Siamese–Vietnamese War (1841–1845)

The 1841–1845 Siamese-Vietnamese War in Cambodia (Thai: อานัมสยามยุทธ (พ.ศ. 2384 - พ.ศ. 2388), Vietnamese: Chiến tranh Việt–Xiêm (1841-1845)) was a military conflict between Đại Nam (Vietnam), ruled by the Nguyen emperor Thiệu Trị and the Kingdom of Siam under the rule of Chakkri king Nangklao. The rivalry between Vietnam and Siam over the control of the Cambodian heartlands in the Lower Mekong basin had intensified after Siam's failed attempt to conquer Cambodia during the previous war from 1831 until 1834. Nguyen Emperor Minh Mạng installed Princess Ang Mey to rule Cambodia as puppet queen regnant of his choice in 1834, declaring full suzerainty over Cambodia, which he thereby demoted to become Vietnam's thirty-second province, the Western Commandery (Trấn Tây Province).[1] In 1841 Siam seized the opportunity of discontent and a Khmer revolt against Vietnamese rule and King Rama III sent an army to enforce Prince Ang Duong's installation as King of Cambodia. After four years of attritional struggle, both parties agreed to a compromise peace and placed Cambodia under joint rule.[2][3][4][5]

| Siamese-Vietnamese war (1841–45) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Siamese–Vietnamese Wars | |||||||

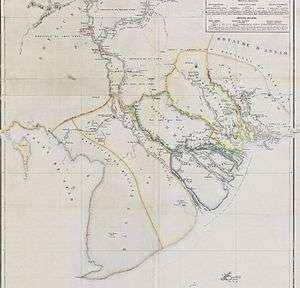

A map showing the movement of Vietnamese troops (from June to December 1845) during the Vietnam-Siamese War (1841–1845). | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

former Cambodian queen, princes and ministers: |

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Background

The once powerful kingdom of the Khmers had during the 18th century become under increasing influence by its eastern and western neighbors Vietnam and Siam. During the reign of the youthful Khmer king Ang Eng (1779–96) Siam conquered Cambodia's Battambang and Siem Reap provinces in the west. The provincial administrators became vassals under direct Siamese rule.[6][7] In the early 17th century Siam first adopted the tradition to take members of the Cambodian royal family hostage and took them to the court at Ayutthaya, where they were left to be influenced and to compromise each other under Siamese scrutiny. The Vietnamese court in Huế also established these methods and skillfully orchestrated their protégées and interfered in marriage policies. Quarrels among the royal contenders greatly diminished any chances to restore an effective Kingship in Cambodia for many decades.[8][9][5]

After Siam's defeat in the 1831–1834 war, the Vietnamese re-installed King Ang Chan to the Cambodian throne. Prince Ang Em who had been a Siamese hostage was made the governor of Battambang by Chao Phraya Bodindecha (Battambang and Siem Reap had been under direct Siamese rule since 1794).[10] However, King Ang Chan died in January 1834, who had four daughters but no male heir. In 1834 Emperor Minh Mạng chose Princess Ang Mey to rule Cambodia as a queen regnant. However, Queen Ang Mey was only a puppet queen without royal powers as the Nguyễn dynasty incorporated Cambodia into the Vietnamese empire as the Trấn Tây Province. Vietnamese administration of Cambodia was bestowed to Trương Minh Giảng, who was appointed Viceroy. The Trấn Tây Province government was based in Phnom Penh. Emperor Minh Mạng had decreed elaborate plans and designs for cultural, economic and ethnic development and assimilation of Cambodia and forwarded these to Trương Minh Giảng. However, economic and societal realities of Cambodia frustrated all efforts and hardly any progress had been made in more than a decade.[1][11]

Prince Ang Em, governor of Battambang resolved to take actions against the humiliating reign of queen Ang Mey. In December 1838 Ang Em defected from Siamese tutelage to Vietnam and arrived in Phnom Penh hoping that Trương Minh Giảng would make him king. Trương, however, arrested Ang Em and sent him to Huế. Siamese general Chaophraya Bodindecha marched from Bangkok to Battambang in 1839 to alleviate the situation. In 1840, the Cambodians had risen against Vietnamese rule in open rebellion. The Cambodian governor of Pursat met Bodindecha and urged him to expel the Vietnamese, who held garrisons in all notable settlements in Cambodia. Bodindecha endorsed Prince Ang Duong, Ang Em's younger brother, as the new Siamese candidate for the Cambodian throne.[12][13][5]

Military campaigns

Siamese Offensives of 1841-42

.jpg)

In November 1840 Siam's warlord Chaophraya Bodindecha sent troops led by his son Phra Promborrirak and his brother-in-law Chao Phraya Nakhon Ratchasima Thongin from Battambang to lay siege on Pursat, which was held by Vietnamese forces. Bodindecha also sent forces led by Phraya Rachanikul to take Kampong Svay, which was occupied by Đoàn Văn Sách. The Siamese were able to take Kampong Svay, however, Trương Minh Giảng retook Kampong Svay and proceeded to Pursat. Bodindecha then negotiated a peaceful surrender with the military commander of Pursat before Trương Minh Giảng could reach him. Emperor Minh Mạng, who had sent reinforcements under Phạm Văn Điển, died after he fell from a horse in February 1841. The new emperor, Thiệu Trị, reversed Vietnamese policies on Cambodia and ordered the retreat of all Vietnamese forces. By October 1841, the Vietnamese had retreated to An Giang Province. Viceroy Trương Minh Giảng evacuated Phnom Penh and committed suicide, taking responsibility for the loss of Cambodia. The Vietnamese had taken the defected Prince Ang Em to An Giang in order to rally Cambodian support. Bodindecha, however now unopposed, sent his son Phra Promborrirak to help Prince Ang Duong to the throne in Oudong and massacre all remaining Vietnamese people, still dispersed in Cambodia.[1]

After Siamese dominance was established in Cambodia, King Rama III ordered the Vĩnh Tế Canal at the Cambodian/Vietnamese border, which enabled Vietnamese naval forces to quickly access the Gulf of Thailand, should be destroyed. Bodindecha reminded the king that the canal was guarded by strong Vietnamese forces in Hà Tiên and An Giang. More troops were required to attack the area. The king thus sent his half-brother Prince Isaret (later Vice-king Pinklao), accompanied by Chuang Bunnag (son of Phraklang, later Somdet Chao Phraya Sri Suriyawongse) and five brigantines to attack Hà Tiên (Banteay Meas) and a land force led by Chao Phraya Yommaraj Bunnag and Prince Ang Duong to attack An Giang Province.

The fleet of Prince Isaret and Chuang Bunnag arrived at Phú Quốc island in January 1842. Prince Isaret stayed on the island while ordering Chuang Bunnag to attack Hà Tiên. Chuang Bunnag led the Siamese brigantines to attack Hà Tiên while sending a Cambodian force to take Cô Tô mountain. The Siamese artillery shelled Hà Tiên intensely. Đoàn Văn Sách the defender of Hà Tiên reinforced the city, which did not fall. After a whole week of attacks, Chuang Bunnag was still unable to take Hà Tiên. Chuang then visited Prince Isaret at Phú Quốc, who decided to retreat due to the overwhelming Vietnamese numbers and the unfavorable winds. Nguyễn Tri Phương led the Vietnamese forces to capture Cô Tô from the Cambodians. Prince Isaret and Chuang Bunnag then led the Siamese forces to return to Chantaburi.[1]

At the An Giang front, Chao Phraya Yommaraj Bunnag and Prince Ang Duong had led Siamese armies in January 1842 to take the Vĩnh Tế Canal and An Giang province, penetrating into Hậu Giang Province. Nguyễn Công Nhân was unable to repel the Siamese attacks and Thiệu Trị sent Tôn Thất Nghị with reinforcements. Phạm Văn Điển, the governor of the An Giang and Hà Tiên Provinces, had joined in the defense of An Giang but died of illness in April 1842.[14] Tôn Thất Nghị and Nguyễn Công Nhân pushed the Siamese back. The Siamese were defeated at Châu Đốc, suffering heavy losses, and retreated to Phnom Penh. Nguyễn Công Nhân was made new governor of An Giang and Hà Tiên Provinces.[5]

Interbellum (1842-45)

Famine and diseases ravaged Cambodia from 1842 to 1843 and the war came to a halt as both warring parties were exhausted of manpower and resources. On the Siamese side, Prince Ang Duong and his guardian Phra Promborrirak retreated to Oudong, supported by Bodindecha at Battambang. On the Vietnamese side, Prince Ang Em had come from Huế and joined Nguyễn Tri Phương at Châu Đốc. However, Prince Ang Em died in March 1843, leaving only princess Ang Mey under Vietnamese control. Bodindecha abandoned Phnom Penh and returned to Bangkok in 1845.[1]

Vietnamese Offensives of 1845

The Siamese campaigns of 1841 had failed to bring about lasting peace, but greatly devastated and depopulated large areas of central, south and southeastern Cambodia, which antagonized many Cambodians and by 1845 several noblemen among Prince Ang Duong's court expressed their desire to seek an allegiance with the Vietnamese rather than with Siam. Emperor Thiệu Trị launched an offensive into Cambodia in three groups[15] with Võ Văn Giải, governor of Gia Định Province and Biên Hòa Province as supreme commander. Nguyễn Văn Hoàng, admiral of An Giang led a Vietnamese fleet from Tân Châu upstream the Bassac River to attack Ba Phnum. Doãn Uẩn, commander of An Giang, would proceed through Kampong Trabaek District. Both armies would meet at Ba Phnum and jointly attack Phnom Penh. The fleet led by Nguyễn Công Nhân from Tây Ninh would follow and reinforce the first two armies.[5]

After Prince Ang Duong had the outspoken Vietnamese sympathizers at his court executed in May 1845, the armies began to advance. Nguyễn Văn Hoàng marched along the Bassac River and after defeating a Cambodian contingent at Preak Sambour, proceeded to Ba Phnum. Doãn Uẩn captured Kampong Trabaek and set up camp at Khsach Sa. Bodindecha hurriedly marched via Battambang to Oudong to defend the capital. Nguyễn Văn Hoàng and Doãn Uẩn converged at Ba Phnum. Võ Văn Giải arrived from Saigon at Ba Phum to command forces and Nguyễn Tri Phương led reinforcement troops from Châu Đốc to Ba Phnum. Nguyễn Tri Phương and Doãn Uẩn attacked Phnom Penh in September 1845. Phnom Penh was defended by Phra Promborrirak, Bodindecha's son. Nguyễn Tri Phương managed to capture Phnom Penh. Phra Promborrirak and the Siamese forces suffered heavy losses and retreated to Oudong.

Nguyễn Văn Chương besieged Oudong, which was defended by Bodindecha. Nguyễn Tri Phương was stationed at Ponhea Leu to the south of Oudong and Doãn Uẩn was stationed at Kampong Luong to the north. After some minor clashes, both sides agreed to negotiate. Doãn Uẩn requested that Prince Ang Duong send a mission to Huế, apologize and submit to Vietnamese rule. After five months, Nguyễn Tri Phương and Doãn Uẩn lifted the siege and returned to Phnom Penh in November 1845.[1]

Peace negotiations

The Vietnamese had to repeatedly send letters to Ang Duong at Oudong and urge him to submit to Vietnamese rule and promised to return the Cambodian royal hostages including his mother. However, Prince Ang Duong and Bodindecha remained silent. Only after the Vietnamese had sent an ultimatum in October 1846 an agreement was finally reached in January 1847. Prince Ang Duong would be crowned King and tributes would be submitted to both courts at Bangkok and Huế. The Cambodian courtiers and princesses returned to Oudong. Prince Ang Doung sent letters to Emperor Thiệu Trị at Huế, who invested him as King of Cambodia and in January 1848, King Rama III also officially invested Ang Duong as King. The war had thus come to an end. This peace lasted until the French colonial empire established a protectorate in 1863.[1]

References

- Kiernan, Ben (17 February 2017). Viet Nam: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-0-19-062729-4.

- Schliesinger, Joachim (2017). The Chong People: A Pearic-Speaking Group of Southeastern Thailand and Their Kin in the Region. Booksmango. pp. 106–. ISBN 978-1-63323-988-3.

- Childs Kohn, George (2013). "Siamese-Vietnamese War of 1841–45". Dictionary of Wars. Taylor & Francis. pp. 646–. ISBN 978-1-135-95501-4.

- Hirakawa, Sachiko (2004). "Siamese-Vietnamese Wars". In Bradford, James C. (ed.). International Encyclopedia of Military History. Routledge. pp. 1235–. ISBN 978-1-135-95034-7.

- Vũ Đức Liêm. "Vietnam at the Khmer Frontier: Boundary Politics, 1802–1847" (PDF). Hanoi National University of Education. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Rungswasdisab, Puangthong (1995). War and trade: Siamese interventions in Cambodia 1767-1851 (PhD). University of Wollongong. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2002). "Thailand". The Greenwood Encyclopedia of International Relations. ISBN 9780313323836. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- Vickery, Michael (1996). "Mak Phœun : Histoire du Cambodge de la fin du XVIe au début du XVIIIe siècle" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. 83: 405–415. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

At the time of the invasion one group of the royal family, the reigning king and two or more princes, escaped and eventually found refuge in Laos, while another group, the king's brother and his sons, were taken as hostages to Ayutthaya.

- Vickery, Michael (2011). "'1620', A Cautionary Tale" (PDF). In Aung-Thwin, Michael Arthur; Hall, Kenneth R. (eds.). New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia, Continuing Explorations. London: Routledge. pp. 157–166. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

Cambodia had quickly recovered from an Ayutthayan invasion of Lovek in 1593-94

- "พระตะบอง เสียมเรียบ ศรีโสภณ "รอยสยาม" และ "สามจังหวัด"กัมพูชา".

- Bun Srun Theam (1981). Cambodia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century: A Quest for Survival, 1840-1863 (PDF) (MA). Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Schliesinger, Joachim (2017). Chanthaburi City: An Ancient, Multiethnic and Significant Municipality in Southeastern Thailand. Booksmango. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-1-63323-987-6.

- Martin, Marie Alexandrine (1994). Cambodia: A Shattered Society. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07052-3.

- "Đại Nam 3 lần đánh bại Xiêm La như thế nào? (Phần 2)".

- "Đại Nam 3 lần đánh bại Xiêm La như thế nào? (Phần 3)".

Further reading

- Economic Equality and Victory in War: An Empirical Investigation

- 1825–1849

- Trần Trọng Kim, Việt Nam sử lược, Nxb Tân Việt, Sài Gòn, 1964

- Sơn Nam, Lịch sử An Giang, NXB Tổng hợp An Giang, 1988.

- Sơn Nam, Lịch sử khẩn hoang Miền Nam. Nxb Văn nghệ TP. HCM, 1994.

- Phạm Văn Sơn, Việt sử tân biên, Quyển 4. Tủ sách Sử học Việt Nam, sài Gòn, 1961.

- Hoàng Văn Lân & Ngô Thị Chính, Lịch sử Việt Nam (1858– cuối XIX), Q. 3, Tập 2. Nxb Giáo dục, 1979.

- Phạm Việt Trung – Nguyễn Xuân Kỳ – Đỗ Văn Nhung, Lịch sử Campuchia. Nxb Đại học và Trung học chuyên nghiệp, 1981.

- Liêm, Vũ Đức (2017). "Vietnam at the Khmer Frontier: Boundary Politics, 1802–1847". Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review. 5 (2): 534–564. doi:10.1353/ach.2016.0018. Retrieved 14 February 2019.