frozen lakes and fields in the US midwest and east coast. Lee Sedgwick and a group of kiteskiers in Erie, PA were early ice/snow kiteskiers. In 1982 Wolf Beringer started developing his shortline Parawing system for skiing and sailing. This was used by several polar expeditions to kite-ski with sleds, sometimes covering large distances.[2] Ted Dougherty began manufacturing 'foils' for kiteskiing and Steve Shapson of Force 10 Foils also began manufacturing 'foils' using two handles to easily control the kite. In the mid-1980s Shapson, while icesailing, took out an old two line kite and tried to ski upwind on a local frozen lake in Wisconsin. Shapson demonstrated the sport of 'kiteskiing' in Poland, Germany, Switzerland and Finland. He also used grass skis to kiteski on grassy fields. Early European kiteskiers were Keith Stewart and Theo Schmidt, who also were among the first to waterski with kites. American Cory Roeseler together with his father William developed a Kiteski system for waterskiing and began winning in windsurf races featuring high following winds, such as in the gorge of the Columbia river. The following terms describe the sport of 'Traction Kiting' or some refer to as 'Power Kiting': Kite buggying, kite skiing, kitesurfing and kite landboarding.

In the mid-1980s e.g. some alpine skiers used a rebridled square parachute to ski upwind on a frozen bay in Erie, PA. In the late 1990s small groups of French and North American riders started pushing the boundaries of modern freestyle snowkiting. The Semnoz crew from France began hosting events at the Col du Lautaret and other European sites where the mountainous terrain lent itself to "paragliding" down the hills. In North America, riders were mainly riding snow-covered lakes and fields where tricks were being done on the flat ground, jumps, rails and sliders.

21st century

The 2000s have seen a giant leap forward in snowkite-specific technologies, skill levels and participants in every possible snow-covered country. The development of snowkite specific, de-powerable, foil kites have allowed snowkiters to explore further and push the limits of windpowered expeditions. Recent crossings in record times of large snowfields and even Greenland have been accomplished through the use of snowkites.

On the forefront of extreme freestyle snowkiting, dedicated snowkiting communities from Utah to Norway are pushing the freestyle envelope and documenting their efforts through films like Something Stronger and Dimensions,[3] and Snowkite Magazine[4] which is available as a digital magazine. The extreme envelope of snowkiting freestyle and back country is being pushed by Chasta, a French kiter sponsored by Ozone Kites[5] now based in New Zealand.

Better equipment, safety practices, community know-how and qualified instructors are readily available in many areas, allowing people to learn properly and safely through different means than trial and error. The sport is currently being enjoyed by kiters of all ages and in a wide variety of activities ranging from mellow jaunts on a lake, to kitercross events, from multi-day expeditions, to flying off mountains, from freestyle jib tricks, to huge cliff jumps as well as endurance and course racing.

On 20 January 2007, during the Antarctic summer, Team N2i became the first people to reach the Antarctic pole of inaccessibility without powered aid, using kite skiing as their primary means of propulsion.[6]

There is a small segment of kiters that participate in GPS speed competitions where kiters record speed data on a GPS unit and submit it to a coordinating body for comparison to other kiter's speeds. In the Stormboarding[7] world wide speed ranking Joe Levins, an American kiter, was the first to reach 70 mph/112 km/h in 2008. In 2009 Christopher Krug, an American kiter sponsored by Peter Lynn Kiteboarding[8] pushed the envelope further to a speed of 73.5 mph/118 km/h.

On 5 June 2010, Canadian Eric McNair-Landry and American-French Sebastian Copeland kite-skied 595 kilometres (370 mi) in 24 hours to set a distance world record.[9] The team completed the first partial east to west crossing of Antarctica using kites, a distance of over 4,000 kilometers via Pole of Inaccessibility research station and the South Pole over 82 days in 2011–12.[10]

Technique and Ride

Snowkiting is very similar to windsurfing in technique. It is harder to maintain balance than with basic snowboarding, since the hands and arms have to control the kite and thus are not completely available for balance. However, the balance issue can be somewhat offset by the up-and-forward force generated by the kite.

With previous snowboard models, it was necessary to minimize side cuts to avoid inadvertently riding upwind. This happens because in leaning back to be a counterweight against the force of the kite, the heels of the snowkiter naturally dig into the snow, causing the board to turn upwind. Modern reverse camber snowboards have addressed this problem.

There are specialized equipment for snowkiting.[11] They have a radius of 100-150m, skis for snowkiting are 215cm long, snowkiteboards have a length of 200cm. Rotational snowboard bindings that go between the board and traditional boot binding are becoming popular among snow kiters. The rotational binding relieves stress in the ankles and knees often associated with snowkiting.

Terrain

Kite Boarding is practical on very many areas, as long as there is a significant amount of wind to keep the kite up. It is not always used on slopes, and can in fact be used with no slope, or even an upwards slope, as long as there is enough wind to offset the drag incurred. It can prove more difficult to have any riding time when you go on a steeper slope, as the wind can be blocked and or become turbulent passing over the peak of the hill, causing the kite to behave erratically and even fall or be pushed to the ground.

See also

References

- Skywing

- Wolf Behringer, Parawings ISBN 3-88180-091-3, 1996

- SnowkiteFilm.com

- Drift Snowkite Magazine Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Ozone Kites

- "UK team makes polar trek history", BBC news story, retrieved June 2007

- Stormboarding

- Peter Lynn Kiteboarding

- Greenland ski wrap-up: New kite world record

- Polar News ExplorersWeb - ExWeb interview Sebastian Copeland and Eric McNair-Landry (part 2/2): An odd encounter in a paralleled universe

- CustomSkis.ru - Specially skis and snowboards for snowkiting

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Snowkiting. |

- KiteTeam.ru/en - Snowkiting Guide

- www.wissa.org - World Ice and Snow Sailing Association

- Competition Snowkiting Masters 2013 video

- kiteboarding.cz - Snowkiting in the Czech Republic

- Funkitesurf.com - Snowkiting Spanish forum