Snow-Bound

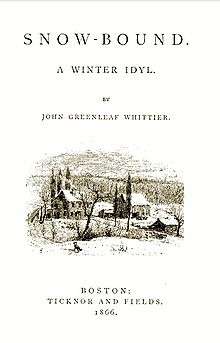

Snow-Bound: A Winter Idyl is a long narrative poem by American poet John Greenleaf Whittier first published in 1866. The poem, presented as a series of stories told by a family amid a snowstorm, was extremely successful and popular in its time. The poem depicts a peaceful return to idealistic domesticity and rural life after the American Civil War.

Overview

The poem takes place in Whittier's childhood home, today known as the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead, which still stands in Haverhill, Massachusetts.[1] The poem chronicles a rural New England family as a snowstorm rages outside for three days. Stuck in their home for that period, the family members exchange stories by their roaring fire.

In a later edition's introduction, Whittier notes that the characters are based on his father, mother, brother, two sisters, an unmarried aunt and unmarried uncle, and the district schoolmaster who boarded at the homestead. The final guest in the poem was based on Harriet Livermore. The poem includes an epigraph quoting several lines from "The Snow-Storm" by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The story begins on a sunless, bitterly cold day in December in an unnamed year, though the narrator elsewhere notes that many years have passed since the events of this storm, and that only he and his brother remain living.. The family completes their chores for the day when the storm comes with the evening. Snow falls for the entire night and leaves an unrecognizable landscape in the morning. At the request of the father, the boys dig a path towards the barn to care for the livestock. They notice no sounds, even from the nearby brook or church-bells ringing. As the day again turns to night, the family starts a fire and, shut in because of the snow, they gather around the hearth.

The father tells of his experiences eating, hunting, and fishing with Native Americans and others near Lake Memphremagog in Vermont, Great Marsh in Salisbury, Massachusetts, the Isles of Shoals, and elsewhere. The mother, while continuing her domestic chores, tells the family's connection to the Cocheco Massacre, about her rural childhood and carousing in nature, and how Quaker families look to inspiration from certain writers.

Next, the uncle, who is not formally educated, tells of his knowledge of nature, like how clouds can tell the future and how to hear meaning in the sounds of birds and animals. He is compared to Apollonius of Tyana and Hermes. The kindly unmarried aunt tells of her own happy life. The elder sister is introduced, though she does not tell a story, and the narrator fondly recalls a younger sister who died the year before. The schoolmaster, son of a poor man who took odd jobs to become independent, sings and tells of his time at Dartmouth College. The narrator also describes a "not unfeared, half-welcome guest" who rebukes the group when they show a lack of culture. Eventually, the fire goes out and the various characters go to bed for the night.

In the morning, they see that the highways and roads are being cleared. The workers exchange jokes and ciders with the elders of the family while the children play in the snow. The local doctor stops by to inform the mother that her help is needed for someone who is sick. A week goes by since the storm and the family re-reads their books, including poetry and "one harmless novel", before the local paper is finally delivered, which allows them to read and think about warmer places.

Publication history and response

Whittier began the poem originally as a personal gift to his niece Elizabeth as a method of remembering the family.[2] Nevertheless, he told publisher James Thomas Fields about it, referring to it as "a homely picture of old New England homes".[2] The poem was written in Whittier's home in Amesbury, Massachusetts,[3] though it is set at his ancestral home in Haverhill.[4] Snow-Bound was first published as a book-length poem on February 17, 1866.[5] The book, which cost an expensive $1.25 at the time, was elaborately illustrated. As publisher Fields noted, "We have expended a large sum of money on the drawings and engravings... But we meant to make a handsome book whether we get our money back or not."[6]

Snow-Bound was financially successful, much to Whittier's surprise.[7] On its first day of release, the poem sold 7,000 copies.[6] By the summer after its first publication, sales had reached 20,000, earning Whittier royalties of ten cents per copy. He ultimately collected $10,000 for it.[8] As early as 1870, the poem was recognized as the crucial work which changed Whittier's career and ensured a lasting reputation.[6] Whittier was deluged with letters from fans and even visitors to his home. He tried to respond to his fan mail but noted by 1882 that for each one he answered "two more come by the next mail".[9]

The book's popularity also led to the home depicted in the poem being preserved as a museum in 1892.[10]

The first important critical response to Snow-Bound came from James Russell Lowell. Published in the North American Review, the review emphasized the poem as a record of a vanishing era. "It describes scenes and manners which the rapid changes of our national habits will soon have made as remote from us as if they were foreign or ancient," he wrote. "Already are the railroads displacing the companionable cheer of crackling walnut with the dogged self-complacency and sullen virtue of anthracite."[11] An anonymous reviewer in the Monthly Religious Magazine in March 1866 predicted the poem "will probably be read at every fireside in New England, reread, and got by heart, by all classes, from old men to little children, for a century to come".[12] In its period, the poem was second in popularity only to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The Song of Hiawatha and was published well into the twentieth century. Though it remains in many common anthologies today, it is not as widely read as it once was.[10]

Analysis

The poem attempts to make the ideal past retrievable.[13] By the time it was published, homes like the Whittier family homestead were examples of the fading rural past of the United States.[10] The use of storytelling by the fireplace was a metaphor against modernity in a post-Civil War United States, without acknowledging any of the specific forces modernizing the country.[14] The raging snowstorm also suggests impending death, which is combated against through the family's nostalgic memories.[15] Scholar Angela Sorby suggests the poem focuses on whiteness and its definition, ultimately signaling a vision of a biracial America after the Civil War.[16]

References

- Corbett, William. Literary New England: A History and Guide. Boston: Faber and Faber, 1993: 126. ISBN 0-571-19816-3

- Woodwell, Roland H. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Biography. Haverhill, Massachusetts: Trustees of the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead, 1985: 336.

- Danilov, Victor J. Famous Americans: A Directory of Museums, Historic Sites, and Memorials. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2013: 202. ISBN 978-0-8108-9185-2

- Corbett, William. Literary New England: A History and Guide. Boston: Faber and Faber, 1993: 126. ISBN 0-571-19816-3

- Woodwell, Roland H. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Biography. Haverhill, Massachusetts: Trustees of the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead, 1985: 337.

- Cohen, Michael C. The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015: 188. ISBN 978-0-8122-4708-4

- Wagenknecht, Edward. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Portrait in Paradox. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967: 7.

- Woodwell, Roland H. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Biography. Haverhill, Massachusetts: Trustees of the John Greenleaf Whittier Homestead, 1985: 338–339.

- Irmscher, Christoph. Public Poet, Private Man: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow at 200. University of Massachusetts Press, 2009: 131. ISBN 9781558495845.

- Sorby, Angela. Schoolroom Poets: Childhood, Performance, and the Place of American Poetry, 1865–1917. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2005: 35. ISBN 1-58465-458-9

- Sorby, Angela. Schoolroom Poets: Childhood, Performance, and the Place of American Poetry, 1865–1917. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2005: 37. ISBN 1-58465-458-9

- Cohen, Michael C. The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015: 261. ISBN 978-0-8122-4708-4

- Buell, Lawrence. New England Literary Culture: From Revolution Through Renaissance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986: 127. ISBN 0-521-37801-X

- Newcomb, John Timberman. Would Poetry Disappear?: American Verse and the Crisis of Modernity. Ohio State University Press, 2004: 39–40. ISBN 978-0-8142-5124-9

- Newcomb, John Timberman. Would Poetry Disappear?: American Verse and the Crisis of Modernity. Ohio State University Press, 2004: 41. ISBN 978-0-8142-5124-9

- Sorby, Angela. Schoolroom Poets: Childhood, Performance, and the Place of American Poetry, 1865–1917. Durham, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2005: 36. ISBN 1-58465-458-9

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- "Snowbound: A Winter Idyl" at the Poetry Foundation

- "Snow-Bound" at John Greenleaf Whittier: Essex County's Native Son, hosted by North Shore Community College