Silbannacus

Mar.[1] Silbannacus is a mysterious figure believed to have been a usurper in the Roman Empire during the time of Philip I (244-249), or between the fall of Aemilianus and the rise to power of Valerian (253).

| Silbannacus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usurper of the Roman Empire | |||||||||

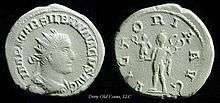

Antoninianus of Silbannacus | |||||||||

| Reign | sometime during reign of Philip the Arab, 244-249 or in 253 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Philip the Arab | ||||||||

| Successor | Philip the Arab | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Silbannacus had been known only from a single coin, an antoninianus reputedly found in Lorraine, which is now at the British Museum. This coin has an obverse with the portrait of the usurper and the legend IMP MAR SILBANNACVS AVG (Imperator Mar. Silbannacus Augustus), the reverse shows Mercury holding a Victoria and a caduceus, with VICTORIA AVG (Augusta Victoria) as legend. The name Silbannacus shows a Celtic origin, the "-acus" suffix; given the location of the coin, Silbannacus could have been a military commander in Germania Superior. As the coin was dated to Philip the Arab's age,[2] it is possible he revolted against Philip, with his revolt ending under Emperor Decius, since Eutropius (ix.4) reports a bellum civile was suppressed in Gaul during this emperor's rule.[3]

A second antoninianus was published in 1996, bearing the shortened legend MARTI PROPVGT (To Mars the defender). According to the style, the coin was coined in Rome; since the shortened legend is present on Aemilianus coins, in 253, Silbannacus might have prevailed here during the march of Valerian on Rome. An interpretation of these facts leads to Silbannacus being an officer who was left in garrison in Rome while his emperor, Aemilianus, left to face his rival Valerian. After the defeat and the death of Aemilianus in September 253, Silbannacus would have tried to become emperor with the support of the troops confined in Rome, thus controlling the monetary workshop, before being quickly eliminated by Valerian and his son Gallienus.[4]

Notes

- Possible resolutions of the gentile name are Marinus (Körner, Philippus Arabs, p. 386), Marius or Marcius (Estiot, L'empereur Silbannacus, p. 108).

- Roman Imperial Coinage 4.3, pp. 66 and 105 n. A. S. Robertson, Roman Imperial Coins in the Hunter Coin Cabinet. University of Glasgow, Vol. 3: "Pertinax to Aemilian", Oxford/ London/ Glasgow/ New York 1977, pp. Xf. XX, Anm. 2. XCV.

- F. Hartmann, Herrscherwechsel und Reichskrise. Untersuchungen zu den Ursachen und Konsequenzen der Herrscherwechsel im Imperium Romanum der Soldatenkaiserzeit (3. Jahrhundert n. Chr.), Frankfurt a. M./ Bern 1982 (Europäische Hochschulschriften, Ser. III, Vol. 149), pp. 63. 82. 94, n. 1.

- Estiot.

References

- Estiot, Sylviane, "L'empereur Silbannacus. Un second antoninien", in Revue numismatique, 151, 1996, pp. 105–117

- Körner, Christian, "Silbannacus", s.v. "Rebellions During the reign of Phillip the Arab (244-249 A.D.): Iotapianus, Pacatianus, Silbannacus, and Sponsianus", in DIR (1999).

- Körner, Christian, Philippus Arabs. Ein Soldatenkaiser in der Tradition des antoninisch-severischen Prinzipats. Berlin 2002 (Untersuchungen zur antiken Literatur und Geschichte 61), ISBN 3-11-017205-4.