Sir David Lindsay, 4th Baronet

Sir David Lindsay, 4th Baronet (c. 1732 – 6 March 1797) was a Scottish-born soldier in the British Army. One of the Lindsay of Evelix family, he succeeded to the baronetcy upon the death of his father, Sir Alexander Lindsay, in 1762.

Sir David Lindsay Bart. | |

|---|---|

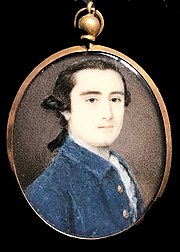

Painting of Lindsay by Sir Joshua Reynolds | |

| Born | c. 1732 |

| Died | 6 March 1797 (aged 64–65) Cavendish Square, London |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1758–1779 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | 3rd Foot Guards |

| Commands held | 59th Foot (1776–77) |

| Battles/wars | Anglo-French War (1778–1783) |

He began his career in the 3rd Foot Guards; in 1776, he became colonel of the 59th Foot, then major-general in 1778. Promoted lieutenant-general in 1779, during the Anglo-French War (1778–1783), he commanded the defences of Plymouth at the time of the Franco-Spanish Armada.

He resigned his position in early 1780, which ended his active service, his promotion to General in 1796 being a function of time served. He died in Cavendish Square, London, on 6 March 1797.

Early life

David Lindsay was born circa 1732 to Sir Alexander Lindsay, the third of the Lindsay of Evelix baronets of Scotland, and Amelia née Murray.[1][2] In 1752 he cut off ties with his sister, Margaret Lindsay after she eloped with the painter Allan Ramsay, whom the Lindsays considered socially inferior. Because of the feud David Lindsay deliberately patronised Ramsay's rival Sir Joshua Reynolds. Lindsay was only reconciled with Margaret after the death of their father on 6 May 1762, after which David became the fourth baronet Evelick.[2][1]

Military career

Lindsay served as Custos Brevium of the Court of King's Bench and from 1758 to 1776 was captain of a company of the 3rd Regiment of Foot Guards, a traditionally Scottish unit.[1] As was the tradition, he continued to receive advancement in army rank, though he remained nominally a guards captain, and on 30 January 1776, he was appointed colonel of the 59th Foot.[3] Previously stationed in Boston, Massachusetts, the 59th suffered heavy losses when the American War of Independence began. The survivors were posted to other units, and its officers returned to England in 1776 to reform the regiment.[4]

On 6 September 1777, Lindsay was promoted major-general, shortly before the Anglo-French War began in June 1778. In October 1778, he was commanding troops based at Warley, established as a safeguard against French invasion, when the camp was inspected by George III.[5][6]

Appointed lieutenant-general on 27 February 1779, on 29 May he was given command of Plymouth during a possible invasion associated with the Armada of 1779.[7][8] He seems to have viewed the appointment with some despair and remained in London for a month, attempting to secure a meeting with Lord Amherst, commander-in-chief of the forces.[9] Upon arriving in Plymouth, Lindsay lamented his lack of troops and lack of co-operation from the Board of Ordnance; although Amherst sympathised, he noted troops were thinly stretched across the entire coastline.[10]

Lindsay sought to find volunteers for the defence of the city and, following a public subscription that raised £1,000 for the purpose, issued 2,520 stands of arms to volunteers by 25 August – and noted that he had 20,000 men standing by. Lindsay feared being made a scapegoat for the chaotic defensive measures, and frequently requested more men, while claiming the efforts he expended made him ill with fatigue.[11] Later in the year Lindsay wrote that he believed he had brought about a significant improvement in defences and had the support of the distinguished general Charles Grey in the matter, but by 2 September had offered his resignation.[12]

The Armada was badly affected by sickness, and returned to port in September, ending the possibility of invasion that year. In November John Robinson, the secretary to the Treasury, feared a parliamentary enquiry into defensive preparations against the Armada would call Lindsay to testify, who would reveal the unpreparedness of Plymouth for defence, and possibly cause the downfall of Lord North's government.[13] The administration successfully blocked demands for an enquiry in November, and again the following April; during the debates, it was noted Lindsay had since resigned his appointment.[14]

This seems to have ended his active service, although he remained colonel of the 59th until his death; he was promoted general on 14 May 1796, a function of time served.[15]

Personal life

Lindsay was married to Susannah-Charlotte Long. They had six children, of which two, John and Susan, died in infancy. Their son William became ambassador to Venice and governor of Tobago but died before his father; another son, Charles became a naval officer. One daughter, Charlotte-Amelia, married the politician Thomas Steele and the other, Elizabeth, married Augustus Schultz.[1]

Lindsay died on 6 March 1797 and the baronetcy was inherited by Charles but, being childless, it became extinct upon his death by drowning in 1799.[1] The Evelick estate was inherited by Charlotte-Amelia.[16]

References

- Burke, John; Burke, Bernard (1844). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Extinct and Dormant Baronetcies of England, Ireland, and Scotland. W. Clowes. p. 630.

- "Sir David Lindsay, 4th Bart of Evelick (about 1732 – 1797)". National Galleries of Scotland. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "No. 11635". The London Gazette. 27 January 1776. p. 2.

- Watson n.d.

- "No. 11802". The London Gazette. 2 September 1777. p. 2.

- "No. 11920". The London Gazette. 20 October 1778. p. 1.

- "No. 11956". The London Gazette. 23 February 1779. p. 2.

- "No. 11983". The London Gazette. 29 May 1779. p. 2.

- Patterson 1960, p. 142.

- Patterson 1960, p. 147.

- Patterson 1960, p. 185.

- Patterson 1960, pp. 191–192.

- Patterson 1960, p. 218.

- Patterson 1960, p. 224.

- "No. 13892". The London Gazette. 14 May 1796. p. 459.

- Jervise, Andrew (1853). The History and Traditions of the Land of the Lindsays in Angus and Mearns, with Notices of Alyth and Meigle. Sutherland & Knox. p. 302.

Sources

- Burke, John; Burke, Bernard (1844). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Extinct and Dormant Baronetcies of England, Ireland, and Scotland. W. Clowes.

- Jervise, Andrew (1853). The History and Traditions of the Land of the Lindsays in Angus and Mearns, with Notices of Alyth and Meigle. Sutherland & Knox.

- Patterson, Alfred Temple (1960). The Other Armada: The Franco-Spanish Attempt to Invade Britain in 1779. Manchester University Press.

- Watson, Graham (n.d.). "59th Foot". Land forces of Britain, the Empire and Commonwealth. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Sir David Lindsay, 4th Bart of Evelick (about 1732 – 1797)". National Galleries of Scotland. Retrieved 13 June 2020.