Sign of contradiction

A sign of contradiction, in Catholic theology, is someone who, upon manifesting holiness, is subject to extreme opposition. The term is from the biblical phrase "sign that is spoken against", found in Luke 2:34 and in Acts 28:22, which refer to Jesus Christ and the early Christians. Contradiction comes from the Latin contra, "against" and dicere, "to speak".

According to Catholic tradition, a sign of contradiction points to the presence of Christ or the presence of the divine due to the union of that person or reality with God. In his book, Sign of Contradiction, John Paul II says that "sign of contradiction" might be "a distinctive definition of Christ and of his Church."[1]

Jesus Christ as sign of contradiction

Luke 2:34 refers to Jesus Christ while he is being presented in the temple by his parents. The words were spoken by Simeon to Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ, as a prophecy regarding her child and herself.

"Behold this child is set for the fall and rising of many in Israel, and for a sign that is spoken against (and a sword will pierce through your own soul also), that thought of many hearts may be revealed." (Italics added; Douay Rheims Bible translates the phrase as "sign that will be contradicted.")

The interpretation of the Navarre Bible, a Catholic bible commentary, is the following:

"Jesus came to bring salvation to all men, yet he will be sign of contradiction because some people will obstinately reject him -- for this reason he will be their ruin. But for those who accept him with faith Jesus will be their salvation, freeing them from sin in this life and raising them up to eternal life."

The commentary also says that Mary will be intimately linked with her Son's work of salvation. The sword indicates that Mary will have a share in her son's sufferings. The last words of the prophecy link up with verse 34: uprightness or perversity will be demonstrated by whether one accepts or rejects Christ.

There are three elements then involved in a sign of contradiction, according to Catholic theology: (1) An attack on Christ or people who are said to be "united" with Christ. From this attack, ensues a double-movement: (2) the downfall of those who reject Christ, and (3) the rise of those who accept him.

This double-movement is connected with the division Jesus Christ referred to in Luke 12:51-53, an external division among peoples who either follow him or not, but an internal peace for those who follow him.

"Do you think that I have come to give peace on earth? No, I tell you, but rather division; for henceforth in one house there will be five divided, three against two and two against three; they will be divided, father against son and son against father, mother against daughter and daughter against her mother, mother-in-law against her daughter-in-law and daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law." Jesus Christ was spoken against during his life: the Gospels claim that Pharisees and other critics said that he was allied with Beelzebub, that he was a drunkard and a glutton, (based upon his participation at banquets and feasts), that he was a blasphemer who made himself equal to God. According to Catholic theologians, these charges led to his torture and execution.

Throughout history, Jesus of Nazareth was also spoken against: Docetists, considered by the Catholic Church to be the first heretics, said that his body was not true but only an appearance. Arians said he was not God. Nestorius, the Patriarch of Constantinople, said Jesus' mother Mary was not the Mother of God, but only the mother of the human being called Jesus. Thus, Nestorius also denied that it is God the Son who became man.

In the 19th century, some questioned the historicity of Jesus, and in contemporary times, novels such as The Da Vinci Code and films such as The Last Temptation of Christ have portrayed him as romantically linked with Mary Magdalene.

According to the Catholic view, the double-movement that ensued after the attack on Christ is the following: While many of Christ's enemies have fallen (the Roman authorities and their empire fell in 476, the authorities in the Sanhedrin during his time died, their temple in Jerusalem destroyed in 70 AD by Titus), Jesus Christ resurrected from the dead and his religion became the largest religion in the world and the Catholic Church its biggest representation.

Catholic theologians also say that while the devil seemed to have been able to put the Messiah to death, his death turned the tables around and became the very instrument of Christ's victory over evil, death and the devil. His death showed the infinite love of God towards mankind ("Greater love no man has than he who lays down his life for his friend"), thus drawing men back to God. With his death he opened an infinite source of divine life (grace) through the seven sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, Holy Orders, Anointing of the Sick, Confession and the Eucharist, where Jesus Christ himself, both perfect God and perfect man, is present in person.

The Eucharist as a sign of contradiction

Catholic theologians also say that the Jesus Christ in the Eucharist is another sign of contradiction. Catholics believe that during the Last Supper, when Christ said, "This is my body," he was referring to the bread that he was holding, and that the bread became his Body in substance and in essence, retaining the "accidental" appearance of bread. Catholics call this "transubstantiation" from the Latin trans, "to change, to become, to transfer" and substantia, "substance, that which stands (stans) underneath (sub)". Substance refers to the core of each entity, e.g. the substance of a man is the same when he is a little baby and when he becomes an old man, even if the appearances are much different. In the case of transubstantiation, it is the substance that changed (from real bread to Jesus Christ) while the appearances (white, crunchy and smelling like bread) remained the same.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, for ten centuries this doctrine was unopposed, until Berengarius of Tours who taught in 1047 that "the body and blood of Christ are really present in the Holy Eucharist; but this presence is an intellectual or spiritual presence. The substance of the bread and the substance of the wine remain unchanged." Controversy was opened by the Reformation in the 16th century. Martin Luther taught that Christ was truly present in the Eucharist, with his doctrine being called the sacramental union. He was diametrically opposed by Zwingli who said the Eucharist is a symbolic memorial of Christ's redemptive death. John Calvin's view lay somewhere in between: instead of the substantial presence or the merely symbolic presence, he saw the presence as "dynamic": according to this view, at the moment of reception, the efficacy of Christ's Body and Blood is communicated from heaven to the souls of the predestined and spiritually nourishes them.

Towards the end of the 20th century, some Catholic priests put forth the doctrine of "trans-signification": a change of meaning on the part of those receiving it. The bread does not change, it is the meaning for the recipient that changes. "Trans-signification" is not in accordance with Catholic doctrine.

The opposition to transubstantiation, a doctrine considered by many to be holy, makes the Eucharist a sign of contradiction according to Catholic doctrine.

According to Catholic theologians, the double-movement is shown in (1) the breakup of the Protestants into thousands of denominations, with different views on the Eucharist, which for Catholic doctrine is the source of Church unity. According to the World Christian Encyclopedia (2001) by David B. Barrett, et al., there are "over 33,000 denominations in 238 countries." (including the rites of Catholicism) Every year there is a net increase of around 270 to 300 denominations, (2) the increase in devotion to the Eucharist all over the Catholic world.

The cross and mortification as signs of contradiction

Edith Stein, called the Patron of Europe by John Paul II, once taught on the day of the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, September 14, 1939:

- More than ever the cross is a sign of contradiction. The followers of the Antichrist show it far more dishonor than did the Persians who stole it. They desecrate the images of the Cross, and they make every effort to tear the cross out of the hearts of Christians. All too often they have succeeded even with those who, like us, once vowed to bear Christ's cross after him. Therefore, the Savior today looks at us, solemnly probing us, and asks each one of us: Will you remain faithful to the Crucified? Consider carefully! The world is in flames, the battle between Christ and the Antichrist has broken into the open. If you decide for Christ, it could cost you your life.

The practice of mortification, a way of following Christ's advice to his disciples to "renounce yourself, take up your cross, and follow me" is also usually attacked as sado-masochism, a search for pleasure through pain. Catholics believe, on the other hand, that it is through suffering and pain that Christians "complete in themselves the afflictions of Christ" as St. Paul preached. This means Christians see themselves as forming the "one mystical person" with Christ, and therefore should help people by loving and obeying God by undergoing pains and sufferings, thus making up for the sins of men.

Views on the cross creates a division: "The division between those whose first love is God, and those whose first love is self - might also be expressed as the division between those who accept the place of the Cross in the following of Christ, and those who reject all sacrifice except it be for personal gain."

St. Paul said "many live as enemies of the cross of Christ." (Philippians 3:18) He preached: "The message of the cross is complete absurdity to those who are headed for ruin, but to those of us who are on the way to salvation it is the power of God.... The Jews demand signs (miracles), and the Greeks wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified - to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Gentiles foolishness; but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ, the power of God and the wisdom of God" (1 Corinthians 1:18,22).

The Church and Christians as signs of contradiction

The second biblical phrase is from Acts 28:22, quoting a Jew in Rome with whom Paul was talking:

- We desire to hear from you what your views are: for with regard to this sect we know that everywhere it is spoken against. (Italics added)

According to Catholic theologians and ecclesiologists like Charles Journet and Kenneth D. Whitehead in One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: The Early Church was the Catholic Church, the sect being referred to here by the Jews is the early church of Christians.

The Church and the early Christians, according to these Catholic theologians, are one with Jesus Christ. As an example, they say that when Paul was persecuting the early Church, Jesus Christ appeared to him and said: Why do you persecute me?

The passage from the Acts of the Apostles is related to John 15:5-8:

- "I am the vine, you are the branches. Whoever remains in me and I in him will bear much fruit, because without me you can do nothing. Anyone who does not remain in me will be thrown out like a branch and wither; people will gather them and throw them into a fire and they will be burned. If you remain in me and my words remain in you, ask for whatever you want and it will be done for you. By this is my Father glorified, that you bear much fruit and become my disciples." (italics added)

This passage shows the double-movement depending on the two possible attitudes towards Christ: whoever is united to Christ in holiness will rise and bear fruit, while those who are disunited to Christ will fall down and wither.

The early Church and the Roman Empire

The early Christians, regarded as forming a pernicious sect by several authorities of the Roman Empire, are also seen as a sign of contradiction. Early Christians were called cannibals (for reputedly eating the "body of Christ"), they were called atheists (for not following the established Roman religion), they were also accused of burning Rome during the time of the Emperor Nero, and thus were tortured and burned as torches. Emperors after Nero also saw them as a threat to the unity of the Empire.

Tertullian, an early Christian apologist, said that the persecution of the first Christians helped in propagating Christianity: "The blood of martyrs is the seed of Christians." According to Catholic historians like Philip Hughes and Warren Carrol, when the Empire fell in 476 AD, Christianity continued to prosper and to spread throughout Europe and beyond. These historians say that it was the Christian monks who eventually tried to keep intact the ancient culture in their monasteries.

Early Church Fathers

Many Catholic Church Fathers are also seen by theologians as signs of contradiction. A specific example is St. Athanasius or Athanasius of Alexandria, who defended the divinity of Christ, the basic reason behind the Christian religion, according to Patrologist Johannes Quasten.

J. Quasten says that Athanasius was the deacon and secretary to bishop Alexander of Alexandria. As such he attended the Council of Nicea in 325 where he fought for the defeat of Arianism and acceptance of the divinity of Jesus. Against Arius who said that Jesus Christ was not eternal and not God but a mere creature, Athanasius formulated the doctrine that Jesus Christ is "consubstantial" with the Father, a doctrine now known as "homoousios."

Athanasius later became the Patriarch of Alexandria, Egypt in 328. When the Arians gained political power, Athanasius was exiled five to seven times, but was restored to authority each time. This gave rise to the expression "Athanasius contra mundum" or "Athanasius against the world."

While Arius, his opponent, died in 336, Athanasius died in 373 surrounded by the affection of his flock, and from then on revered as a great saint in Christendom. (J. Quasten, Patrology) Athanasius has been recognized by the Catholic Church as a Church Father, a leading testimony of Sacred Tradition. He has also been declared a Confessor of the faith and Doctor of the Church.

The Society of Jesus and the Suppression

After Ignatius of Loyola's death and through the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, the Jesuits became widely known as the schoolmasters of Europe, in part for their reputation as scholars and their demonstrated intellectual excellence as shown through the thousands of textbooks they authored. They were also known for their unity with the Pope, which was made explicit by taking a fourth vow: obedience to the Pope.

Their status in Europe greatly changed in 1773 when Pope Clement XIV gave in to pressure from groups across the continent. Pope Clement feared that many would follow the example of Henry VIII of England who abandoned the Catholic Church. On the heels of the pope's suppression of the Jesuits, many of the Jesuit's educational institutions fell under state government control, and much of the Jesuit's books and teaching materials were subsequently destroyed. Over 200 members of the order fled to Russia while over 20,000 others scattered throughout the world. Pope Pius VII lifted this suspension in 1814 and the Jesuits re-emerged as they were asked by many governments to return to the colleges they once gave up. The absolutist monarchs who had demanded the suppression had fallen by then, swept by the forces unleashed by the French Revolution of 1789.

The period following the Restoration of the Jesuits in 1814 was marked by tremendous growth, as evidenced by the large number of Jesuit colleges and universities established in the 19th century. In the United States, 22 of the Society's 28 universities were founded or taken over by the Jesuits during this time. Some claim that the experience of suppression served to heighten orthodoxy among the Jesuits upon restoration.

Pius VII and Napoleon

.jpg)

Another example of a sign of contradiction is the life of Pius VII. His was a difficult pontificate filled with moral and physical problems inflicted by Napoleon I whom the pope himself consecrated Emperor of the French in Notre Dame in Paris. As his armies were conquering many countries of Europe, Napoleon, who was a proponent of liberalism, is reported to have said to Church officials, Je détruirai votre église ("I will destroy your Church").[2] Later Napoleon took Pope Pius VII prisoner and sent him to Fontainebleau.

The Columbia University Encyclopedia states: "In 1814, after Napoleon's downfall, Pius returned to Rome in triumph. One of his first acts was to restore the Society of Jesus. The Papal States were restored at the Congress of Vienna, and a series of concordats were signed with European powers. At the same time Pius VII's stolidity in the face of humiliation began a revival of personal popularity for the pope that has since characterized Catholicism."

Pius VII later offered asylum to Napoleon's elderly mother and gave both moral and material assistance to his family. Napoleon died in exile 1821 at the age of 52; Pope Pius VII died in 1823 in Rome at the age of 81.

John Paul II

A contemporary example seen by many as of a sign of contradiction is Pope John Paul II.[3] While Pope, he was called a reactionary and an ultraconservative, and was often criticized, stridently at times, by the media, non-Catholic and Catholics alike. He was criticized for his views on sex, homosexuality, birth control, and the role of women in the church. He was criticized for some of his canonizations, including the canonization of Opus Dei's founder, Josemaría Escrivá.

According to George Weigel, in Witness to Hope, even many Catholic theologians, especially those who had relativist and secularist tendencies, rebelled against his teaching magisterium, criticizing his views about morality, ecumenicism, the sacraments, and the ordination of women. Weigel also says that there were many attempts to assassinate him. He mentions some historians and investigators who made very plausible connections with communist leaders who feared his influence in Eastern Europe. When he died, the communist governments in the Eastern Europe had already fallen. Traditionalists criticized him for being too open to other religions. On the other hand, on his death, he was highly praised by many, both Catholics and non-Catholics.

According to Weigel and other Catholic commentators like John Allen, John Paul II has been praised for and will be much remembered for the following things:

- his revolutionary Theology of the Body which gives profound insights on human sexuality, his clear moral teachings in Veritatis Splendor,

- his fight for human rights and dignity which led to the fall of dictatorships and of communism,

- his defense of life and the human embryo through unprecedented infallible teachings on abortion, euthanasia, and murder as grave sins in the Encyclical Evangelium Vitae,[4]

- his push for the universal call to holiness through his many canonizations and his "program for all times," At the Beginning of the New Millennium (Novo Millennio Ineunte) which place sanctity as the number one priority of all pastoral activities in the Catholic Church,

- his teaching on reason as being congruent with the Catholic faith (Fides et Ratio),

- the strides in the work of ecumenism and

- the work on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which, claim Weigel and some historians of theology, has cleared much of the doctrinal confusion which disturbed the Church and society in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

Prelature of Opus Dei and the Holy Cross

Opus Dei, described as one of the most controversial forces in the Roman Catholic Church, is another contemporary sign of contradiction according to some Catholic theologians.

Opus Dei was denounced as a heresy by churchmen in the 1940s but is now considered one of the contributors to a central doctrine of the Second Vatican Council, the universal call to holiness and is supported by various Catholic leaders. Catholic historians say that it was attacked as pro-Franco (because of eight members were ministers, some at the same time) but some of its members driven into exile by Franco's political arm later became Senate Presidents in the new democracy. It has been criticized as a cult for various reasons. However, the late John Paul II said that its teachings on the radical demands of sanctity belongs to all Christians. John Carmel Heenan, Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, commented in 1975: "One of the proofs of God's favour is to be a sign of contradiction. Almost all founders of societies in the Church have suffered. Monsignor Escrivá de Balaguer is no exception. Opus Dei has been attacked and its motives misunderstood. In this country and elsewhere an inquiry has always vindicated Opus Dei."[5] John Paul II, in his decree on Escrivá's heroic virtues, stated: "God allowed him to suffer public attacks. He responded invariably with pardon, to the point of considering his detractors as benefactors. But this Cross was such a source of blessings from heaven that the Servant of God's apostolate spread with astonishing speed."

Escrivá said that Opus Dei in order to be effective has to live like Jesus Christ and that "its greatest glory is to live without human glory."

Catholic Martyrs of the 20th Century

Writing for Catholic Herald, Robert Royal, president of the Faith and Reason Institute, Washington, D.C. reported about the results of his research which appeared in his book The Catholic Martyrs of the Twentieth Century: A Comprehensive Global History.[6] Royal states that in some countries, such as Spain, the Church has documented almost 8,000 people killed for the Catholic faith during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). Royal says, from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, to Nazi Germany, Africa, Asia, and Latin America, thousands of Catholics have disappeared into gulags, been gunned down by dictators, had their heads cut off by anti-Catholic fanatics, and, in some cases, been crucified.

In Sudan, which Royal says is engaged in the most insidious anti-Catholic campaign in the world, there have been reports not only of martyrdoms and crucifixions, but of Christians in the Nuba mountains in southern Sudan being sold into slavery. It is estimated that over 1.5 million Christians have been killed by the Sudanese army, the Janjaweed, and even suspected Islamists in northern Sudan since 1984. Royal states that China, for example, has produced large numbers of martyrs. In the 1900 Boxer Rebellion alone, 30,000 Catholics died, including several dozen bishops, priests, and religious. Since the creation of the People's Republic following the end of the civil war in 1949, thousands more have died in laojiao (labor camps), facing conditions that Royal describes as brainwashing and slave labor.

Human beings as signs of contradiction

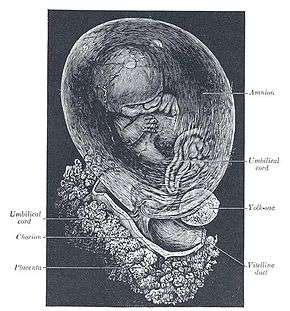

The human embryo, according to Catholics, is also a sign of contradiction. According to Catholic belief, the human embryo is already a human being, as much as the human fetus and the newborn child. And for Christians, a human being is made in the image and likeness of God. The fact that these beliefs are highly contested by many quarters makes the human embryo, in the Catholic view, a sign of contradiction.

Elio Sgreccia, Vice President of the Pontifical Council for Life, said in an article entitled "The Embryo: A Sign of Contradiction":

- We need only look at the data bank of bioethical and medical writing on the subject to see how this is so. In the years 1970-1974 more than five hundred works dealing with the biomedical aspect of the question existed, and there were 27 works of a philosophical-theological character. In the years 1990-1994 there were nearly 4,200 works on the biomedical dimension of the subject and 242 on the philosophical-theological aspect of the debate. A quotation from one of the Fathers of the Church, Tertullian: "homo est qui venturus est." [trans: he who will become man is man] From the moment of fertilization we are in the presence of a new, independent, individualized being which develops in continuous fashion.[7]

Sacred things as signs of contradiction

The Shroud of Turin, an image viewed by some Christians as a miraculous imprinting of the image of Jesus on the cloth, together with the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, are disputed as authentic supernatural depictions. For this reason, some Catholics consider them to be signs of contradictions.

Sign of Contradiction by John Paul II

Sign of contradiction is also the title of Lenten meditations he preached and wrote upon the request of Paul VI. The theme of the book, according to one review, is "the human encounter with God in a world that seems to contradict the reality of divine power and love." John Paul II says in his conclusion that "It is becoming more and more evident that those words (Luke 2:34) sum up most felicitously the whole truth about Jesus Christ, his mission and his Church."

See also

- Foolishness for Christ

- Hermit and Stylite: Vocations to solitude for the life of the world.

Endnotes

- John Paul II, Sign of contradiction, St. Paul Publications 1979, p. 8.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-04-04. Retrieved 2006-03-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Others who say Opus Dei is a sign of contradiction are: Piers Paul Read, Vittorio Messori, Richard Gordon Archived 2006-11-11 at the Wayback Machine, Manuel María Bru Alonso, Eulogio Lopez.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2005-12-02. Retrieved 2005-10-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/hlthwork/documents/rc_pc_hlthwork_doc_05101997_sgreccia_en.html

References

- Wojtyla, Karol. Sign of Contradiction.

- Woods, Thomas. How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization.

- Quasten, James. Patrology.

- Carrol, Warren. History of Christendom.

- Journet, Charles. The Church.

- Allen, John. Opus Dei: An Objective Look at the Most Controversial Force in the Catholic Church.

- Casciaro, Josemaria, et al. Navarre Bible.

- José Miguel Cejas, Piedras de escandalo