Sioux Quartzite

The Sioux Quartzite is a Proterozoic quartzite that is found in the region around the intersection of Minnesota, South Dakota, and Iowa, and correlates with other rock units throughout the upper midwestern and southwestern United States. It was formed by braided river deposits, and its correlative units are thought to possibly define a large sedimentary wedge that once covered the passive margin on the then-southern side of the North American craton. In human history, it provided the catlinite, or pipestone, that was used by the Plains Indians to carve ceremonial pipes. With the arrival of Europeans, it was heavily quarried for building stone, and was used in many prominent structures in Sioux Falls, South Dakota and shipped to construction sites around the Midwest. Sioux Quartzite has been and continues to be quarried in Jasper, Minnesota at the Jasper Stone Company and Quarry, which itself was posted to the National Register of Historic Places on January 5, 1978.[1] Jasper, Minnesota contains many turn-of-the-century quartzite buildings, including the school, churches and several other public and private structures, mostly abandoned.

Geology

The Sioux Quartzite is a red to pink Proterozoic quartzite. It is a thick stratigraphic unit (~3000 m[2]) that crops out in southwestern Minnesota, southeastern and south-central South Dakota, northwestern Iowa, and a small part of northeastern Nebraska. It is correlated with other sandstone and quartzite units across Wisconsin (at Rib Mountain, Baraboo, Barron, Waterloo, and Flambeau), southeastern Iowa, southern Nebraska, and north-central New Mexico and southeast-central Arizona (Ortega, Mazatzal, and Deadman Quartzite).[3]

Its age is constrained to be between 2280 ± 110 Ma[4] from the uranium-lead dating of a rhyolite that underlies it in northwestern Iowa, and 1120 Ma[5] from a potassium-argon date of deformation of the Sioux Quartzite in Pipestone, Minnesota. Its age can be better-constrained by extrapolation correlative units to between 1760 ± 10 Ma.[6] and 1640 ± 40 Ma[7] This period in which the Sioux Quartzite and its correlative units were deposited is known as the Baraboo interval, in which high relative sea levels covered a large amount of North America.[8]

The Sioux quartzite was primarily formed by braided river deposits, of quartz arenite composition, with 95% of the rock being composed of rounded, fine to medium (0.125–0.5 mm) sand-size quartz grains.[3] The rivers are believed to flow southeast, at a relatively shallow gradient.[3] Its basal conglomerate is thought to be braided stream deposits that are more proximal to the source, and there is possible marine influence on the upper part of the unit – this interpretation is supported by evidence of marine sediments (shales and banded iron formations) atop its correlative unit in Baraboo, Wisconsin.[9] In addition, the unit contains ~1 meter beds of claystone, which are known as catlinite or pipestone, because these beds were used by the natives of the area to carve pipe bowls.[3] It is thought that the Sioux Quartzite and its correlative units are parts of a once-laterally-extensive sedimentary wedge that covered the then-southern passive margin of the North American craton.[8]

The Sioux Quartzite is extremely resistant to erosion, and has formed a topographic high through most of Phanerozoic time. It was inundated by Phanerozoic seas during the periods of maximum sea level, and subsequent erosion removed these sedimentary units. For this reason, the only geologic units to sit atop the Sioux Quartzite are of Cretaceous age, deposited when a large portion of North America was covered by the Cretaceous Interior Seaway.

Many present-day outcrops of Sioux Quartzite were exposed by glacial erosion during the Quaternary.[3] Some of these have been dated with the cosmogenic radionuclides beryllium-10 and aluminium-26 to determine how long ago the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated from the Upper Midwest. These dates show that southwestern Minnesota was last covered in glacial ice at least 500,000 years ago.[10]

Use in buildings

Several mansions and other notable buildings have been built using Sioux Quartzite. These include:

- George W. and Nancy B. Van Dusen House Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1888, 12,000 ft2, National Register of Historic Places 1995

- David Whitney House, Detroit, Michigan, 1894, 21,000 ft2, National Register of Historic Places 1972

- John Pierce House, Sioux City Iowa, 1893, 23 rooms, National Register of Historic Places

- Fowler Methodist Episcopal Church, Minneapolis[11]

- John Rowe House, Jasper, Minnesota, 1903, National Register of Historic Places 1980

John Rowe House, Minnesota

John Rowe House, Minnesota - Jasper High School, Jasper, Minnesota, 1911 (main building) 1939 (Auditorium and Gymnasium) 1957 (agriculture and band room addition) [12]

- Bauman Hall, Jasper, Minnesota, constructed in 1891, National Register of Historic Places, 1979 [13]

- Hattie Phillips House, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 1885, razed 1966, however foundation reused[14]

- Pipestone City Hall, Pipestone, Minnesota, 1896 now the Pipestone County Museum

- 1884 Syndicate Block, shop buildings in Pipestone, Minnesota

- The Calumet Inn, Pipestone, Minnesota

- Several buildings at the South Dakota School for the Deaf - high school (1885 / 1912), administration (1883), gym (1900 / 1929 / 1938), and other buildings / additions since razed

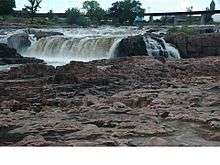

- Queen Bee Mill in Falls Park

- Old Sioux Falls Light & Power hydro plant in Falls Park

- South Dakota State Penitentiary, Sioux Falls SD, 1881

- The Pipestone County Courthouse, Pipestone, Minnesota, 1902

- Pipestone Carnegie library, Pipestone, Minnesota, 1904

- St. Mary's Catholic Church, Salem, South Dakota

- Rock County Courthouse and Veterans Memorial, Luverne, Minnesota 1888

- Rose Stone Inn, Dell Rapids, South Dakota, 1908

- The Odd Fellows Home of Dell Rapids, Dell Rapids, South Dakota, 1910 National Register of Historic Places 2012

- Old Central School opened its door in 1879, which was later known as Washington High School, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Now bearing the name, Washington Pavilion, it opened its doors in 1999 as an arts and science center. Sioux Falls, South Dakota

- The Old Courthouse Museum, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Built in the 1800s.

Perhaps the most unusual construction involved Sioux quartzite and petrified wood:

- The Pettigrew home and museum

- Thomas and Jenny McMartin home, aka Pettigrew Home and Museum, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 1889

- The Sioux Falls Carnegie Library is located at 235 West 10th Street in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. It was built in 1903 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

- The former administration and high school buildings and the current gymnasium building on the South Dakota School for the Deaf campus

References

- National Register of Historic Places, Jasper Stone Company and Quarry

- Morey, B. G., 1985, Sedimentology of the Sioux Quartzite in the Fulda Basin, Pipestone County, southwestern Minnesota, in Southwick, D. L., cd., Shorter contributions to the geology of the Sioux Quartzite (Early Proterozoic), southwestern Minnesota: Minnesota Geological Survey Report of Investigations 32, pp. 59–74.

- Anderson, R. R., 1987, Precambrian Sioux Quartzite at Gitchie Manitou State Preserve, Iowa. Centennial Field Guide Volume 3: North-Central Section of the Geological Society of America: Vol. 3, No. 0 pp. 77–80.

- Van Schmus, W. R., Bickford, M, E., and Zietz, I., 1986, Early and Middle Proterozoic provinces in the central United States, in Kroner, A., ed., Proterozoic Lithospheric Evolution: American Geophysical Union Geodynamics series, v. 17, pp. 43–68.

- Goldich, S. S., Nier, A. O., Baagsgaard, H., Hoffman, J. H., and Krueger, H. W., 1961, The Precambrian geology and geochronology of Minnesota: Minnesota Geological Survey Bulletin 41, 193 p.

- U-Pb dating by Van Schmus, 1979, Geochronology of the southern Wisconsin rhyolites and granites: University of Wisconsin Extension, Geoscience Wisconsin, v. 2, pp. 9–24.

- Van Schmus, W. R., Thurman, M. E., and Petermann, A. E., 1975, Geology and Rb-Sr chronology of middle Precambrian rocks in eastern and central Wisconsin: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 86, pp. 1255–1265.

- Dott, R. H., Jr., 1983, The Baraboo interval; A tale of red quartzite Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, v. 15, p. 209.

- Ojakangas, R. W., and Weber, R. E., 1985, Petrography and paleocurrents of the Lower Proterozoic Sioux Quartzite, Minnesota and South Dakota, in Southwick, D. L., ed., Shorter contributions to the geology of the Sioux Quartzite (Early Proterozoic), southwestern Minnesota: Minnesota Geological Survey Report of Investigations 32, pp. 1–15.

- Bierman, P (1999). "Mid-Pleistocene cosmogenic minimum-age limits for pre-Wisconsinan glacial surfaces in southwestern Minnesota and southern Baffin Island: a multiple nuclide approach". Geomorphology. 27: 25. Bibcode:1999Geomo..27...25B. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(98)00088-9.

- Oliver Bowles (1918). The structural and ornamental stones of Minnesota. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 663. p. 205.

- The History of Jasper School. Geraldine Pedersen, curator, Jasper Historical Society

- National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places www.nps.org

- Sioux Falls History, by Rick D. Odland, Page 126, Arcadia Publishing 2007