Sibylla's

Sibylla's was a nightclub in the West End of London that operated from 1966 to 1968. It was located at 9 Swallow Street, on the edge of Mayfair and close to Piccadilly Circus.[1] The club's launch on 22 June 1966 was attended by many artists and celebrities, including the Beatles, members of the Rolling Stones, Michael Caine, Julie Christie, David Bailey and Mary Quant. Like the Ad Lib and the Scotch of St. James, the club was a popular meeting place for rock musicians and other artists until trends changed in the London scene.

Sibylla's was conceived as an exclusive venue for leading figures in the Swinging London era. Its major shareholders and owners were advertising copywriter Kevin Macdonald, photographer Terry Howard, and property developer Bruce Higham, while baronet and champion horse rider William Pigott-Brown provided much of the finance for the venture. George Harrison of the Beatles was given a shareholding in the club, in return for the publicity his association would bring, and disc jockey Alan Freeman was also a shareholder. The club's interior was designed by David Mlinaric. Since Sibylla's closed, the site has continued to be a nightclub location.

Concept and launch

In their plan for the club, Kevin Macdonald, Terry Howard and Bruce Higham conceived of a meeting place for the elite of Swinging London. Higham said the clientele they envisaged "[have] a kind of self-confidence, an awareness, which they transpose to their environment".[2] As a great-nephew of newspaper proprietor Lord Northcliffe, MacDonald was from an aristocratic family, yet his interest was in establishing an elite that was not governed along lines of social class.[3]

Sir William Pigott-Brown, a baronet, provided half the funds for the venture.[4] Guinness heir Tara Browne was another of the financial backers.[5] George Harrison of the Beatles, a friend of Howard, was given a 10 per cent shareholding, on the understanding that his name could be used to attract publicity, and disc jockey Alan Freeman was also a stakeholder.[6][nb 1]

The site at 9 Swallow Street, on the eastern edge of Mayfair, had been a nightclub venue since 1915.[1] The building's new interiors were designed by David Mlinaric, who said at the time that his concept was to give the club "a feeling of under-decoration" to match contemporary fashions in clothes design.[8] Macdonald, Howard and Higham named the venue after Sibylla Edmonstone,[9][10] a London socialite and the granddaughter of American entrepreneur Marshall Field.[8] The club was run under the company name of Kevin Macdonald Associated Ltd.[11]

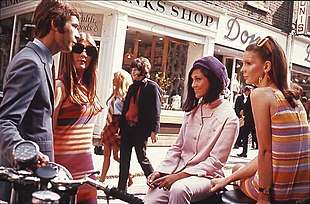

Sibylla's was launched with a private party held on 22 June 1966.[12] One of the three owners declared that the club was "the first Classic London Discotheque".[13] Among the guests were the Beatles, who had just finished recording their Revolver album that day. The full guest list was later published in Queen magazine and included Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones; actors Michael Caine, Julie Christie and Jane Birkin; and fashion figures such as David Bailey, Mary Quant and Michael Rainey.[6] Writing in Queen, television presenter Cathy McGowan said that "A more glittering line up of guests could hardly be imagined."[14]

Popularity and decline

In his book on 1960s London, Shawn Levy states that, in their policy for Sibylla's, Macdonald, Howard and Higham allowed exclusivity based on "hipness" to replace the old class divisions of "breeding, schooling and wealth". Levy adds, "Of course, it worked", as 800 of the people they contacted agreed to become members of the club, at an annual fee of around £8.[15] Along with the Ad Lib and later the Scotch of St. James, the club was a popular meeting place for rock musicians such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.[16]

Speaking to journalist and author Jonathan Aitken in 1966, Macdonald said that Sibylla's represented the classless society of Swinging London. He said that he and his co-owners had brought together "the new aristocracy in Britain … the current young meritocracy of style, taste and sensitivity", namely: "the top creative people; the top exporters; the top brains; the top artists; the top social people".[17][nb 2] According to MacDonald, in its "marrying up" of working-class artists and photographers with members of high society, Sibylla's was the realisation of the psychedelic aesthetic, a trend that had emerged in contemporary music that year.[19]

The club's manager was Laurie O'Leary, who had previously managed Esmeralda's Barn, a nightclub in Knightsbridge owned by the Kray twins.[20] The musical acts who performed at Sibylla's included Jokers Wild, a band featuring future Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour,[21] and were booked through an agency owned by the Krays' elder brother, Charlie Kray.[20] Freddie Foreman, a convicted associate of the Kray twins, later wrote that, despite the restrictive door policy at Sibylla's, "I always welcome at the club" due to O'Leary's presence.[20][22]

In October 1966, Macdonald, who was suffering from depression, died after jumping from a rooftop in west London. Author Steve Turner describes him as an early casualty among London's psychedelic drug users, at a time when the full psychological effects of LSD were not widely known.[23] According to cultural historian David Simonelli, MacDonald's suicide was indicative of the downside of "the changes in British society and its sociocultural image" in the psychedelic era.[24] Tara Browne, who was a regular at the club in the company of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones,[25] died after crashing his sports car into a parked van in December 1966.[5]

In 1968, O'Leary left Sibylla's to manage the Speakeasy Club, which had become the new night spot for musicians and record industry executives.[26] Sibylla's closed that same year, as a result of what Levy terms "the vagaries of fashion among its In Crowd membership".[27] Following its closure, 9 Swallow Street continued to be a nightclub venue.[1] On 24 October 2016, the Aristocrat opened on the site,[28] applying a restrictive door policy that, according to GQ magazine, outdoes all rival local clubs.[29]

Notes

- Advance reports stated that Harrison and Freeman were co-funding the club.[4] Harrison merely lent his name to the project, however, and was not an investor.[7]

- Writing in the Daily Express that year, Robin Douglas-Home, a Scottish aristocrat, recognised that London's "privileged class" was now "actors, pop singers, hairdressers, and models". As a contrast with the previous norm, he added: "If a 14th Earl with a grouse moor and George Harrison with [his wife, the model] Patti Boyd walked together into a restaurant and there was only one table left, who would be given the table? Well – if the head waiter had any sense – obviously George and Patti."[18]

References

- Du Noyer 2010, p. 101.

- Levy 2003, pp. 217–18.

- Simonelli 2013, p. 99.

- KRLA Beat staff (25 June 1966). "George's Club". KRLA Beat. p. 1.

- Telegraph staff (22 June 2012). "Nicky Browne". The Telegraph. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Turner 2016, pp. 327–28.

- Turner 2016, p. 327.

- KRLA Beat staff (25 June 1966). "George's Club (continued)". KRLA Beat. p. 6.

- Turner 2016, p. 329.

- Levy 2003, pp. 218–19.

- Harry 2003, p. 58.

- Turner 2016, p. 650.

- Levy 2003, p. 217.

- "Give us this day our daily bird #3 – Sibylla Edmonstone". Snap Galleries. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- Levy 2003, p. 218.

- Du Noyer 2010, pp. 100–01.

- Turner 2016, pp. 329–30.

- Turner 2016, pp. 330–31.

- Simonelli 2013, pp. 99–100.

- Turner 2016, p. 328.

- Blake 2008, p. 106.

- Foreman 2007, p. 78.

- Turner 2016, p. 532.

- Simonelli 2013, p. 120.

- Du Noyer 2010, p. 107.

- "Tour Manager". laurieoleary.co.uk. 15 March 2017.

- Levy 2003, p. 220.

- "Aristocrat: The Elite's Club". The Handbook. 21 October 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Halls, Eleanor (10 February 2017). "Aristocrat Nightclub Brings Laid Back Chic to Mayfair". GQ. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Sources

- Blake, Mark (2008). Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81752-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Du Noyer, Paul (2010). In the City: A Celebration of London Music. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-753515747.

- Foreman, Freddie (2007). Freddie Foreman: The Godfather of British Crime. London: John Blake. ISBN 978-1-84454-689-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harry, Bill (2003). The George Harrison Encyclopedia. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-753-50822-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levy, Shawn (2003). Ready, Steady, Go!: Swinging London and the Invention of Cool. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-84115-226-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simonelli, David (2013). Working Class Heroes: Rock Music and British Society in the 1960s and 1970s. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-7051-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York, NY: HarperLuxe. ISBN 978-0-06-249713-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Aitken, Jonathan (1967). The New Meteors. London: Secker & Warburg.

- Norman, Philip (1996) [1981]. Shout!: The Beatles in Their Generation. New York, NY: Fireside. ISBN 0-684-83067-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Opening night at Sibylla's – photo gallery at Getty Images