Site Two Refugee Camp

Site Two Refugee Camp (also known as Site II or Site 2) was the largest refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border and, for several years, the largest refugee camp in Southeast Asia. The camp was established in January 1985 during the 1984-1985 Vietnamese dry-season offensive against guerrilla forces opposing Vietnam's occupation of Cambodia.[1]

Site Two | |

|---|---|

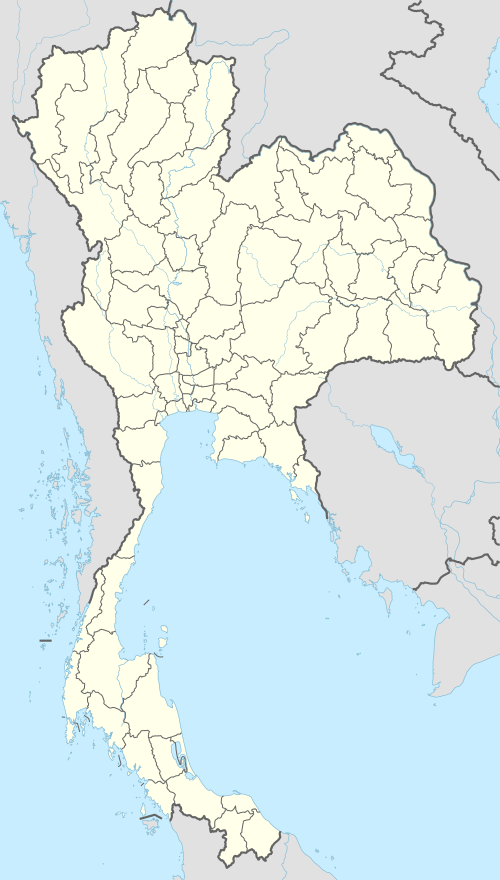

Site Two Location in Thailand | |

| Coordinates: 14°04′59″N 102°54′55″E | |

| Country | |

| Opened by the Royal Thai Government | January, 1985 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.5 km2 (2.9 sq mi) |

| Population (1989) | |

| • Total | 198,000 |

| • Density | 26,400/km2 (68,000/sq mi) |

Site Two was closed in mid-1993 and the great majority of its population was voluntarily returned to Cambodia.[2]

Camp construction

In January 1985 the Royal Thai Government, together with the United Nations Border Relief Operation (UNBRO) and other UN agencies, decided to resettle populations displaced from refugee camps that had been destroyed by military activity into a single camp where aid agencies could provide combined services.[3] Site Two was located in Thailand 70 kilometers northeast of Aranyaprathet, near Ta Phraya, approximately 4 kilometers from the Cambodian border.

Camp population

The camp covered 7.5 square kilometres (2.9 sq mi) and combined the populations of Nong Samet (Rithysen), Bang Poo (Bang Phu), Nong Chan, Nam Yeun (a camp located on the eastern Thai-Cambodian border, near Laos[4]), Sanro (Sanro Changan), O'Bok, Ban Sangae (Ampil), and Dang Rek (Dong Ruk) camps,[3]:88 all of which had been displaced by fighting between November 1984 and March 1985. These camps supported the non-communist resistance spearheaded by Son Sann's Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF).[5] However, Site Two was intended as a civilian camp and the Khmer People's National Liberation Armed Forces (KPNLAF) were based in other locations.[6]

One section of the camp was reserved for Vietnamese refugees and beginning in January 1988 Thailand transferred Vietnamese boat people directly to Site Two.[7][8]

Between 1989 and 1991 the camp's population went from 145,000 to over 198,000.[9]

Camp services

Initially programs at Site Two were limited to the most basic support services: medical care, public health programs, sanitation, construction, and skills training in areas directly related to the running of the camp. This was in keeping with the Thai policy of "humane deterrence": the principle that the camps should not become permanent settlements or provide a level of assistance beyond what the refugees could expect to find in Cambodia.[3]:100

Camp services were mostly provided by the American Refugee Committee (ARC), Catholic Office for Emergency Relief and Refugees (COERR), Concern, Christian Outreach (COR), Handicap International, the International Rescue Committee, Catholic Relief Services (CRS), the Japan International Volunteer Center (JVC), Malteser-Hilfsdienst Auslandsdienst (MHD), Médecins Sans Frontières, Operation Handicap International (OHI), the International Rescue Committee (IRC), Japan Sotoshu Relief Committee (JSRC), and YWAM.[10] These organizations were coordinated by UNBRO, which was directly responsible for the distribution of food and water.[10]

Food and water

On a per person basis rice, canned or dried fish, one egg and a vegetable were distributed weekly at Site Two; dried beans, oil, salt, and wheat flour were given once a month.[11] Exact amounts for the weekly and monthly rations in 1990 were as follows:

- Rice: 3.4 kilograms/week

- Eggs: 100 grams/week

- Vegetables: 500 grams/week

- Fish products: 210 grams/week

- Dry beans: 500 grams/month

- Oil: 700 grams/month

- Salt: 280 grams/month

- Wheat flour: 700 grams/month[3]:134–140

Water was a particular problem at Site Two. UNBRO constructed a large reservoir at Ban Wattana, approximately 12 kilometers from the camp. Most of Site Two's water was trucked in from this reservoir but in the dry season even this source was insufficient for the camp's needs. Late in 1990, UNBRO began drilling several deep wells in the camp, which ultimately provided much of the camp's water.[3]:96

Health services

Medical services were provided by 5 dirt-floored, thatched bamboo hospitals and 8 outpatient clinics staffed by doctors and nurses from international voluntary agencies as well as Khmer medics and nurses. There was no surgical facility and surgical emergencies were referred to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) hospital at Khao-I-Dang,[12] although family members of KPNLAF soldiers could obtain medical and surgical care at the Chiang Daoy Military Hospital, just outside the camp on the northern perimeter.[3]:75

Education

Education at Site Two progressed slowly due to the Thai Government's policy of "humane deterrence" which discouraged programs and services that would attract refugees from Kampuchea. In 1988, with the agreement of the Royal Thai Government, UNBRO launched a major new educational assistance program, focusing at the primary level and providing support for curriculum development, the printing of educational materials, teacher training and the training of teacher trainers, the provision of supplies and the construction and equipment of classrooms.

By early 1989 the school system consisted of some fifty primary schools with an enrollment of approximately 70,000 pupils; three middle schools (collèges) and three high schools (lycées) with approximately 7,000 students, and more than 10,000 adults in literacy and vocational skills programs. Instruction was provided in Khmer by some 1,300 primary and over 300 secondary teachers recruited almost entirely from within the camps.[13]

Security

The Khmer Police took care of traditional police functions within Site Two. Until 1987 overall camp security was the responsibility of a special Thai Rangers unit known as Task Force 80, however this unit violated human rights extensively[14][15][16] until it was disbanded in April 1988[17] and replaced by the DPPU (the Displaced Persons Protection Unit), a specially trained paramilitary unit created in 1988 expressly to provide security on the Thai-Cambodian border. The DPPU was responsible for protecting camp boundaries and preventing bandits from entering the camp.[3]:104

Camp closing

Site Two was closed in mid-1993 and the great majority of its population was voluntarily repatriated to Cambodia.[18]

References

- Robinson C. Terms of refuge: The Indochinese Exodus and the International Response. London ; New York, New York: Zed Books; Distributed in the USA exclusively by St. Martin's Press, 1998, p. 92.

- Grant M, Grant T, Fortune G, Horgan B. Bamboo & Barbed Wire: Eight Years as a Volunteer in a Refugee Camp. Mandurah, W.A.: DB Pub., 2000.

- French LC. Enduring Holocaust, Surviving History: Displaced Cambodians on the Thai-Cambodian Border, 1989-1991. Harvard University, 1994.

- Lynch, James F. Border Khmer: A Demographic Study of the Residents of Site II, Site B,and Site 8. The Ford Foundation, 1989.

- Normand, Roger, "Inside Site 2," Journal of Refugee Studies, 1990;3:2:156-162, p. 158.

- Reynell J. Political Pawns: Refugees on the Thai-Kampuchean Border. Oxford: Refugee Studies Programme, 1989.

- Robinson, p. 96.

- Vietnamese Refugee Camps at Thailand-Cambodia border

- "Site II Demographic Survey,"

- "Services at Site II,"

- Reynell, J., "Socio-economic Evaluation of the Khmer camps on the Thai/Kampuchean Border," Oxford University Refugee Studies Programme. Report Commissioned by World Food Programme, Rome, 1986.

- Soffer, Allen and Wilde, Henry, "Medicine in Cambodian Refugee Camps," Annals of Internal Medicine, 1986;105:618-621, p. 619.

- Gyallay-Pap, Peter, "Reclaiming a Shattered Past: Education for the Displaced Khmer in Thailand," Journal of Refugee Studies, 1989;2:2:257-275, p. 266.

- Abrams F, Orentlicher D, Heder SR. Kampuchea: After the Worst: A Report on Current Violations of Human Rights. New York: Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1985. ISBN 0-934143-29-3

- Lawyers Committee for Human Rights (U.S.). Seeking Shelter: Cambodians in Thailand: A Report on Human Rights. New York: Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1987. ISBN 0-934143-14-5

- Al Santoli, Eisenstein LJ, Rubenstein R, Helton AC, Refuge Denied: Problems in the Protection of Vietnamese and Cambodians in Thailand and the Admission of Indochinese Refugees into the United States. New York: Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, No.: ISBN 0-934143-20-X, 1989.

- New York Times, "Thailand to Phase Out Unit Accused of Abusing Refugees," April 7, 1988.

- Grant M, Grant T, Fortune G, Horgan B. Bamboo & Barbed Wire: Eight Years as a Volunteer in a Refugee Camp. Mandurah, W.A.: DB Pub., 2000.

External links

- French Lindsay Cole, Mam B, Wuthy T, Grant T, Veasna M. Displaced Lives: Stories of Life and Culture from the Khmer in Site II, Thailand. International Rescue Committee, 1980.

- French, Lindsay Cole. Enduring Holocaust, Surviving History: Displaced Cambodians on the Thai-Cambodian Border, 1989-1991. Harvard University, 1994

- Thai-Cambodian Border Camps: Site Two

- Braile, L. E. (2005). We Shared the Peeled Orange: the letters of "Papa Louis" from the Thai-Cambodian Border Refugee Camps, 1981-1993. Saint Paul, Syren Book Co.

- Vietnamese Refugees at Site II

- Tim Grant's Site Two Photo Album

- More of Tim Grant's Site Two Photos at Flickr